Joy Davidman Lewis, American wife of C. S. Lewis for the last few years of her short life, has been a subject of both great interest and great controversy for those who love Lewis and his writings. Born a New York Jew, Joy early decided she was an atheist and then completed that portion of her journey as a committed communist. She was fairly well known as a poet in her own right, particularly in the circles in which she ran.

Joy Davidman Lewis, American wife of C. S. Lewis for the last few years of her short life, has been a subject of both great interest and great controversy for those who love Lewis and his writings. Born a New York Jew, Joy early decided she was an atheist and then completed that portion of her journey as a committed communist. She was fairly well known as a poet in her own right, particularly in the circles in which she ran.

Only after a troubling marriage and the birth of two boys did she begin to question her communism and atheism, and Lewis’s works were instrumental in her Christian conversion. Her marriage fell apart and she moved to Britain primarily to pursue a relationship with her favorite author.

During my year-long sabbatical, as I researched for my book on Lewis’s influence on Americans (still in search of a publisher, for those interested), I read a lot by and about Joy—the short biography written by Lyle Dorsett, the newly released volume of her letters, and her only book written as a result of her conversion, Smoke on the Mountain.

Why was she so controversial? Many of Lewis’s friends were put off by her brashness and apparent arrogance. She also had a tendency to be rather judgmental of others, and her pursuit of Lewis came across as unseemly.

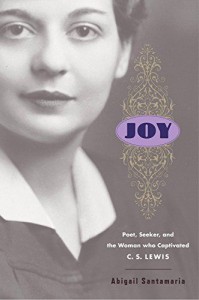

When I was attending the Lewis retreat last fall, I sat in on a breakout session with Abigail Santamaria, author of a new book titled Joy: Poet, Seeker, and the Woman Who Captivated C. S. Lewis. It was a most illuminating session as she talked about the struggles of her research and the conclusions she reached about the subject of that research.

When I was attending the Lewis retreat last fall, I sat in on a breakout session with Abigail Santamaria, author of a new book titled Joy: Poet, Seeker, and the Woman Who Captivated C. S. Lewis. It was a most illuminating session as she talked about the struggles of her research and the conclusions she reached about the subject of that research.

Santamaria wanted to find a true heroine, someone she could admire. Instead, she was disappointed by the woman she found who didn’t live up to her expectations. That didn’t mean there weren’t positives about Joy, but Santamaria admitted to some disillusionment as her research progressed.

Her book provides the most complete picture of Joy Lewis ever put into print—the good, the bad, and, yes, sometimes the ugly. I will acknowledge that as I was reading Joy’s letters last year, I also found myself at times wondering if a real conversion had actually taken place, as she was sometimes rather harsh on others. Yet C. S. Lewis knew her better than I, and I doubt he could have been “captivated” by anyone less than Christian.

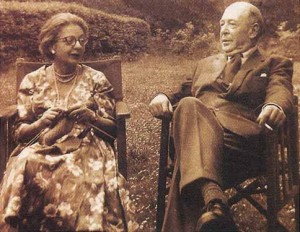

During the question-and-answer session after Santamaria’s presentation, I asked her why Lewis would have been drawn to someone like Joy. She answered without hesitation—he liked someone with whom he could spar intellectually, who would challenge him and test his own arguments and thinking. Lewis scholars acknowledge that Joy was practically his co-author for his novel Till We Have Faces, and that without her influence on his life, another book, The Four Loves, would not have attained the depth it has.

During the question-and-answer session after Santamaria’s presentation, I asked her why Lewis would have been drawn to someone like Joy. She answered without hesitation—he liked someone with whom he could spar intellectually, who would challenge him and test his own arguments and thinking. Lewis scholars acknowledge that Joy was practically his co-author for his novel Till We Have Faces, and that without her influence on his life, another book, The Four Loves, would not have attained the depth it has.

Santamaria also read a portion of her introduction to those of us in attendance. She told of how she had been given a wealth of heretofore unknown primary materials in Joy’s handwriting that she had to pore through. One night she couldn’t sleep. She writes, “The heat had stopped working, and I shivered under my blankets, tossing and turning for hours.”

Santamaria also read a portion of her introduction to those of us in attendance. She told of how she had been given a wealth of heretofore unknown primary materials in Joy’s handwriting that she had to pore through. One night she couldn’t sleep. She writes, “The heat had stopped working, and I shivered under my blankets, tossing and turning for hours.”

She gave up trying to sleep and started to look at some of the materials.

And then, huddled under my blankets, I came across a prediction Joy made: “I have wrenched sonnets out of great pain . . . / For unknown followers to find . . . / Some woman who is cold / In bed may use my words to keep her warm / Some future night, and so recall my name.”

Santamaria then writes, “I was no longer freezing, but I shivered.” A providential find? An assurance that God wanted her to complete this work? She concludes,

I had not set out to unearth the particular realities I discovered behind the Shadowlands tale; they were imparted to me, first in the memories of those I interviewed, and finally in Joy’s own words. She left them to be found: she was giving me her blessing.

Santamaria’s book is one of those that is hard to put down if you have an avid interest in Lewis and his life. She writes well, tells a good story, and offers a narrative that flows. It’s clearly the most comprehensive treatment of the life of Joy Davidman Lewis that exists. Interest in Lewis has not ebbed after all these years; Abigail Santamaria’s Joy is a substantive addition to Lewis scholarship.