We are in the midst of another impeachment drama, the third in my lifetime. The first, that of Richard Nixon, didn’t reach a full House vote or a Senate trial due to Nixon’s wise decision to resign. The second, that of Bill Clinton, went to the Senate but suffered from the tribalism that so affects us still today, with not even one Democrat voting to remove him from office.

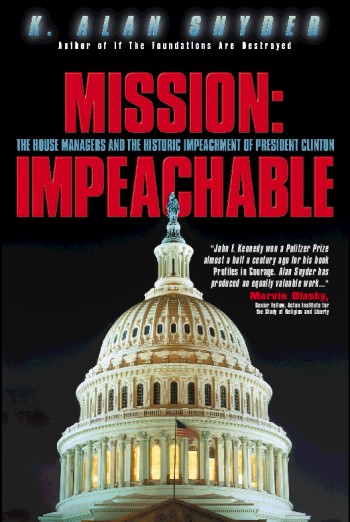

After that failed attempt to turn the presidency over to VP Al Gore (which would have been the result, thereby not really overturning the election), I embarked upon a quest to allow the House impeachment managers to tell their side of the story. Why did they proceed with this impeachment when none of the public opinion polls showed a majority of the people wanted Clinton removed? I interviewed personally all thirteen of them. The book you see here was the result.

I was impressed by their responses, all of which pointed to the need to stand by principle, to uphold the rule of law and the Constitution. They were all Republicans, of course, seeking to remove a Democrat from the presidency, yet I believed they meant what they said.

This current impeachment, though, now makes me wonder how many of those Republican managers really believed what they said. Were they genuine in their concern for principles and the rule of law or were they just as tribal as the Democrats who looked the other way when presented with Clinton’s impeachable offenses?

I dragged that book out again this morning and reacquainted myself with what I had written two decades ago. Yes, authors sometimes have to reread what they once wrote because time dims the memory. I discovered that anew this morning. I forgot that my first chapter included a section that covered the history of impeachment, focusing on just exactly what comprises impeachable offenses. That history, which was germane to the Clinton impeachment, is just as applicable to the Trump impeachment.

The most significant issue, of course, is what the Constitution considers impeachable offenses. It says specifically, “The President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” There is little debate over the nature of treason or bribery (although, in the current crisis, bribery could conceivably have been a basis for impeachment charges dealing with Ukraine), but the phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors” always has sparked considerable controversy.

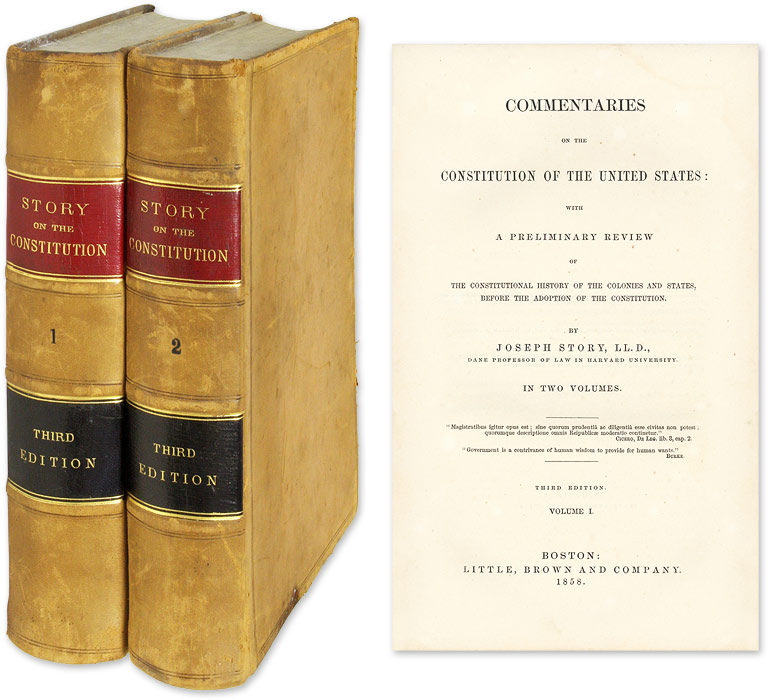

One of the most authoritative early American commentators on this subject was Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, who served on the Court from 1812 until his death in 1845, and who, in his 1840 Familiar Exposition of the Constitution, tackled the issue by embracing a combination of common sense and historical precedent. Story clearly did not believe that impeachment and removal from office required the breaking of a law. The history of impeachment is not something most people are familiar with, but there is plenty of evidence that we have strayed from the original concept of what may be considered impeachable offenses. Story was quite clear what history in his day had shown. His viewpoint deserves our close attention.

If we say that there are no other offenses, which are impeachable offenses, until Congress has enacted some law on the subject, then the Constitution, as to all crimes except treason and bribery, has remained a dead letter, up to the present hour.

Such a doctrine would be truly alarming and dangerous. Congress has unhesitatingly adopted the conclusion that no previous statute is necessary to authorize an impeachment for any official misconduct.

Further, Story noted, “In the few cases of impeachment, which have hitherto been tried, no one of the charges has rested upon any statutable misdemeanors.” Story’s view, then, was more than simply an opinion; early American impeachment practices confirmed it.

Yet today, we hear from some quarters that it takes an action against a specific law passed by Congress to rise to an impeachable offense. Story’s viewpoint that this is not the case is not a lonely viewpoint.

More on that in Part 2.