When is compromise right? When is it wrong? When I look at historical compromises, I try to apply this rule:

A compromised principle leads to unrighteousness, but a principled compromise is a step closer to the principle’s ideal.

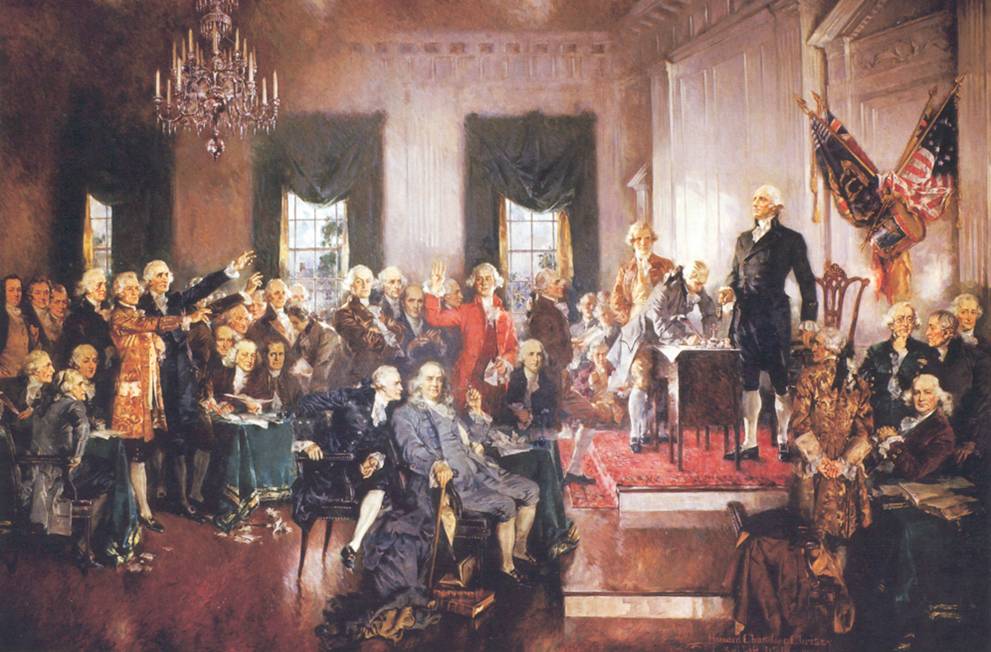

Let’s take the Constitutional Convention as an example.

The delegates who comprised the convention that led to our current Constitution had to grapple with a number of controversial issues. The two most prominent were how to carry out proper representation and how to incorporate the existence of slavery within the document.

On the issue of representation, states with greater population argued that they should have more say in the making of the laws. After all, they had more people, so it only seemed fair to them.

The smaller states, however, fearing that they would always be outvoted on matters of concern to them that might not concern larger states, called for equal representation in the newly proposed government.

Who had the better argument?

In this case, both were making good points. Both arguments had validity.

Consequently, a compromise was forged that led to setting up two houses in the national legislature (as opposed to one in the Congress established by the Articles of Confederation). The House of Representatives would be allotted a proportional number of members based on each state’s population while the Senate would have two members from each state, thereby providing a chamber where the smaller states had an equal vote.

In my view, this was an acceptable compromise that answered the concerns of both parties. No one sacrificed a principle.

The other thorny issue was whether to count the slaves as part of the population of a state. If all slaves were counted, that would definitely give slave states a higher number of representatives in the House. The Southern states, therefore, favored this position.

Northern states, many of whom had already abolished slavery while others were in the process of doing so, thought that would be unfair. After all, as Gouverneur Morris of New York postulated in the debate,

Northern states, many of whom had already abolished slavery while others were in the process of doing so, thought that would be unfair. After all, as Gouverneur Morris of New York postulated in the debate,

Are they men? Then make them citizens and let them vote. Are they property? Why then is no other property included?

Fair question. What was to be done?

The convention came up with this compromise: count 3/5 of the slave population toward a state’s representation (not all the slaves, as the South desired); allow the Congress, twenty years hence, to pass a law that would prohibit the importation of more slaves into the country.

That latter provision was based on a sincere wish that most of those delegates had: the eventual elimination of slavery in America. They hoped that such a law would dry up the slave population over time.

Incidentally, twenty years later, Congress did pass that law.

Was this an acceptable compromise? People are divided on that. Personally, I would have welcomed a stronger stance against slavery, but I also understand the tenor of the times and the limitations on what that convention needed to accomplish.

The Constitutional Convention couldn’t hope to achieve unanimity on the issue of the continuance of slavery. What it could hope to achieve was to set up a working government that could then deal more fully with the issue.

That was accomplished. The sad fact that Congress, over the next few decades, didn’t come to grips with slavery as it should have is not something that should be laid at the feet of those at the Convention.

In fact, based on what they knew at the time, there was good reason to believe slavery was already on its way out. It was not as profitable as expected.

What changed? How about the invention of the cotton gin seven years later, which made slavery far more profitable?

Let’s not play a blame game that holds people responsible for something that happened seven years in the future. That would be like holding people in 2018 responsible for something that will occur in 2025 that alters the whole perspective of an issue.

We’re not really all that good at knowing what the future holds, given the millions of individual choices of citizens that will be made along the way.

It’s possible, therefore, to consider even that slavery compromise as a principled one, despite the disrepute it has earned over time.

The main lesson here, I believe, is to work toward compromises that move the ball toward what one wants to see eventually. Any step in the right direction should be welcomed.