Last week, I looked at the Roger Williams episode in early Puritan history and came to the conclusion that the Puritan establishment had good reasons to worry about his influence, given their desire not to have their charter taken away.

Today, let’s move on to the second major controversy to arise in Massachusetts in the 1630s. It had to do with a movement that historians call “antinomianism.” That’s just a fancy name for people who believe there is no law. It refers to both theology and the civil government.

This controversy didn’t begin with Anne Hutchinson—there were many others involved and questioned also—but her case seems to have come to the forefront, especially in our day when feminists are looking for a cause everywhere. They try to say that Hutchinson was bucking the “good-old-boy” system of Massachusetts. The historical record, though, doesn’t support that claim.

This controversy didn’t begin with Anne Hutchinson—there were many others involved and questioned also—but her case seems to have come to the forefront, especially in our day when feminists are looking for a cause everywhere. They try to say that Hutchinson was bucking the “good-old-boy” system of Massachusetts. The historical record, though, doesn’t support that claim.

Here are the essentials of what happened:

- First, Anne Hutchinson and her husband were part of a band of followers of the minister John Cotton, and when he removed to the New World, so did they.

- She began to claim that Cotton was the only preacher preaching the true Gospel, and that all others were preaching a gospel of works. Cotton, as a result, had to defend himself against being associated with her.

- What did she mean by a gospel of works? She said the ministers were wrong in telling people to prepare themselves for conversion through self-examination and a heart of repentance. What’s wrong with that? Well, even though the official theology of the Puritans was Calvinist, and predicated on predestination (it’s up to God who has been called and not the choice of man), they still believed one should prepare oneself in case God decided to choose you. Hutchinson said that was trying to work one’s way to heaven. In one sense, she was more consistent logically with Calvinism than the Calvinist ministers.

- That charge, however, got her into trouble because she was essentially saying all the ministers were leading people astray, and that since God was the ultimate decider of one’s salvation, one couldn’t look at a person’s life and determine if that person was saved or not. If a person’s outward life looked pious, that was no indication of salvation; a person who looked less pious might be the one God has chosen. That was one basis for the charge that she taught there was no “law,” i.e., any regard for outward actions.

- Then, they claimed she also made that application to society as a whole, teaching that true believers (the chosen) are taught directly by the Spirit of God and no civil or ecclesiastical authority could tell them what to do.

- Added to all this was the fact that she was holding meetings in her home to spread these ideas, and those meetings were being well attended, even by men. Puritans didn’t believe a woman should be teaching doctrine to men. This is the thin thread feminists use to say she was persecuted for being the first feminist. Yet that was only the proverbial tip of the iceberg for her accusers. The accusations were more foundational than that.

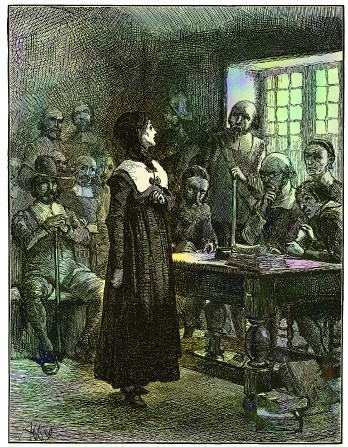

Hutchinson was put on trial and questioned on her views because they threatened to undermine the very basis of ecclesiastical authority and the need for civil government. By all accounts, she acquitted herself well since she had a sharp mind and ability to communicate effectively. Up until the end of this trial, she fended off their questions and seemed to have defended herself ably, never stepping over the line publicly about her beliefs.

Just when it seemed she would get off without a guilty verdict, she blew it. Apparently too flush with her “victory,” she began to regale the accusers with a special revelation she received from God in which He told her that they would fall under His judgment for their actions against her.

That was the step too far. Puritans were wary of anyone saying he or she had received any kind of special revelation, and when that revelation included a condemnation of the judges themselves, they reacted by pronouncing her guilty. The sentence was banishment, the same sentence pronounced on Roger Williams.

Hutchinson and her family moved first to Rhode Island, then down to New York, where a few years later, they were killed in an Indian attack. Her death, the Puritan magistrates concluded, was confirmation of their verdict. God had judged her.

So was Anne Hutchinson a heroine, standing up for women’s rights? There’s really no evidence of that. Was she a martyr, persecuted by evil men? That depends on whether you agree with her beliefs. If she was off the charts theologically [which is where I place her], then she was prosecuted for causing disturbances in the community and attempting to destroy the entire concept of authority in society.

So was Anne Hutchinson a heroine, standing up for women’s rights? There’s really no evidence of that. Was she a martyr, persecuted by evil men? That depends on whether you agree with her beliefs. If she was off the charts theologically [which is where I place her], then she was prosecuted for causing disturbances in the community and attempting to destroy the entire concept of authority in society.

The judges, though, have their share of pride in this. They didn’t like being told the theology their ministers were preaching was wrong. From my perspective and my understanding of Scripture, both sides held incorrect views.

Bottom line: this was a lose-lose situation. Neither side comes out looking all that good. Yet this was nothing compared to what happened when Quakers started showing up in Massachusetts in the 1650s. That’s where we’ll go next.