I’m down to the last couple of weeks now for my Southeastern University course on C. S. Lewis. I’ve had the students read many of his most revered books and essays. They’ve worked through—with love, I trust—Surprised by Joy, Mere Christianity, The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, That Hideous Strength, and The Last Battle.

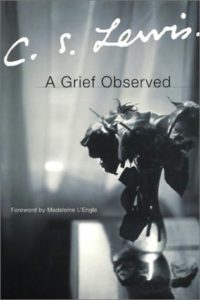

This past week, they read A Grief Observed, Lewis’s most personal little book, a heart cry for the presence of God after suffering the loss of Joy, his wife. I wondered how they would receive it, seeing as how it offers a different side of Lewis—one that’s questioning God’s character and His love before ultimately coming to a resolution that shows how his faith holds in the midst of trial.

This past week, they read A Grief Observed, Lewis’s most personal little book, a heart cry for the presence of God after suffering the loss of Joy, his wife. I wondered how they would receive it, seeing as how it offers a different side of Lewis—one that’s questioning God’s character and His love before ultimately coming to a resolution that shows how his faith holds in the midst of trial.

They appreciated it deeply, from what I could discern in our discussion of the book.

One might be shaken somewhat by Lewis’s doubts at this time in his life. After all, near the beginning, he complains that when you go to God in desperate need, you find “a door slammed in your face, and a sound of bolting and double bolting on the inside. After that, silence.”

He then questions the reality of his own faith. The man who has spent his life strengthening the faith of others seems to fall apart in his distress:

You never know how much you really believe anything until its truth or falsehood becomes a matter of life and death to you. It is easy to say you believe a rope to be strong and sound as long as you are merely using it to cord a box. But suppose you had to hang by that rope over a precipice. Wouldn’t you then first discover how much you really trusted it?

As a Christian, Lewis admits that he already knew that death comes to all and that sufferings were part of life. “I would have said that I had taken them into account. I had been warned—I had warned myself—not to reckon on worldly happiness. We were even promised sufferings. They were part of the program.”

Yet when hit by the loss of his wife, he was sent reeling and wondering about his faith:

It is different when the thing happens to oneself, not to others, and in reality, not in imagination. Yes; but should it, for a sane man, make quite such a difference as this? No. . . .

The case is too plain. If my house has collapsed at one blow, that is because it was a house of cards. The faith which “took these things into account” was not faith but imagination.

As Lewis stumbles toward understanding, he sees God as a surgeon with good intentions. Yet those good intentions don’t spare the patient the pain he must endure. “The kinder and more conscientious he is, the more inexorably he will go on cutting. If he yielded to your entreaties, if he stopped before the operation was complete, all the pain up to that point would have been useless.”

Lewis then revisits that bolted door, the one he blamed God for bolting against him.

I have gradually been coming to feel that the door is no longer shut and bolted. Was it my own frantic need that slammed it in my face? The time when there is nothing at all in your soul except a cry for help may be just the time when God can’t give it: you are like the drowning man who can’t be helped because he clutches and grabs. Perhaps your own reiterated cries deafen you to the voice you hoped to hear.

I believe the turning point for Lewis came when he realized that he had been focusing on himself—allowing his hurts, his internal angst, his needs—to drive his thinking. The order was him first, Joy second, and God last. “The order and the proportions exactly what they ought not to have been.”

It’s only when we get out of ourselves that we can see clearly once more. As his thoughts turn back to God first, he questions his motives: is he coming back to Him only as a way to reconnect with his wife eventually? Clarity returns with these words:

I know perfectly well that He can’t be used as a road. If you’re approaching Him not as the goal but as a road, not as the end but as a means, you’re not really approaching Him at all.

That’s what was really wrong with all those popular pictures of happy reunions “on the further shore”; not the simple-minded and very earthly images, but the fact that they make an End of what we can get only as a by-product of the true End.

So Lewis returned, and his letters in those final three years of his life attest to his vibrant faith. He walked through the valley of the shadow of death and emerged not with a house of cards, but with that proverbial house built on the Rock.