We love to talk about heaven. Hell, not so much. We get glimpses of both eternal destinations in Scripture, but not the full picture of either. C. S. Lewis is well known for perceiving both in imaginative ways. On the subject of hell, we naturally think of The Screwtape Letters, where in his preface he tells us, “We must picture Hell as a state where everyone is perpetually concerned about his own dignity and advancement, where everyone has a grievance, and where everyone lives the deadly serious passions of envy, self-importance, and resentment.”

That description, of course, refers to the the fallen angels who have become devils. But what of men and women who end up in the infernal place? Do they exhibit the same traits?

In The Problem of Pain Lewis reminds us that it’s those very traits that are the reason people end up in hell. “Though Our Lord often speaks of Hell as a sentence inflicted by a tribunal, He also says elsewhere that the judgment consists in the very fact that men prefer darkness to light, and that not He, but His ‘word,’ judges men.” Lewis finishes this thought in this way:

We are therefore at liberty—since the two conceptions, in the long run, mean the same thing—to think of this bad man’s perdition not as a sentence imposed on him but as the mere fact of being what he is.

The characteristic of lost souls is “their rejection of everything that is not simply themselves.”

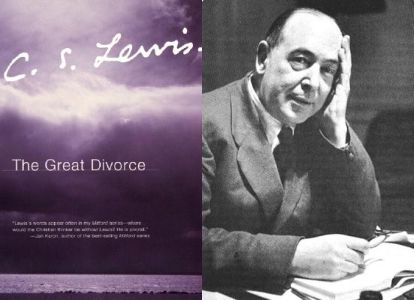

It’s in his masterful fantasy story The Great Divorce where Lewis best lays out the theme that our self-centeredness is the essence of our sins and the cause of our eternal damnation. The narrator, Lewis himself, has taken a bus from hell to the outskirts of heaven. Other passengers on this bus are given one last opportunity to exchange their hellish existence for a heavenly one. The Lewis character is astonished why anyone wouldn’t want to make that exchange. Lewis the author has inserted one of his favorite writers, George MacDonald, as Lewis the character’s guide in this heavenly realm. When Lewis inquires of MacDonald why anyone would choose hell, MacDonald replies,

“Milton was right,” said my Teacher. “The choice of every lost soul can be expressed in the words, ‘Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.’

There is always something they insist on keeping, even at the price of misery. There is always something they prefer to joy—that is, to reality. We see it easily enough in a spoiled child that would sooner miss its play and its supper than say it was sorry and be friends.”

There it is—self-centeredness as the essence of sin. Then comes perhaps the most-often quoted sentence in this book:

Lewis concludes, “All that are in Hell, choose it. Without that self-choice there could be no Hell. No soul that seriously and constantly desires joy will ever miss it. Those who seek find. To those who knock it is opened.”

So, yes, God does impose a sentence, but in the same manner as a human judge imposes a sentence on a criminal: the criminal has chosen to be a criminal and has earned it. All who go to Hell are merely extending their hellishness from this life to the next.

Yet notice how Lewis’s comment ends—with the words of Jesus who promised that He is always ready to open the door to His eternal life to all who choose that path. God’s promise is sure: He came to seek and to save those who are lost, if only they will acknowledge their lostness and desire Him instead. The doors to both eternal destinations are open to each of us. We make the choice as to which one we will enter.