I’m now a member of a church that has a strong education program. On Wednesday evenings, for an hour and a half each week, I’ve had the joy of teaching C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters and Mere Christianity (along with my book, America Discovers C. S. Lewis). I’ve now been asked—and have readily agreed—to teach The Chronicles of Narnia. I won’t try to cram them all into one semester; instead, I’ll divide them into a two-semester format, covering the first three books in the fall and the final four in the winter/spring.

Preparation is already well underway. Although I’ve read them all previously, I knew it was essential that I go through them again, this time with precision, marking everything in the books that I might want to illuminate and that will, hopefully, produce Spirit-led discussion. My re-reading has been a joyful experience that I completed this past week.

I didn’t need to read The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe for the purpose of remembering what it is all about, of course. As the most well-known of the books, my goal was simply to see what I might have missed. When you go back to a book for that reason, and with a desire to communicate well with a class, you realize how much depth Lewis packs into what, ostensibly, is a children’s book. The sacrifice of Aslan on the Stone Table is profound as an illustration of what Jesus has done for all of us guilty sinners. The awfulness of the deed and the triumph of Aslan’s resurrection is not a story that speaks to children only; any thinking adult should be deeply moved by the love of God through it.

When I moved on to Prince Caspian, I must admit I wasn’t as excited to read it as I should have been. I think the whole battle theme and the fact that the Hollywood version added in elements alien to Lewis’s vision of the book had dampened my expectations for a re-read.

But upon reading it again, I came to the realization of how much I hadn’t remembered of the spiritual significance Lewis embedded within. No one can see Aslan except Lucy because they lacked faith. Lucy doesn’t follow Aslan’s instructions and trouble ensues. Afterwards, she stands strong even when no one else believes her. The romp through Narnia near the end of the book when Aslan sets people free from the draconian measures to which they have been subjected highlights Lewis’s superb sense of humor. I found it more refreshing than I expected.

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader was pure delight. Eustace being “dragoned” and the lesson of how only God can “undragon” us was one I already knew, but reading it again gave it new life. The series of adventures on the voyage I had largely forgotten. The movie version of the book has come under much criticism for departing from Lewis’s intent. Since I hadn’t read the book for a while, I hadn’t picked up on the specifics of the critics. As I review the film this time, I’ll analyze the distinctions more carefully.

Puddleglum is one of the best characters Lewis ever created. My re-read of The Silver Chair brought that out more clearly than ever. Again, I was amazed at how much I had forgotten with respect to the details of the story. This tale is a gem that calls for a cinematic portrayal worthy of Lewis. There was one supposedly coming that seems to be in limbo. Now that Douglas Gresham has an agreement with Netflix to develop Narnia, we can hope this book will get the treatment it deserves.

The Horse and His Boy was probably the book I recalled least in the series, and I wondered how it would come across to me this time. I was more than pleasantly surprised.

I may sound like I’m repeating myself (because I am), but once more I was impressed with the depth of the message. Fans of Narnia are correct when they say there are many layers to the series: one at children’s level, of course, but another at pure reading enjoyment for all ages, and another that brings spiritual understanding. By setting this story in a land where a false god and a totalitarian government rule, the contrast with Narnia, where the true God reigns and the government is under His authority, is stark. And yet, it is also the personal story of two young people who need to find the truth about their lives. Lewis told this one magnificently.

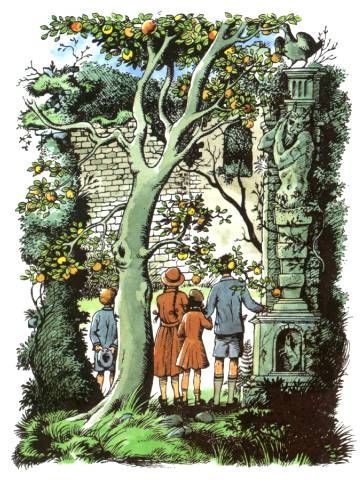

Some readers think The Magician’s Nephew should be read first in the series simply because it shows the creation of Narnia—it’s the foundation for all that follows. Yet I still like the original reading order. What’s great about this book is that after reading the previous five, the details included here give meaning to so much one has read previously. No, this is where it belongs as we get the backstory for where the White Witch came from, why there is a lamppost in the forest, and how the wardrobe became a conduit from our world into Narnia. I found it delightful to see all the connections and how it all came together in Lewis’s mind over time. The Magician’s Nephew took the longest to write as he, at first, struggled to tell the tale, but I believe it ranks as one of the best in the series.

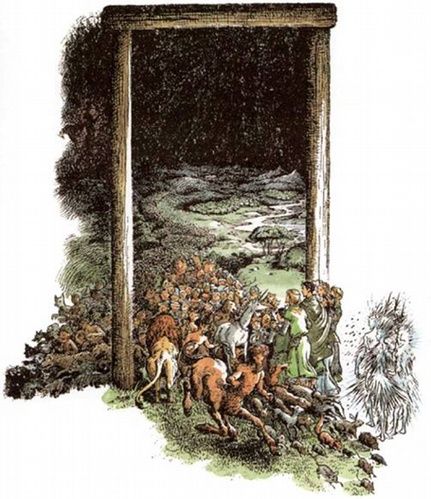

How poignant that Lewis followed up the creation of Narnia with how it came to an end. The Last Battle, and particularly the final chapter and the final few paragraphs of the book, never fail to bring tears of joy and the hope of heaven to my heart. Only a writer who has that hope of heaven within him can convey it as strikingly as Lewis does here. The sadness of the Last Judgment and the subsequent joys of eternity that he describes are sublime. This is the Narnia book I give to my students who take my Lewis class at the university. I want them exposed to what it means to enter into eternal life.

I’m using a number of other books that will help me expound on the stories, and I will show portions of the Hollywood films, as well as the BBC productions, but more than anything else, I want those who take my classes on Narnia to allow the stories themselves to transport them into Lewis’s world. All of the spiritual lessons should follow in the wake of being first transported.