We’re talking about Puritans in our ongoing trek through American history in this blog. As I mentioned in last week’s post about them, there is this stereotype that is difficult to reverse. But I hope I showed that not only were they earnest in their faith, but that they understood the concept of a covenant with God in which they needed to love one another.

Were the Puritans always faithful to that covenant? Did they always treat each other in the Christian way? Well, I promise to get to that in my next history post, but today I want to emphasize something else that doesn’t quite fit the stereotype—their ideas of government and rights.

The Puritans who came to Massachusetts under the authority of the Massachusetts Bay Company did something unique with respect to colonies. Rather than have a board of directors 3000 miles away in England, this company’s directors pulled up stakes and became part of the settlement. This allowed greater knowledge of the needs of the colony and, as an added bonus, removed the stern oversight they would have received from the Anglican establishment that had kept all zealous Puritans from positions of influence.

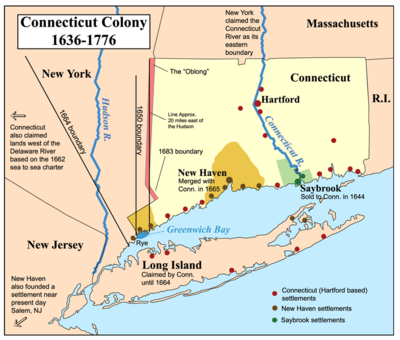

We also see a couple of governmental firsts in the New World with their arrival. One group, led by Rev. Thomas Hooker, departed from Massachusetts on good terms to settle on land further south. This was the beginning of what became the colony of Connecticut.

Based upon the principles in a sermon Hooker preached, these people decided to write a formal constitution to set up rules for the colony’s governing. This document, called The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, written in 1639, makes it clear that God is the one who desires stable government. It then goes on to outline how that government is to function. For all practical purposes, this is the first American Constitution. Historian Paul Johnson even refers to it as the first real constitution of its kind in the world.

One feature in these Fundamental Orders that I find especially telling is the comment that if a situation arises where no law has already been created to deal with it, the government should resort to the Word of God for a decision on what to do. You can’t be more Biblically based than that.

Another key governmental document from this period stems from Massachusetts in 1641. Concern over possible governmental intrusion into areas where civil government doesn’t belong led to the passing of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties. Written by Rev. Nathaniel Ward, this document guaranteed certain rights that the government couldn’t violate. Among those rights were the following:

Another key governmental document from this period stems from Massachusetts in 1641. Concern over possible governmental intrusion into areas where civil government doesn’t belong led to the passing of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties. Written by Rev. Nathaniel Ward, this document guaranteed certain rights that the government couldn’t violate. Among those rights were the following:

- One’s life, liberty, and property were to be secure from arbitrary actions of the government

- Citizens of the colony had the freedom to disagree with the government without penalty; they could petition for a redress of grievances

- No double jeopardy would be allowed—in other words, one could not be brought up on the same charges again and again without new evidence

- There were to be no cruel or excessive punishments; the punishment had to fit the level of the crime

- No self-incrimination under torture

- A death sentence required the testimony of two or three witnesses

- Special dispensation was given to children, mental incompetents, and newcomers to the colony; this shows they differentiated on how people were held accountable to the laws

- No slavery was allowed, except for enemy soldiers captured in a just war

Many of these ideas predated the famous English Bill of Rights of 1689. The Massachusetts Body of Liberties was, in effect, the first American bill of rights.

So it was those supposed narrowminded Puritans who gave us our first constitution and bill of rights. Not bad for a people who are largely criticized today. Does that mean that they didn’t have their controversies, mistaken notions, and bad decisions? Of course not. We’ll examine some of those next time.