When I was working on my master’s and doctoral degrees in history, I distinctly recall an attitude that some of my professors had toward the American colonial and revolutionary eras—they conveyed to us, their students, the idea that the leaders of those eras were just so backward when compared to the more enlightened age we live in now. I didn’t accept that attitude then; I don’t accept it now.

Yes, we have progressed technologically in ways our Founders would find astonishing. Technology, though, is hardly a substitute for principle. Neither can we be considered more advanced if we have dismissed the Biblical framework that gives us a proper understanding of the place of man in God’s creation. That Biblical framework offers us, as well, a greater comprehension of the role civil government should play in the overall society. Personally, I believe a lot of those early Americans have a lot to teach us still.

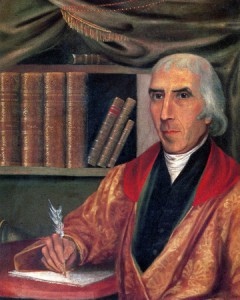

When I was writing my master’s thesis, I researched the lives and writings of two prominent Americans of the Founding Era: Timothy Dwight and Jedidiah Morse. Most people today have no idea who they were. Dwight served ably for many years as president of Yale, ensuring it retained its Christian foundations. Morse, a pastor, also was famous as the Father of American Geography; he wrote the first American textbook on the subject, which was the first to include key geographical features of North America. His fame was eventually superseded by that of his son, Samuel F. B. Morse, who invented the telegraph.

Jedidiah Morse gave a sermon in 1799 that includes one of the best quotes I’ve ever read on the relationship of Christianity and civil government. A lot of quotes from this era, both genuine and spurious, have made their way to the internet, but I’ve never seen this one make the rounds. I’d like to offer it now for your consideration. Here’s what Morse would have us remember:

Jedidiah Morse gave a sermon in 1799 that includes one of the best quotes I’ve ever read on the relationship of Christianity and civil government. A lot of quotes from this era, both genuine and spurious, have made their way to the internet, but I’ve never seen this one make the rounds. I’d like to offer it now for your consideration. Here’s what Morse would have us remember:

Our dangers are of two kinds, those which affect our religion, and those which affect our government. They are, however, so closely allied that they cannot, with propriety, be separated. The foundations which support the interests of Christianity, are also necessary to support a free and equal government like our own. . . .

To the kindly influence of Christianity we owe that degree of civil freedom, and political and social happiness which mankind now enjoy. In proportion as the genuine effects of Christianity are diminished in any nation, either through unbelief, or the corruption of its doctrines, or the neglect of its institutions; in the same proportion will the people of that nation recede from the blessings of genuine freedom, and approximate the miseries of complete despotism. . . .

Whenever the pillars of Christianity shall be overthrown, our present republican forms of government, and all the blessings which flow from them, must fall with them.

When I read those words, I am impressed by the wisdom behind them. Religious beliefs always provide the context of what a people accept as appropriate in society. Christianity, in particular, lends itself to genuine liberty. When Christianity recedes into the background, liberty recedes also. Morse’s words are a warning to a people who, in their pride, abandon Biblical principles and replace them with man-centered, humanistic ideas. If the blessings of our republican forms of government seem to be disappearing, we would do well to ponder what Morse says—the reason is that we are attempting to overthrow the “pillars of Christianity.”

We have a lot to learn from those who have preceded us. It’s not too late to take their warnings seriously and make a course correction. It will take humility on our part, however. Are we up to the challenge?