It’s always important to define one’s terms before delving into an explanation of anything. I would like to begin with a definition of the following word:

Nuance: A subtle or slight degree of difference, as in meaning, feeling, or tone.

Expression or appreciation of subtle shades of meaning, feeling, or tone.

Nuance needs to be applied to history, especially in the current atmosphere where many are angry over injustices that have occurred in American history. There are three attitudes one can take toward America’s Founding Era.

- America was founded as an evil empire with the organic sin of slavery as its cornerstone.

- America was founded as the fountain of liberty and has always exhibited fidelity to that calling.

- America was founded on principles that laid a cornerstone of liberty that has done much good in the world, yet has had to struggle to become consistent with those principles.

The first two attitudes don’t really allow for nuance. The third attitude recognizes both the merits of America and the problems it has had to overcome to realize its ideals. The first two attitudes don’t allow for much rethinking. The third attitude accepts that rethinking is important but it doesn’t (as I resort to a cliche) throw the baby out with the bathwater.

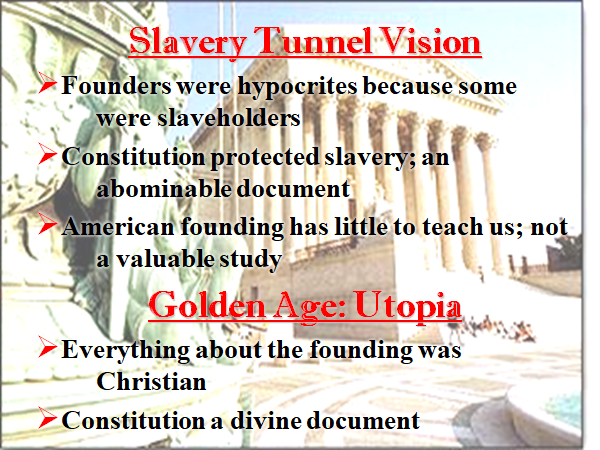

In my introductory American history course, I explain these first two interpretations of our early history in this way:

I refer to the first one as tunnel vision because for some people, they can see nothing else but slavery. That approach then denigrates any accomplishments in early America, including the Declaration of Independence, the War for Independence, and the Constitution.

Yet there are conservatives—and Christian conservatives, in particular—who many times succumb to the second interpretation, seeking to call everything Christian and overlooking the problems that remained. Neither do I consider the Constitution a divine document. It’s a good document, complete with a method for amending it. The men who wrote it knew they weren’t omniscient; it would need amending over time. There’s only one divine document in the world, and it contains an Old part and a New one.

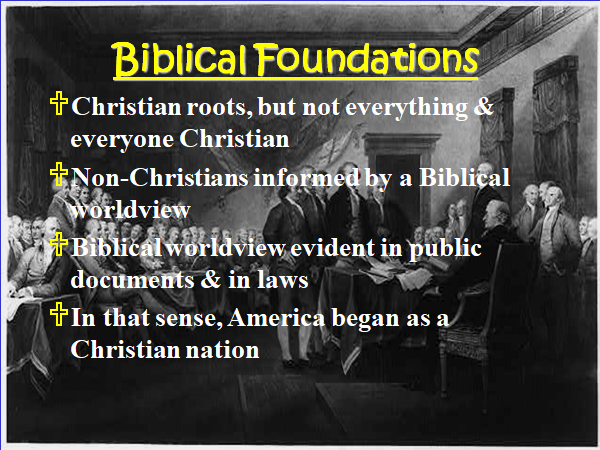

There is no nuance in these approaches to American history. That’s when I tell my students my particular approach, described on this slide:

In this approach, there is appreciation for what is good and noble in the Founding while acknowledging that not everyone was good and noble and not all things were Christian. It points to the basic Biblical worldview of the era, yet leaves open the opportunity to explain when the nation didn’t fulfill its goals.

In other words, there is historical nuance.

The “1619 Project” promoted by the New York Times attempts to depict the story of America’s Founding as a glorification of slavery. In its telling, this project says the American Revolution rested primarily on the protection of slavery.

I have studied the Revolutionary era in some depth over the past thirty-plus years. I don’t see that in the primary documents. Yes, some slaveholders were reticent to join any cause that they thought might inhibit slavery, but there is no strong thread in any documents I’ve seen of carrying out a revolution to ensure slavery’s existence. In fact, the promotion of liberty seemed to work in the opposite direction.

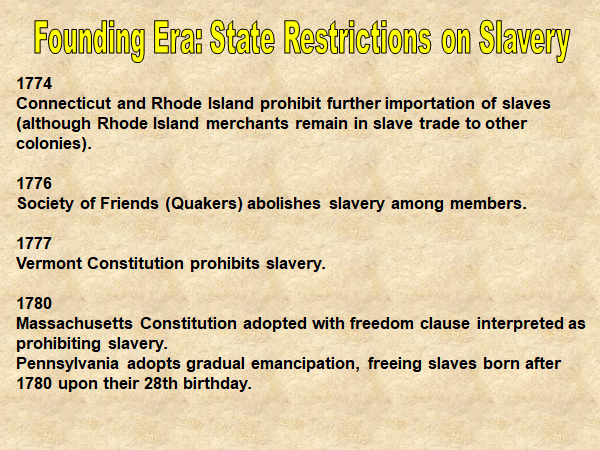

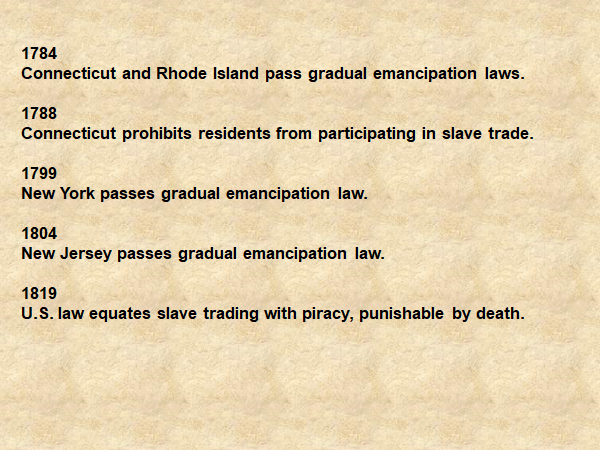

Even though Jefferson’s words in the Declaration of Independence where he states that all men are created equal probably meant, to him and many others at the time, that the colonists were on the same level and had the same status as British citizens in the Mother country, they were words that sparked a movement toward the abolition of slavery. Here, for instance, are examples of what various states did during this era to undermine the institution:

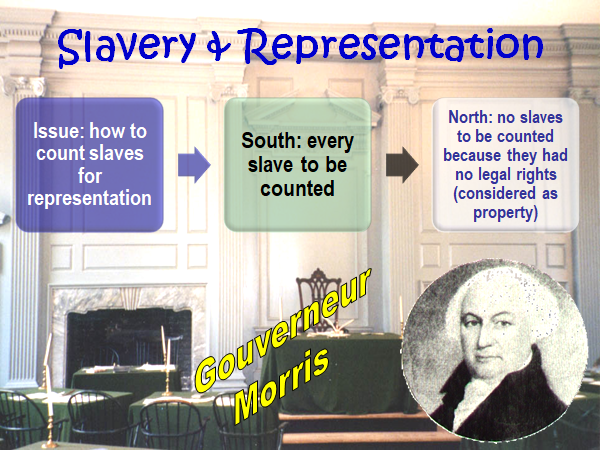

Then there’s the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The debates were vigorous, and slavery and its role in the population of the new nation was at the center of one of those debates.

Gouverneur Morris, the man at the bottom of the slide, was a delegate from New York. In the heat of the debate as outlined above, he challenged the southern delegates who wanted to count every slave toward how many representatives they would get in Congress. He kind of tweaked them, saying, “Are they men? Then make the citizens and let them vote. Are they property? Why then is no other property included?”

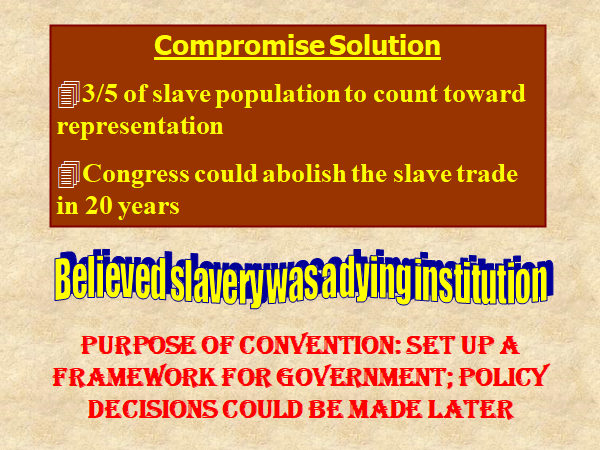

The debate was ended with a compromise, but a compromise that has been controversial ever since. Here is what was decided:

Counting 3/5 of the slave population for the purpose of representation gave the South more clout in the House of Representatives. Later, during the War of 1812, when Federalists in New England held a convention at Hartford, they recommended a constitutional amendment that would negate that 3/5 clause. That didn’t happen, but it remained controversial throughout the pre-Civil War years.

That slide, though, highlights some things that many are unaware of. First, the second half of that compromise was to allow Congress to pass a law that would stop the importation of slaves. That law did pass in 1807. Further, as noted above, most of the delegates were convinced that slavery was going to die out sooner or later. There was a growing consensus on that issue at the time. Therefore, a compromise seemed appropriate until that day arrived.

The final thought on the compromise is the realization that the purpose of the convention was not to settle all public policy issues, but to get a working government set up. The nation under the Articles of Confederation was ineffective, and if the convention were to break up over this, it was likely the nation as a whole would break up as well. In order to hold things together, a competent constitution was necessary. Once that was achieved, the Congress could then tackle issues, one of which certainly was slavery.

What the delegates couldn’t have known in 1787 was that seven years later, Eli Whitney would invent the cotton gin, making slavery more profitable. I don’t want to castigate the Founders for not banning slavery in 1787. The blame rests more with a later generation that avoided the issue and the development of a more strident pro-slavery position in the South.

As a sidelight, I recently learned that Whitney believed his cotton gin would actually reduce the need for slavery. He was disappointed when it went the other direction.

My goal here has been to showcase the nuances that ought to be taken into consideration when thinking about the American Founding. This doesn’t whitewash the evil of slavery, nor does it mitigate the damage done by the ensuing segregation that followed the Civil War. I merely want us to understand the Founders in their own era and what was accomplished.

Both sides in this current debate have a tendency to go to the extreme. Those who focus on the evil of slavery tend to think everything in America is tainted by it. Those who see the value of what was achieved for liberty and constitution-making tend to downplay the ongoing evil of slavery and how it infected the culture of the day. We need to have a clear view of what really occurred.

We need historical nuance.