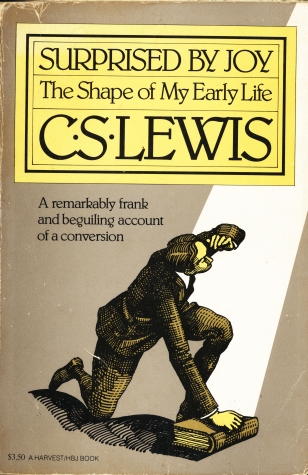

I have used C. S. Lewis’s autobiography, Surprised by Joy, every time I have taught my Lewis class at the university. I’ve also used it in an adult class at my church. The title perfectly expresses the end result of Lewis’s early life as he finally turned to Christ. For years, he sought something he defined as “joy.”

Three moments in his childhood stood out to him with respect to his quest for joy. The first was when he “stood beside a flowering currant bush on a summer day.” It reminded him of the time when his brother had brought his toy garden into the nursery. Both instances—the bush and the toy garden—gave him a sensation of deep desire. Yet just as he felt that desire, it had vanished.

The second glimpse of joy was when he read Squirrel Nutkin by Beatrix Potter. He was enamored by the “Idea of Autumn.” Again, he experienced a deep desire that quickly passed. He wanted to reawaken that feeling but failed to do so.

The third moment came upon him as he read Norse poetry. The words “I heard a voice that cried, Balder the beautiful is dead, is dead” captured his imagination. The sensation of northern sky—“cold, spacious, severe, pale, and remote”—overwhelmed him. Lewis then explains,

I will only underline the quality common to the three experiences; it is that of an unsatisfied desire which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction. I call it Joy which is here a technical term and must be sharply distinguished both from Happiness and Pleasure. Joy (in my sense) has indeed one characteristic, and one only, in common with them; the fact that anyone who has experienced it will want it again. Apart from that, and considered only in its quality, it might almost equally well be called a particular kind of unhappiness or grief. But then it is a kind we want. I doubt whether anyone who has tasted it would ever, if both were in his power, exchange it for all the pleasures in the world. But then Joy is never in our power and pleasure often is.

This is a familiar concept to those who are well acquainted with Lewis. So why do I take the time to repeat it? I do so because I recently finished reading Lewis’s diary from the 1920s.

I admit that I have had some reluctance to delve into this volume, All My Road Before Me, because I wasn’t as attracted to what Lewis thought pre-conversion. I was having such a wonderful time with all of his Christian writings. Why waste time with the thoughts of a young man who, as Lewis even described himself, was totally absorbed in himself and considered God (if He even existed) to be the great Interferer in his life. He looked upon the universe as “a rather regrettable institution” and sought to surround his own soul “with a barbed wire fence” along with a notice: “No Admittance.” He continued, “And that was what I wanted; some area, however small, of which I could say to all other beings, ‘This is my business and mine only.'”

With an attitude like that, perhaps you can see why I shied away from the diary. Yet as I plunged into it, I discovered not only a deeper understanding of Lewis in those early years, but also a running commentary throughout the diary of his ongoing quest to reawaken that sense of Joy.

Examples abound, and I will share the most pertinent. In June 1922, he wrote the following:

A very beautiful morning. I cycled into Oxford, leaving my bike in College: from there I walked through Christ Church down into Luke St., over the waterworks and up the fold in the hill from Hinksey to the top. Sat down in the patch of wood—all ferns and pines and the very driest sand and the landscape towards Wytham of an almost polished brightness. Got a whiff of the real joy, but only momentary.

Many of his experiences in which he got whiffs of joy were like this one. He would walk in nature, sit a while, and hope for the return of that “unsatisfied desire which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction.” And in each case, if it occurred at all, it would be fleeting.

Sometimes, Lewis would walk with a friend and hope for that “whiff.” On one occasion, in November of that same year, he captured it again. He and the friend went into a woods together where, he said, “we were as pleased as two children reveling in the beauty, the secrecy, and the thrill of trespassing. … I got the real joy in this wood.”

A year later, reflecting on a visit to his father in Ireland and having trouble sleeping, he embarked on many long walks to try to help him sleep at night. Of those walks, he noted, “The view down the chasm between Napoleon’s Head and the main body of the cliffs is almost the best I have seen. I had one other delightful walk over the Castlereigh hills where I got the real joy—the only time for many years that I have had it in Ireland.” That’s two occasions where he calls it “the real joy,” presumably not simply an artificial “high.” Then in March 1924, he related,

When I came out of the dark library (at about 4) the air was wonderfully bright and soft in colour. It was like a summer evening at six o’clock. The stone seemed softer everywhere, the birds were singing, the air was deliciously cold and rare. I got a sort of eerie unrest and dropped into the real joy. Never have I seen Oxford look better. It looked as it used to when I saw it in my cadet days and used to long for it to be a University town again. I took two or three turns up and down the Broad. Although it is only a few hours old I see that this is already becoming transfigured by memory into something that never was anywhere and never could have been.

In June 1924, on a walk with the family dog, Lewis went to his favorite “fir grove where I sat down for a long time and had the ‘joy’—or rather came just within sight of it but didn’t arrive.” What I see here is a Lewis who is analyzing his life through an emotional prism. He seeks that old feeling, but this time it doesn’t quite come and he is disappointed. Even when he does say that he finds the “real joy,” it never lasts and he eagerly seeks to experience it again.

A vacation in the west of England in September 1925 offered Lewis new scenery for his rambles, and he delighted in constant walks. After he traversed the moor, he had to scramble down a steep hill to enter “into thick and silent woods.”

Every kind of tree grows here, all at an acute angle on the steep hillside. There is plenty of moss and ivy and biggish rocks and boulders, some covered with green, some sticking through like bones of the hill. I sat there and again came very near the real joy, but did not quite arrive.

The joy Lewis sought was always elusive, and as he indicated in his autobiography, Joy is never in our power. In fact, he finally gave up trying to capture it because he eventually, through Christ, found what that Joy was connected to. The final words in Surprised by Joy make it clear that his quest was realized, but not in the manner he expected. That’s why he was surprised by what constituted the “real joy.” He came to the realization that Joy “was valuable only as a pointer to something other and outer. While the other was in doubt, the pointer naturally loomed large in my thoughts.” Then he ends the book with what I believe is an apt illustration.

When we are lost in the woods the sight of a signpost is a great matter. He who first sees it cries “Look!” The whole party gathers round and stares. But when we have found the road and are passing signposts every few miles, we shall not stop and stare. They will encourage us and we shall be grateful to the authority that set them up. But we shall not stop and stare, or not much; not on this road, though their pillars are of silver and their lettering of gold. “We would be at Jerusalem.”

The Joy he sought—that elusive thing—was merely a signpost letting him know the right road. The road leads to the New Jerusalem of Christian faith. Lewis found that road and never turned back.