Last year’s major teaching project was the Ransom Trilogy. I’m now embarking on another one for the coming fall semester for my church’s Parish Academy program. I have no title for it yet, but the substance is set: an examination of key authors in C. S. Lewis’s life and circle. They are George MacDonald, G. K. Chesterton, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Dorothy L. Sayers. Lewis knew two of these writers by their works only; the other two he knew personally. But they all made a major impact on his understanding of the Christian faith.

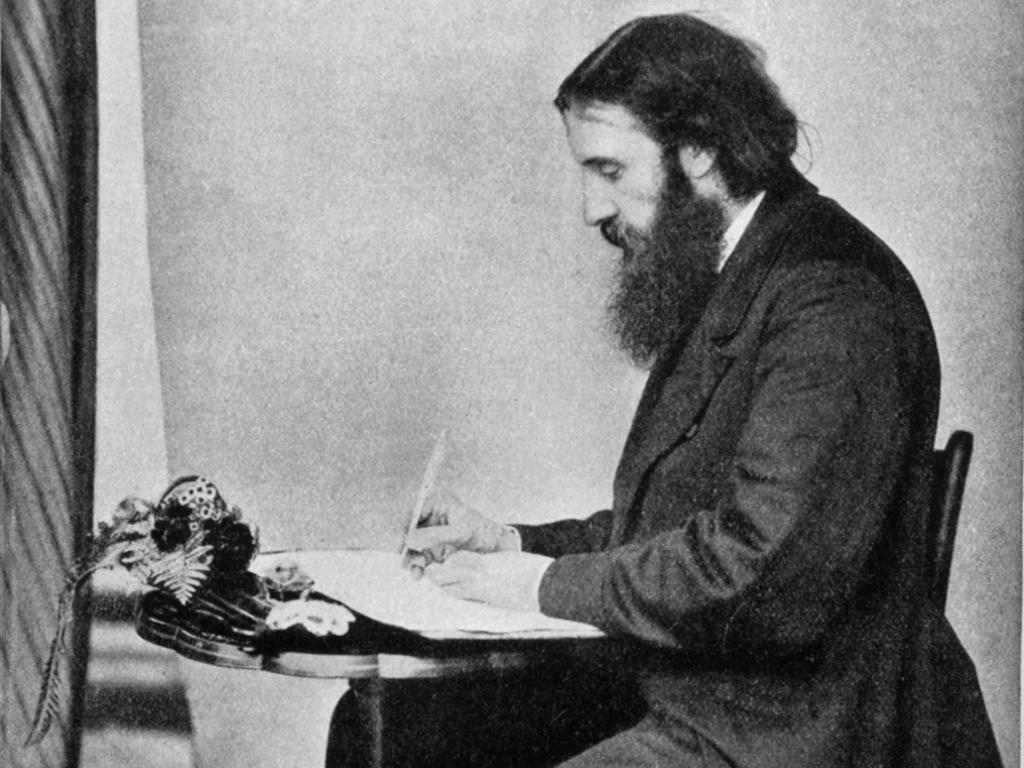

We are introduced to George MacDonald in Lewis’s autobiography, Surprised by Joy. In it, he recounts picking up MacDonald’s fantasy Phantastes at a railway station when he was a teenager studying under his tutor, William Kirkpatrick. The novel fascinated Lewis to the point that he declared it had baptized his imagination.

Later, in The Great Divorce, Lewis brought the resurrected spirit of MacDonald into the story as his guide and instructor while his character roamed around the outskirts of heaven. Of this mentor, Lewis states, “I dare not say that he is never in error; but to speak plainly I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself.”

That estimate of MacDonald’s spirituality comes from the preface Lewis wrote for a book he edited, George MacDonald: An Anthology, 365 Readings. Suffice to say that even though Lewis never had the opportunity to meet the author who died when Lewis was still a boy, MacDonald’s influence remained constant throughout Lewis’s life.

G. K. Chesterton was a contemporary with Lewis’s early years, but died in 1936 before Lewis’s fame as a Christian author. I am unaware of any direct meeting between the two, but Chesterton’s mind certainly connected with Lewis’s.

As with MacDonald, it’s in Surprised by Joy where we find Lewis’s commentary on the impact of Chesterton on his thinking. While serving in WWI, Lewis first read some of Chesterton’s essays. He didn’t know who Chesterton was or what he stood for, but he instantly knew he had found a mind to be reckoned with and not really sure “why he made such an immediate conquest of me. It might have been expected that my pessimism, my atheism, and my hatred of sentiment would have made him to me the least congenial of all authors.” Yet the young Lewis had come to a type of maturity in his reading, noting that one could “distinguish liking from agreement.”

Later, upon reading Chesterton’s Everlasting Man, Lewis felt like he received, for the first time, “the whole Christian outline of history set out in a form that seemed to me to make sense.” An oft-quoted paragraph from his autobiography is worth repeating here:

In reading Chesterton, as in reading MacDonald, I did not know what I was letting myself in for. A young man who wishes to remain a sound Atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere—“Bibles laid open, millions of surprises,” as Herbert says, “fine nets and stratagems.” God is, if I may say it, very unscrupulous.

Many of Lewis’s most poignant quotes have a basis in what he learned from Chesterton.

The relationship between Lewis and Tolkien is the most widely known, even among casual readers of the pair. They met at Oxford and bonded over language. Then, as the relationship developed, it was Tolkien’s explanation of myth that led Lewis to understand that in Christ the “true myth” had finally been realized in history.

They were the heart of the Inklings group in the 1930s and 1940s, and today, whenever anyone mentions the Inklings, those are the two names that come most readily to mind. The challenge they made to each other to write the kinds of books they wished others would write led to Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet. When Tolkien seemed to take forever to finish The Lord of the Rings, Lewis was the primary prompter to keep him on track and the most enthusiastic of reviewers of the completed work. Tolkien also was a key figure in ensuring that Lewis was offered, and accepted, the Chair of Medieval and Renaissance English Literature at Cambridge in the 1950s.

The challenge for me as I prepare this course is to go beyond The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in my personal knowledge of Tolkien’s works. I’ve already begun that quest.

The final author I will be highlighting is Dorothy L. Sayers, whom Lewis began corresponding with in the early 1940s, a correspondence that was lively and witty, and which led to a number of personal meetings in Oxford where she also had matriculated a few years before Lewis. While the general public first became aware of Sayers through her Lord Peter Wimsey detective novels, Lewis’s contact with her occurred at a period in her life when she turned away from writing detective stories and was establishing herself as a deep Christian thinker.

Her The Mind of the Maker, written before she met Lewis, received a positive review from him; he even referred to it in his testimonial to her life at her funeral in 1957. He was so delighted with her series of radio plays on the life of Jesus—The Man Born to Be King—that he made it an annual commitment to read them all during Lent each year afterwards. Finally, when she devoted the last decade of her life to a new translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy, Lewis was one of her staunchest supporters. Along the way, Sayers wrote a number of particularly bracing essays on Christian faith and practice that have led me to admire her facility with words. Lewis recognized that as well.

So that’s the plan. I’ve begun reading more about MacDonald, have read two additional Chesterton novels, am already enmeshed in Tolkien short stories, and am ready to revisit all that Sayers wrote. I’m hoping this course will be a great benefit to my adult students at the church, and that they will be drawn closer to the Lord just by being in such a course.