I’ve never been one to jump on bandwagons of trendy phrases and slogans. I’m not going to start now. I don’t care if they emanate from political Left field or political Right field. I avoid them all. Instead, I think it’s important to explain matters cogently and with the proper context, tossing aside phrases that create certain images in people’s minds that may not be accurate.

As much as possible, I always want to provide both theological and historical context for my explanations. There are three current phrases greatly in need of those contexts: black lives matter; institutional racism; and white privilege.

Let’s begin with “black lives matter.” Theologically, there is no legitimate question as to whether black lives matter. They do. When the apostle Paul spoke to the Athenians—his sermon on Mars Hill—he declared that “from one man He [God] made every nation of men” and “God intended that they would seek Him and perhaps reach out for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each one of us.” No distinction among ethnicities is raised here. We all are descended from the same original parents and all are made in the image of God.

Perhaps the most well-known Bible verse, even by those who have little familiarity with the Scriptures, is John 3:16, in which Jesus states very clearly, “For God so loved the world that He gave His one and only Son, that everyone who believes in Him shall not perish but have eternal life.”

Everyone means everyone.

Paul again, in Colossians 3: “Here there is no Greek or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, or free, but Christ is all and is in all.”

We see this in practice in the case of the Ethiopian in the eighth chapter of Acts. Philip, who had been one of the leaders in the Jerusalem church, was told specifically by an angel to travel on a certain road. As he obeyed, he came across an Ethiopian court official who was in charge of the Ethiopian queen’s treasury. He had been in Jerusalem to worship and was sitting in his chariot reading the book of Isaiah, the famous fifty-third chapter that so tellingly predicts Christ’s suffering. Philip is able to explain the meaning of the passage and what Christ’s death and resurrection meant. When the Ethiopian spies a body of water, he asks to be baptized. The Scripture then says he went on his way rejoicing.

The Gospel is for everyone. Therefore, everyone is equal in the sight of God. All are welcome into His family. And if God welcomes everyone, so should we. Black lives matter just as much as all other lives.

However, there is an organization that uses the name Black Lives Matter (BLM), and its underlying beliefs are troublesome from my Christian perspective. First, it is unabashedly pro-abortion. Yet abortion takes a higher percentage of black children than any other ethnic group. The percentage of blacks in America’s population would be much higher if abortion weren’t promoted in the inner-city areas. Don’t pre-born black lives matter?

The organization also promotes the LGBTQ movement and expresses animosity toward the concept of the traditional two-parent family (at least the one that comprises one man and one woman exclusively). Key leaders have praised Marxism and the movement is in the lead to defund the police.

For all of these reasons, I cannot support this organization, and if I simply reflexively parrot the phrase/slogan of “black lives matter,” might not some think I am on board with the beliefs of BLM?

I affirm that black lives do matter because the Scripture tells me that they do. That will be my foundation, not some radical organization that seeks to hijack Biblical truth with a substitute philosophy that is blatantly anti-Christian.

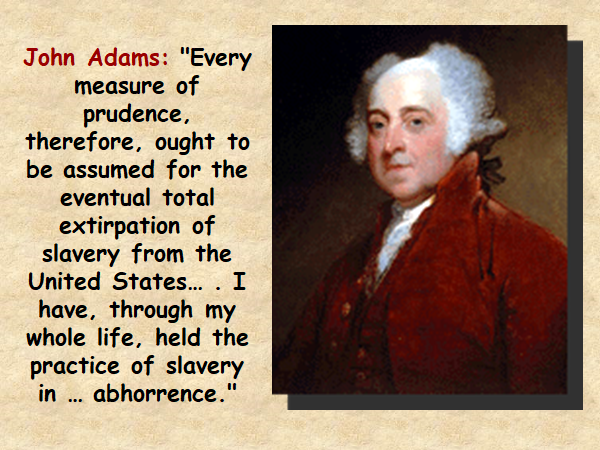

What about “institutional racism” and “white privilege”? Yes, they have existed historically in America. Some want to place the beginning in 1619 and also declare that the American Revolution was carried out to protect slavery. I dealt with that interpretation in a previous post. If interested, check out the post for July 8. Summary: slavery began slowly in America and didn’t find fuller development until the eighteenth century, at which time many of the Founders were deeply troubled by its continued existence and sought ways to limit and/or eventually abolish it.

The federal Constitution left the door open for the eventual abolition of slavery, even allowing for stopping the influx of slaves into the country, a law that did pass Congress and took effect in 1808. Yet there is no mistaking that at the state level in the southern states, slavery was established by law. In other words, it was institutionalized on the basis of race. That was certainly institutional racism.

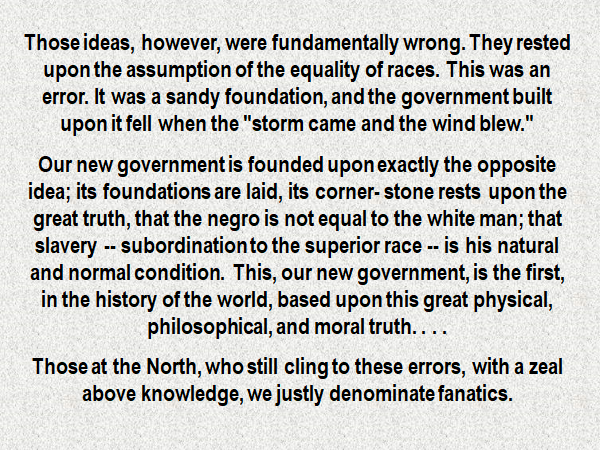

The dominant Southern view of slavery by the time of the Civil War can be found in Alexander Stephens’s “Cornerstone Speech” in March 1861. Stephens was the vice president of the Confederacy. He began his speech with a true statement: “The prevailing ideas entertained by him [Jefferson] and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically.” But then he continued,

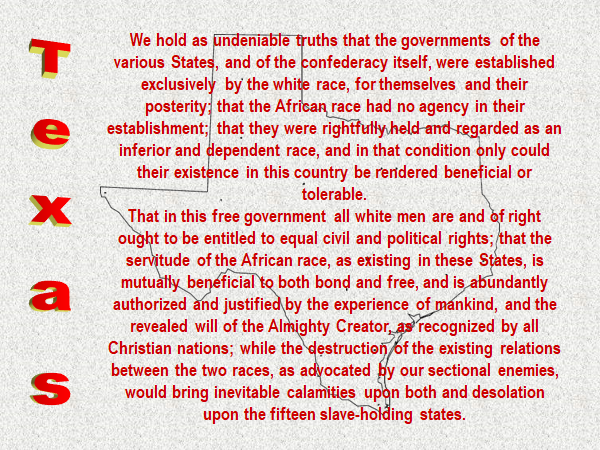

Can a clearer statement of institutional racism and white privilege be found anywhere? Well, perhaps this comment from the Texas secession declaration might be its rival:

It might be good to keep in mind, though, that the South lost that war. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, the 14th said that states could not abrogate basic rights of citizens, and the 15th said that the right to vote could not be denied “by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Institutional slavery was excised from the American body politic. The next phase, though, was legal segregation and the denial of much that was supposed to be protected by the 14th and 15th amendments. The apex of this sad development was the 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson that cemented separate-but-equal in law.

Therefore, it’s essential that we acknowledge institutional racism and white privilege in that decision and in the decades that followed.

Yet things can change. The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision by the Supreme Court upended Plessy v. Ferguson. That was followed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Government did what it could do to place all citizens on an equal plane legally.

We’ve also seen a black president elected twice, a black-Indian candidate for vice president in the current election cycle, and a multitude of black entrepreneurs, cultural icons, and political leaders rise up since the 1960s. One would think that might be enough to put to rest the “institutional racism” and “white privilege” slogans that are sprouting everywhere.

The reasons they are sprouting are many, but let me offer an opinion. The inner-city remains a place of poverty and despair for many. Why is that? Some of the blame can be placed on the good intentions of the 1960s Great Society program that has only increased over time. When government steps in to do more than it can reasonably (and constitutionally) do, there will be unintended consequences. Based on a philosophy that the system of capitalism is the culprit and that it has created systemic poverty, the government decided it could intervene to wipe out all poverty. It failed. Instead, with all the government funding for those in poverty, the unintended result was the decimation of the black family in the inner-city. Fathers weren’t as important as they used to be. Government was dad now. I hope the statistics have improved, but the ones I’ve seen show that more than 70% of black children raised in the inner-city do not have a father in the home.

Now, some will decry that analysis, but I believe that a stable two-parent family is one of the keys to lifting people out of poverty. Again, the statistics reveal that to be the case.

In a sense, we have institutionalized racism once again, albeit unintentionally.

There’s another aspect of this on which I will end this rather long post. The impetus now is to say that all white people are inherently racist. I couldn’t disagree more. My beliefs, grounded as they are on Biblical truth, don’t allow for racism. I welcome men and women of all ethnicities, knowing that we all are created in God’s image and are loved by Him. To be racist would be to deny that truth.

We are so fixated on color. I remember one person who famously held out this hope: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

How about we live out that hope? How about we stop judging people by the color of their skin and concentrate instead on the content of one’s character? This applies to black and white alike. If we do that, we will also be doing God’s will.