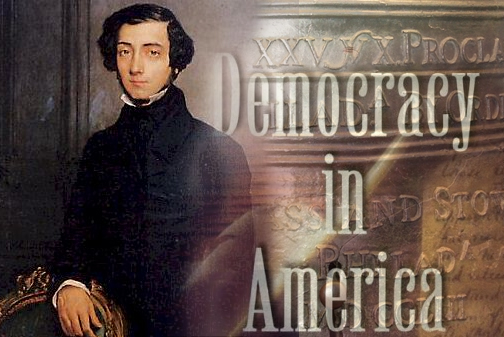

Alexis de Tocqueville, a Frenchman who toured America from 1831-1833, was a keen observer of what he experienced. He put those observations into a famous book, still used in political sciences courses, called Democracy in America, first published in 1835.

Tocqueville quotes can be found throughout the Internet; unfortunately, some of them dealing with religion in America are more legend than fact. I know, since I’ve read the entirety of his book without finding them. However, he did make clear statements about the influence of the Christian faith on American society. Here are some samples:

There is an innumerable multitude of sects [denominations] in the United States. All differ in the worship one must render to the Creator, but all agree on the duties of men toward one another. … All the sects … are within the great Christian unity, and the morality of Christianity is everywhere the same. …

… America is … still the place in the world where the Christian religion has most preserved genuine powers over souls; and nothing shows better how useful and natural to man it is in our day, since the country in which it exercises the greatest empire is at the same time the most enlightened and most free.

So this French observer was duly impressed with the unity he discovered among the various Christian denominations and the pervasiveness of the Christian faith in the nation. He also saw another practical effect of the universality of Christian faith: “Of the world’s countries, America is surely the one where the bond of marriage is most respected and where they have conceived the highest and most just idea of conjugal happiness.” Would that were the case today.

Christian influence on the morals of society dominated, according to Tocqueville:

Revolutionaries in America are obliged to profess openly a certain respect for the morality and equity of Christianity, which does not permit them to violate its laws easily when they are opposed to the execution of their [revolutionaries’] designs; and if they could raise themselves above their own scruples, they would still feel they were stopped by those of their partisans. Up to now, no one has been encountered in the United States who dared to advance the maxim that everything is permitted in the interest of society. An impious maxim—one that seems to have been invented in a century of freedom to legitimate all the tyrants to come.

So, therefore, at the same time that the law permits the American people to do everything, religion prevents them from conceiving everything and forbids them to dare everything.

Religion, which, among Americans, never mixes directly in the government of society, should therefore be considered as the first of their political institutions; for if it does not give them the taste for freedom, it singularly facilitates their use of it.

Tocqueville’s experience in France had taught him that religion combines with the state to produce tyranny. He was amazed to find the opposite in America:

On my arrival in the United States it was the religious aspect of the country that first struck my eye. As I prolonged my stay, I perceived the great political consequences that flowed from these new facts.

Among us [in France], I had seen the spirit of religion and the spirit of freedom almost always move in contrary directions. Here I found them united intimately with one another: they reigned together on the same soil.

What we have here is a nineteenth-century Frenchman with a sharper vision of the greatness and uniqueness of America than most current commentators, particularly those on the Left of the political spectrum. If only they would listen and learn from him.