Dorothy L. Sayers was a “find” for me in just the last few years. Once I realized she and C. S. Lewis were friends and that he loved her BBC radio plays titled The Man Born to Be King, I knew I had to be better acquainted with her writings. I read all of her Lord Peter Wimsey novels, luxuriated in The Mind of the Maker, devoted myself to the book version of the radio plays (with her marvelous introduction), and practically devoured her essays on the Christian creeds and the drama of salvation. While I would love to write a book about her, others, far more expert in explaining Sayers’s life and thought, have gone before me to prepare the way in case I ever get that opportunity.

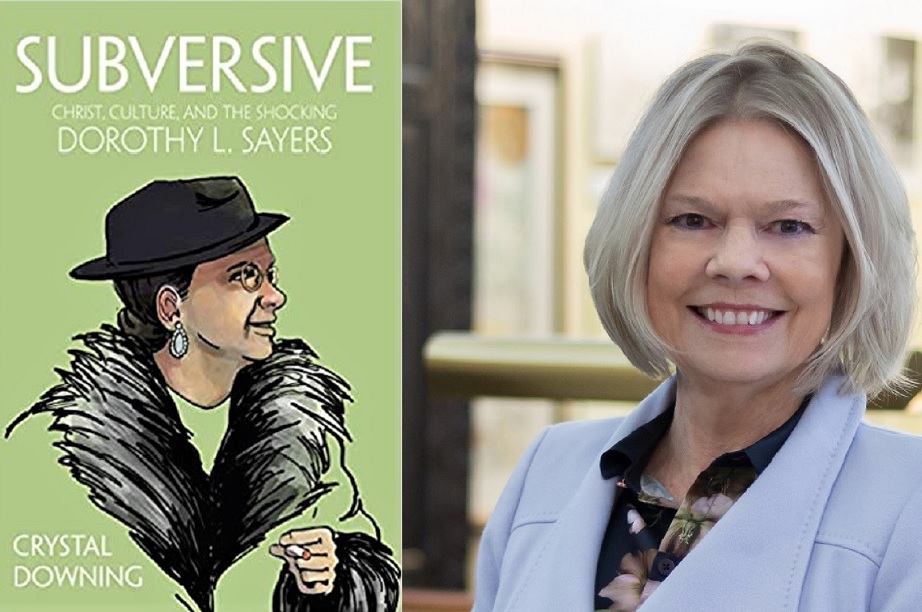

I would like to highlight one of those books today because I consider it a carefully crafted, cogently argued scholarly work that is also a joy to read. I offer my endorsement of Crystal Downing’s Subversive: Christ, Culture, and the Shocking Dorothy L. Sayers.

How does one write a review of a book that tempts one to recreate the entire book in the review? There are many layers to Downing’s portrait of her “subversive” subject. She has a long history of familiarity with Sayers’s works (including a previous book about her), and now, as co-director of the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College, she has everything connected to Sayers at her fingertips. She uses her resources admirably.

The use of the term subversive is attention-grabbing because one normally uses that word negatively—that’s the natural connotation. And then there’s that other word: shocking. When you put the two together, you immediately wonder how that could possibly apply to Sayers. Is Downing painting a dark portrait here? But of course every word must be understood in context. It depends what one wishes to subvert. Maybe there are some things in the way Christians understand things that ought to be upended. And shocking? Well, Christians throughout the ages have always been shocked when someone comes along and presents the Good News in a new way, a way that subverts “the way we’ve always done things.” That, says Downing, is what Dorothy Sayers excelled in doing, and her subversive tactics opened up a greater grasp of the Gospel to her generation.

When the introduction takes as its title “The Murder of God,” one can already see the intent: that’s not the way one usually talks about the crucifixion. It gives the reader a jolt right from the start, and it exemplifies one of Downing’s key themes: stop using words and phrases repeated so often that they are robbed of their meaning. Crucifixion means that God was killed by men. While we actually know that, the word itself has been drained of the impact it deserves. This is a dramatic story—the most dramatic story of all time.

When Sayers wrote The Man Born to Be King, she put it in the language (even some American slang, her critics said) of the people in her day. She gave the narrative a new life, a way of understanding what happened in the life of Jesus that made it real to the people listening. It’s okay to subvert old language that has numbed the soul; it’s acceptable to provide a shocking alternative.

Downing shares Sayers’s thought the first time she was introduced to an escalator in 1915. It was so new that “a friend held her arm, worried she might ‘get giddy.’ . . . Suddenly an old lady pushed violently past me . . . muttering ‘I must get down this thing quickly, I’m always sick if I don’t.'” The shock of the new subverted the old stairways. “Cultural innovations at their start,” says Downing, “often generate distress, making us feel as though safe ground is moving away too quickly. But over time we adjust, just as Christians adjusted to colloquial language in The Man Born to Be King.”

Yet those escalators need a firm foundation, without which they would be unsafe. Here is where Downing incorporates Sayers’s dedication to the only firm foundation the church has—Jesus Christ Himself. The new language doesn’t subvert the real message, only the way in which that message is delivered, thereby giving it a new force.

Beginning in chapter two, “Religious Shopping and Exchange,” Downing turns to a theme that weaves its way seamlessly throughout the rest of the book: the tendency for Christians to view the faith as a means of exchange rather than a personal relationship with the God of the universe.

God is not a Transcendent Boss that expects underlings to do certain tasks in order to earn their due reward. True love, in other words, renounces an economy of exchange. Even the most hardened atheist recognizes a lack of love in anyone who says, “I’ll love you only if you do something for me in exchange.” The God of Christianity renounces exchangism, preferring to be in relationship with all of creation, such that each and every human can be a “sharer” and “fellow worker” in that creation.

Sayers was alienated from Christian faith at an early age due to this exchange mentality. It made Christianity no different than other religions in its approach to the Deity. Years later, she was able to see more clearly that God was simply offering the “gift” of salvation that only needed to be accepted. This is why Sayers disdained the typical evangelical emphasis on emotionalism, dramatic conversions, forced evangelism, and a “bibliolatry” that shocked people when she abandoned King James English in The Man Born to Be King.

The exchangism inherent in the concept of purgatory in Luther’s time is what led him to “subvert” that doctrine and “shock” the church with a Reformation. Some traditions need purging, but only those that undermine the true faith of the early church councils and the creeds they produced, says Sayers. Downing, in summarizing Sayers’s views, explains, “Anytime we reduce Christian belief and practices to an economy of exchange we destabilize the distinctive essence of Christianity: the non-negotiable truth that salvation through the death and resurrection of Christ is a gift.”

Even the atonement of Christ on the Cross has become an exchange in most people’s theology, Sayers complained. In one of her essays, “The Dogma Is the Drama,” she employed sarcasm in a subverting and shocking manner as she lambasted the exchangist explanation:

“Q: What is meant by the Atonement?

A: God wanted to damn everybody, but His vindictive sadism was sated by the crucifixion of His own Son, who was quite innocent, and, therefore, a particularly attractive victim. He now only damns people who don’t follow Christ or who never heard of Him.”

As Downing comments, “Originally defined as ‘the removal of human sin as a hindrance to relationship with God,’ the atonement has been reduced, in many people’s minds, to an economy of exchange.” Some theologians have argued, relates Downing, that talk of the atonement needs to disappear due to its “sadism.” Sayers, though, “would argue that what we need to get rid of, instead, is language about ‘satisfaction and paying off’ that has turned Christianity into one among many exchangist religions. What we need is to hand over the atonement to the shock of the old: salvation as a payment-free gift.”

Chapter four, “The Subversive Mind of the Maker,” is a superb application of Sayers’s fascinating book of the same title. The main concepts here are the integrity of one’s work, the excellence in which one carries it out, and the ability to do so in a way that impacts those who find themselves confronted with that work, whether it be the craftsmanship of writing, painting, woodworking, or whatever talent God has given. In a 1946 letter to C. S. Lewis, Sayers opines,

I don’t believe He implants a love of good workmanship merely as a trap for one to walk into. Of course one can make an idol of good workmanship, as of anything else. I don’t know what will happen at the moment of death. But I don’t somehow fancy showing . . . a lot of stuff to the Carpenter’s Son and saying, “Well, I admit that the wood was green and the joints untrue and the glue bad, but it was all church furniture.”

Downing follows up that quote with an interweaving of her own thoughts with Sayers’s:

Furniture can be “bad” in construction even when intended for “good” purposes. She acknowledges that “pious souls,” welcoming anything with a Christian message, can “get comfort out of bad stained glass and sloppy hymns and music.” But such souls seem to value the message more than the people it is supposed to attract—much as Christians valued King James English more than the people Sayers wanted to reach through The Man Born to Be King. Poorly crafted evangelistic art, as Sayers explains to Lewis, has caused “thousands” to think, “If Christianity fosters that kind of thing it must have a lie in its soul.”

I will admit to being surprised (perhaps I should say “shocked”?) by chapter five, “The Politics of Religion, the Religion of Politics.” It was a pleasant surprise, however, as I am a professor of history and government.

I wondered, as I began this chapter, just how everything that preceded it would flow into this particular discussion. As it turns out, it flowed well. A quote from Sayers in her introduction to The Man Born to Be King, while obviously centered on her own nation, reminds us that people and governments have the same problems regardless of where we live or when.

God was executed by people painfully like us, in a society very similar to our own—in the over-ripeness of the most splendid and sophisticated Empire the world has ever seen. In a nation famous for its religious genius and under a government renowned for its efficiency, He was executed by a corrupt church, a timid politician, and a fickle proletariat led by professional agitators.

If that doesn’t sound contemporary, what does? Exchangism in current politics is rampant. Christians, “believing their candidate, if exchanged for the opposition’s candidate,” notes Downing, “will change the face of the world, either by returning the government to past policies or by propelling it toward promised programs. Ironically, of course, after four to eight years of a presidency, the opposite party often comes into power, many times overturning policies that the preceding party implemented with intelligence and hard work.”

Further, we rely on worn-out phrases, what Downing refers to as “disembodied terms” repeated mechanically. After a while, they lose their significance. As with theology, politics descends into glib phrases that lack any type of originality, thereby having one’s “audience” glaze over.

Indeed, once you hear one cliche from a political true believer, whether from the right or the left, you often can predict every other opinion he or she holds. That’s not creativity; it’s conformism; that’s not the image of the Trinity, it’s the trite. Either way, as Sayers put it in a book that immediately preceded The Mind of the Maker, “many people contrive never once to think for themselves from the cradle to the grave.”

And since one of Sayers’s key concepts is integrity, Downing captures her thought well when she adds, “Instead of using cliches that perpetuate polarized thought, it means generating language that acknowledges what is good about one’s opposition as well as what is problematic about one’s own party, for we are all both Cain and Abel; to deny this is a form of dishonesty. As Sayers explains to an undergraduate at Cambridge University, ‘One must not misrepresent matters, even in the interests of one’s own dogmatic convictions.'”

A shocking statement, for sure, as it seems to subvert American politics as it exists in our day.

Dr. Crystal Downing, in Subversive, has provided Christians a guide for how we can and should interact with our society, and her vehicle for doing so—the shocking Dorothy L. Sayers—was well-chosen for communicating this message.