Politics. Is there anyone else besides me who wishes he/she could turn it off for a while? I’m a professor of American history, though, so it’s important for me to keep up with political developments and provide analysis—for my students, of course, but I also feel a responsibility to help others understand the principles we need to follow.

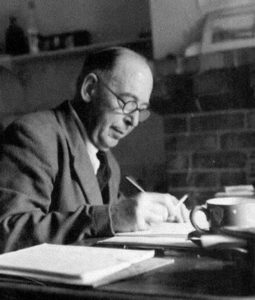

There is a temptation, though, to be so immersed in politics that one sees it as all-consuming. C. S. Lewis recognized that temptation. In his day, WWII was one of those potentially all-consuming events. Some people, at that time, were saying that all other activities, including Lewis’s own profession as a professor, should be set aside so that all thought and energy would be concentrated on the war.

Lewis said no to that. One of his most enlightening essays, “Learning in War-Time,” addressed the complaint that some had about allowing normal day-to-day activities to continue uninterrupted.

Lewis said no to that. One of his most enlightening essays, “Learning in War-Time,” addressed the complaint that some had about allowing normal day-to-day activities to continue uninterrupted.

Lewis wanted to be sure he was not misunderstood: the war was a righteous one and every citizen had a duty to support it. “Every duty is a religious duty,” he believed, “and our obligation to perform every duty is therefore absolute.”

Rescuing a drowning man is a duty, he continued, and if we happened to live on a coast, perhaps we should be well prepared as lifesavers. But even such a laudatory effort as lifesaving needs to be seen as only part of one’s overall duties.

If anyone devoted himself to lifesaving in the sense of giving it his total attention—so that he thought and spoke of nothing else and demanded the cessation of all other human activities until everyone had learned to swim—he would be a monomaniac.

The rescue of drowning men is, then, a duty worth dying for, but not worth living for.

Lewis then opined that all political duties were like that. Politics is not the sum total of life. Seeking to put the right people in political office is a worthy endeavor, but it should never consume one’s life.

He who surrenders himself without reservation to the temporal claims of a nation, or a party, or a class is rendering to Caesar that which, of all things, most emphatically belongs to God: himself.

For Lewis personally, God had charted a course for his life that pointed to intellectual activity, something that was not to cease simply because a war was going on. One of his most famous quotes comes from this essay: “Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason, because bad philosophy needs to be answered.”

He then offers me, as a historian, this encouraging word:

Most of all, perhaps, we need intimate knowledge of the past. Not that the past has any magic about it, but because we cannot study the future, and yet need something to set against the present, to remind us that the basic assumptions have been quite different in different periods and that much which seems certain to the uneducated is merely temporary fashion.

A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village; the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.

There continues to be a “great cataract of nonsense” in our day. The America of 2018 suffers from a type of myopia, forgetting what has gone before, never learning from the past. History offers us tremendous lessons if we are willing to learn from them.

The reason I am so focused, at times, on the current political situation, is that I am disturbed by our ignorance of the past and our apparent unwillingness to correct what we have done wrong previously. We think we are charting a new course that will lead us to some type of utopia when, in fact, we are simply following some of the same old ruts that have caused misery before.

Lewis concludes his essay with what WWII should teach his generation. His conclusion applies to our generation as well if we think political programs or putting the right person in office will be our savior:

If we had foolish un-Christian hopes about human culture, they are now shattered. If we thought we were building up a heaven on earth, if we looked for something that would turn the present world from a place of pilgrimage into a permanent city satisfying the soul of man, we are disillusioned, and not a moment too soon.

We must never forget that we are pilgrims on this earth, and that the pilgrimage goes on regardless of what happens in politics and government.