The year 1776 is auspicious for the United States because that’s when we became the United States. Most of our attention in commemorating that event centers on the Declaration of Independence, and rightly so. I’ll have something to say about that document in a post next month.

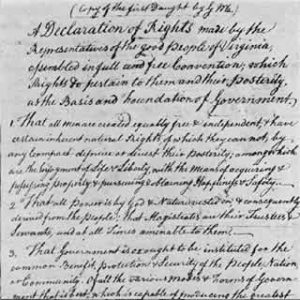

Another document, which was at Thomas Jefferson’s elbow when writing the Declaration, came out of his home state of Virginia a month earlier, but far too many of our citizens are ignorant of it.

George Mason, along with other key leaders in Virginia who were fashioning the new government there in anticipation of independence, created the Virginia Declaration of Rights as a bold statement of the limits of civil government.

George Mason, along with other key leaders in Virginia who were fashioning the new government there in anticipation of independence, created the Virginia Declaration of Rights as a bold statement of the limits of civil government.

This Declaration made clear the following concepts:

- Inherent rights (meaning those given by God) cannot be surrendered to the government.

- Government derives its power from the people, who set its limits.

- Oppressive government may be altered or abolished.

- The branches of government must be separated to avoid tyranny.

- The society operates on due process of law.

- There will be no excessive bail or fines and no cruel or unusual punishments meted out by government (wording later to be included in the Bill of Rights in the Constitution).

- No general search warrants were to be allowed (there must be specific cause for a search—anything else is an invasion of a person’s property).

- Freedom of the press should not be restrained.

- A militia of the people is a guarantor of liberty.

Sections 15 and 16 of this Declaration are worth quoting in full. Principles and character are the subject of section 15:

Sections 15 and 16 of this Declaration are worth quoting in full. Principles and character are the subject of section 15:

That no free government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people, but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue, and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.

Notice how the Founding generation focused on the significance of the character of its citizens. The consensus at the time was that a free government would fail without fundamental principles and without a people willing to exhibit those key character traits mentioned in the document.

Then there is section 16:

That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.

This is a clarion call for recognizing that civil government cannot dictate what an individual is required to believe. That’s between each individual and God. We should be free to follow our consciences. This statement comes fifteen years before the same concept was applied nationally in the First Amendment to the Constitution.

Another interesting aspect of this section is how it ends: it calls for Christian forbearance, love, and charity for all. The inclusion of the word “Christian” is another testimony to the consensus of the era. The Founders saw Christian faith as the bedrock of society even as they allowed everyone to have their own liberty of conscience.

In my view, Biblical principles are the foundation of everything that is good in the governmental institutions established in America. That’s why I labor to reintroduce them to this current generation. Ignorance of that fact and rejection of those principles are the reasons we are witnessing the slow decay of our culture and the various dysfunctions of our governments.