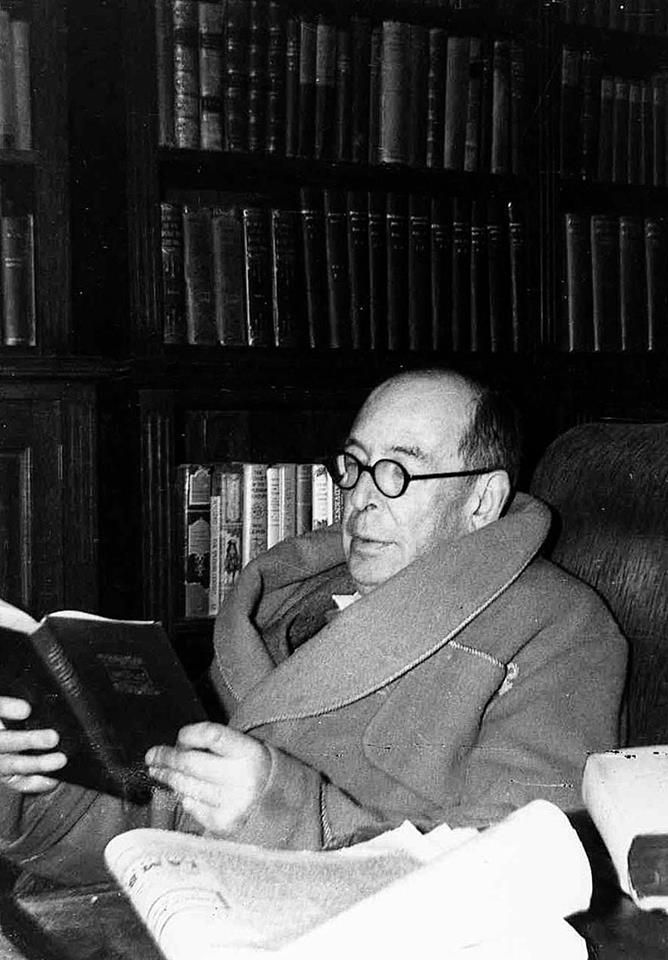

Fifty-six years ago yesterday, C. S. Lewis changed his place of residence. He left this vale of tears for the eternal home he had always longed for and which he wrote about so eloquently, particularly in The Great Divorce and in his sermon, “The Weight of Glory.”

He had fallen into a coma in July of 1963 and everyone thought those were to be his final moments. He surprised them by waking up and asking for some tea. He hadn’t even known he had been in a coma. When informed of it shortly afterward by Walter Hooper, Lewis mused on the fact that he was so near the heavenly gates but had to come back. He thought of Lazarus, who died and was resurrected, only to have to go through another death. Lewis indicated he would have preferred to have gained admittance into God’s presence at that time rather than having to return. Yet he submitted to the will of God, realizing that He is the one who will decide when our graduation day occurs.

In my book, America Discovers C. S. Lewis, I share some of Lewis’s correspondence with Mary Willis Shelburne, an American woman who had a fear of death. Lewis did his best to help Shelburne face her own demise with the proper Christian spirit and perspective. His letters become peppered with reminders that all humans have to face this ultimate test, but that Christians have a glorious eternity awaiting them. He joked about imminent death in a 1957 letter thusly: “What on earth is the trouble about there being a rumour of my death? There’s nothing discreditable in dying: I’ve known the most respectable people do it!”

Commenting in another letter on horrible visits to the dentist, he told her to keep in mind they both had to recognize that “as we grow older, we become like old cars—more and more repairs and replacements are necessary. We must just look forward to the fine new machines (latest Resurrection model) which are waiting for us, we hope, in the Divine garage!” And why not have the same attitude as the apostle Paul? “If we really believe what we say we believe—if we really think that home is elsewhere and that this life is a ‘wandering to find home,’ why should we not look forward to the arrival.”

In his final year, Lewis’s comments on death appeared more frequently, as he sensed his time was near. In March 1963, he conveyed to Shelburne his lack of concern about moving from this world to the next. A letter in June remarked on her obvious fear of dying; Lewis’s response was the most direct one yet: “Can you not see death as the friend and deliverer? It means stripping off that body which is tormenting you: like taking off a hair-shirt or getting out of a dungeon. What is there to be afraid of? Has this world been so kind to you that you should leave it with regret? There are better things ahead than any we leave behind.”

Lewis’s final word to Shelburne on the subject of death came three days later, about two weeks before he fell into a brief coma, followed by his resignation from Cambridge and his death four months after that. This final word showcases once again his facility with phrases that are memorable, as he encouraged her one more time: “I think the best way to cope with the mental debility and total inertia is to submit to it entirely. . . . Pretend you are a dormouse or even a turnip. . . . Think of yourself just as a seed patiently waiting in the earth: waiting to come up a flower in the Gardener’s good time, up into the real world, the real waking. . . . We are here in the land of dreams. But cock-crow is coming. It is nearer now than when I began this letter.”

That’s true for each one of us. I want to have Lewis’s perspective, that I am merely a seed waiting to be revealed as a flower in the real world, “the real waking.” But I need to be patient and wait for the Gardener’s good time.