I concluded my class, “C. S. Lewis on Life, Death, and Eternity,” this past Monday evening. In the previous session, we looked at Lewis’s poignant thoughts after the death of his wife, Joy, in A Grief Observed. As significant as that reading is—and it affects many people deeply—I didn’t want to end the class on that note. I preferred that we finish with a joyful glimpse into the essence of the Christian life and the hope of eternity.

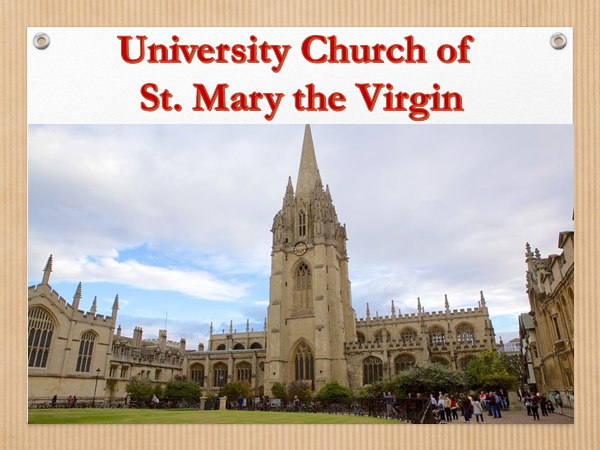

For that reason, I chose Lewis’s famous sermon, “The Weight of Glory,” delivered during the dark early days of WWII at the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Oxford.

Over twenty years ago, I climbed the stairs to nearly the top of that steeple and viewed Oxford from that height. On my last visit, in 2017, we got there a few minutes too late for that, but I did take a photo of the pulpit where Lewis delivered the sermon, which, in those twenty years between visits, had taken on greater meaning for me.

How I would have loved to have been in the congregation that day listening to Lewis (in his magnificent voice) bring such precious nuggets to those assembled. But at least we have the transcript, and it provides the heart and soul of the message for our generation. I’ve often noted how nearly everything Lewis wrote, regardless of how long ago he wrote it, nevertheless reaches out and communicates truth in a timeless fashion.

In my Monday session, I covered the entire sermon, but for the purposes of this post, I will concentrate on some of the best-known passages. Take this one, for instance:

We settle for so little, when the Lord wants to give us so much. We think the “joys” of this life will suffice, but they are like those mud pies in the slum. Everything God offers instead is like the holiday at the sea—and how can a mud pie ever compete with that?

Lewis speaks of how we seek beauty but try to find it in all the wrong places. We can be deceived by idols that have the trace of true beauty but are not the real thing itself.

This is poetry in prose, effectively leading us to break the enchantment of worldliness and realize that a real heaven awaits—a place of glory where those who have received God’s grace will finally understand what it means to be pleasing to God.

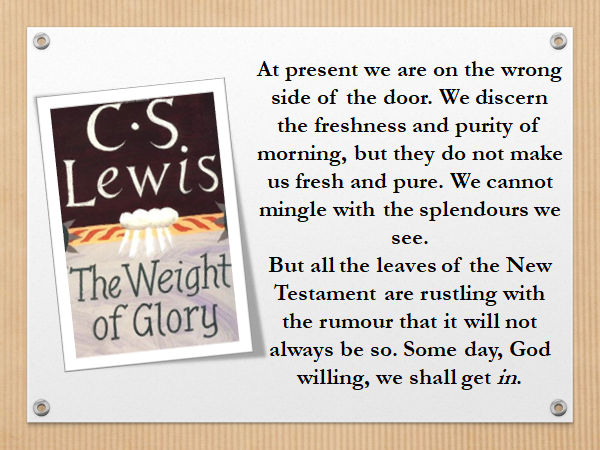

We don’t experience that glory yet because we remain bound to this earthly life. Yet it beckons to us. In The Last Battle, Lewis has the saved Narnians pass through a door that leads them into the New Narnia, the Eternal Narnia. He wrote that more than a decade after this sermon, but he had that image in his mind already.

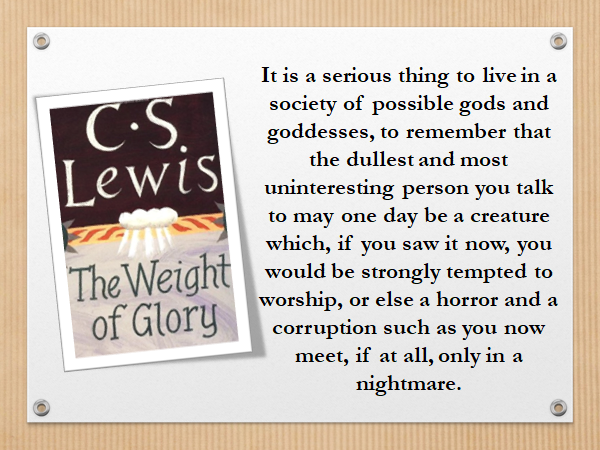

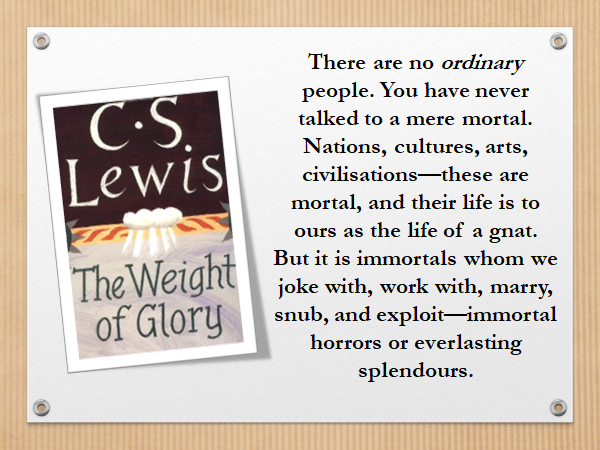

Meanwhile, since we haven’t yet passed through that door and we are not yet in, we must continue to deal with everyday life and all the people who cross our path. Lewis, therefore, as he closes the sermon, wants to help us see those people in a new light.

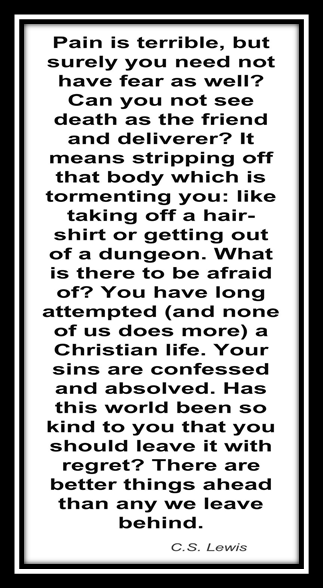

After Joy’s death in 1960, and the pain of A Grief Observed, Lewis’s faith in his Lord was undiminished. It was perhaps even stronger in the aftermath of his spiritual struggle. One of his American correspondents, Mary Willis Shelburne, wrote of her fear of death. Lewis responded, “As we grow older, we become like old cars—more and more repairs and replacements are necessary. We must just look forward to the fine new machines (latest Resurrection model) which are waiting for us, we hope, in the Divine garage.” In another letter to Shelburne, he urged her to get the right perspective:

Yes, there are better things ahead than any we leave behind. We will be on the right side of the door. The leaves of the New Testament are rustling with the rumor that we shall get in.