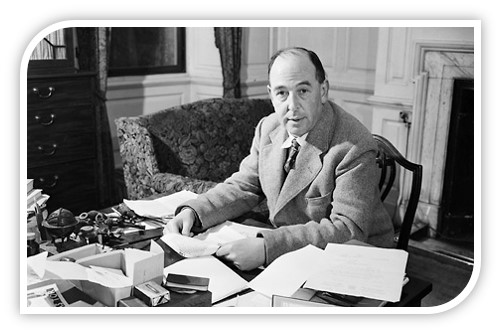

In my recent re-reading of C. S. Lewis’s The Four Loves, I came across a section that I had forgotten, which deals with one’s love of country—both the positive and negative aspects. This had a particular appeal to me as I prepare to teach American history once again to university students, many of whom are rather blank slates when it comes to knowledge of the past.

“We all know,” Lewis begins, “that this love [of country] becomes a demon when it becomes a god.” The same can be said of any kind of love that gets out of balance, and that, of course, is the point of the entire book. With love of country, he continues, “some begin to supect that it is never anything but a demon.” He doesn’t accept that: “But then they have to reject half the high poetry and half the heroic action our race [a word not intended in the same “racial” sense as today] has achieved. We cannot keep even Christ’s lament over Jerusalem. He too exhibits love for His country.”

Lewis distinguishes between what he calls “demoniac patriotism” and “healthy patriotism.” The former type makes it easier for rulers to act wickedly, while the latter makes it harder. “When they are wicked they may by propaganda encourage a demoniac condition of our sentiments in order to secure our acquiescence in their wickedness.” History is replete with examples of rulers getting their subjects to follow them into wickedness by appealing to patriotism. “That,” warns Lewis, “is one reason why we private persons should keep a wary eye on the health or disease of our own love for our country.”

Every country has its heroic moments in the popular imagination. When I teach American history, I want to highlight those moments, but I cannot ignore the less-than-heroic moments or I will be guilty of presenting a false picture. Yet a history that only focuses on those defects is not an accurate picture either.

The actual history of every country is full of shabby and even shameful doings. The heroic stories, if taken to be typical, give a false impression of it and are often themselves open to serious historical criticism.

Hence a patriotism based on our glorious past is fair game for the debunker. As knowledge increases it may snap and be converted into disillusioned cynicism, or may be maintained by a voluntary shutting of the eyes.

But who can condemn what clearly makes many people, at many important moments, behave so much better than they could have done without its help?

This bifurcation exists today in Americans’ reaction to our history. One group sees only the negative and decides that the country is evil; the other side sees only the positive and may have a tendency to ignore what has been wrong in its past. Lewis says we shouldn’t belong to either side.

“I think it is possible to be strengthened by the image of the past without being either deceived or puffed up,” he asserts. What’s the key?

“The image becomes dangerous in the precise degree to which it is mistaken, or substituted, for serious and systematic historical study.” In other words, both sides must be willing to look at the history afresh. The cynical debunkers need to acknowledge that there have indeed been heroic individuals and praiseworthy moments in our history. Likewise, those who have the perception that all is glorious in our history need to be willing to take a second look and achieve greater balance in their perspective. That balance is the aim of my teaching.

Lewis adds that one cannot truly love one’s country properly if one is quick to disown that country because of its faults. He provides an excellent analogy, I believe:

Love never spoke that way. It is like loving your children only “if they’re good,” your wife only while she keeps her looks, your husband only so long as he is famous and successful. “No man,” said one of the Greeks, “loves his city because it is great, but because it is his.”

A man who really loves his country will love her in her ruin and degeneration–“England, with all thy faults, I love thee still.”

That’s the attitude I hope to help instill into my students this year.