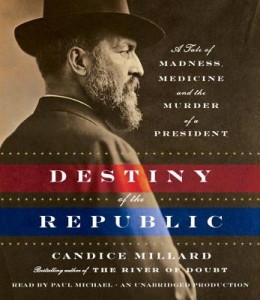

I love history books that read like novels. History is a story and should be told accordingly. Character, plot, and all other features of a good novel should be incorporated. As long as the story is fully documented and doesn’t deviate from the facts, it can be a delight to read. I just finished one such book. It’s called Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President by Candice Millard.

I love history books that read like novels. History is a story and should be told accordingly. Character, plot, and all other features of a good novel should be incorporated. As long as the story is fully documented and doesn’t deviate from the facts, it can be a delight to read. I just finished one such book. It’s called Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President by Candice Millard.

Few Americans know much about President James Garfield. Those who do only know that he was shot a mere four months after taking office and lingered for another two and half months before dying in September 1881. That’s the extent of our collective knowledge, if we know anything about it at all. As a historian, I had further details. For instance, I knew that Garfield was an evangelical Christian who was ordained through the Disciples of Christ. I also knew that he was a reformer in the best sense—not someone who believed that the federal government should take on responsibility that belongs to individuals, but a man who sought to remove the corruption of the spoils system. As president, in those four short months before the fateful day when he was shot, he already had taken bold steps in that direction.

This book, though, opened up a vista of new information about the man: his commitment to protecting the civil rights of former slaves; the deep relationship he developed with his wife; the high regard in which he was held even by political opponents because of his integrity and kindness. Upon finishing this book, I felt the pain of the loss of someone who could have been a good friend, if I had lived at that time.

The book also paints a portrait of Charles Guiteau, the assassin. All I ever heard was that he was a disappointed office-seeker, perhaps a little crazy. Both are true, but only scratch the surface of the madness a man can exhibit when he gives himself over to megalomania. At first, he was part of a commune that believed in “complex marriage.” He later tried to fashion an identity as a traveling evangelist, but most of his traveling was to stay one step ahead of those to whom he owed money.

The book also paints a portrait of Charles Guiteau, the assassin. All I ever heard was that he was a disappointed office-seeker, perhaps a little crazy. Both are true, but only scratch the surface of the madness a man can exhibit when he gives himself over to megalomania. At first, he was part of a commune that believed in “complex marriage.” He later tried to fashion an identity as a traveling evangelist, but most of his traveling was to stay one step ahead of those to whom he owed money.

After Garfield’s election, Guiteau believed he himself was responsible for the victory and that he was owed an ambassadorship to France. He was wildly out of touch with reality. He finally came to the conclusion that God wanted him to remove Garfield so that the vice president, Chester Arthur, would become president, which would pave the way for Guiteau to realize his dreams. He thought the American people would hail him as a hero. He was literally out of his mind.

The entire American public followed the drama of Garfield’s treatment, hoping that the man they admired would recover from his wounds. The greatest irony is that he would have recovered, if not for the proud, arrogant doctor who took charge of his care—a doctor who rejected the new theory of protecting against germs and infection. Garfield eventually succumbed due to the mistreatment he received at that doctor’s hands. Along the way, the author also gets us better acquainted with Alexander Graham Bell, who was called upon to try a new invention to find the bullet lodged in the president.

The story is tragic. Yet it is a story well told, one that will grip you as you quickly pass from chapter to chapter. Even though you know the ending, you keep hoping it won’t turn out the way it did. In short, this is a terrific read, one that you won’t soon forget.