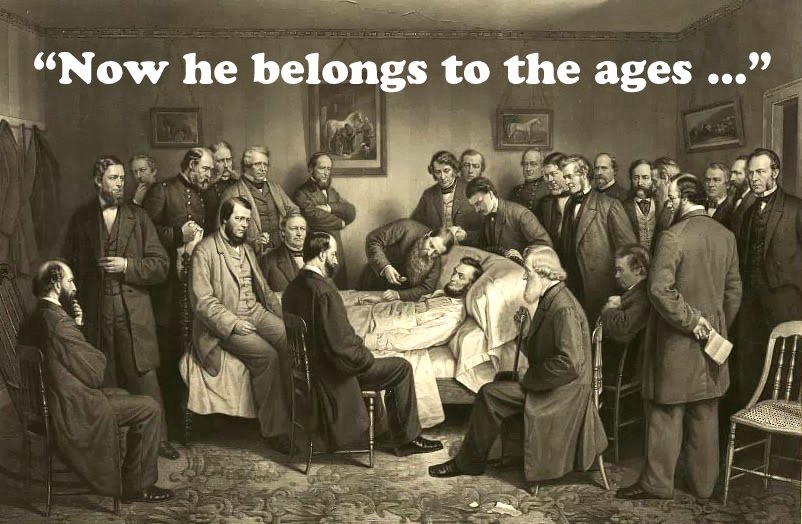

On the morning of April 15, 1865, Abraham Lincoln died in a house across the street from Ford’s Theater. The pandemonium of the night before still resonated through Washington, DC, and the news would soon spread throughout the country, both North and South.

John Hay, Lincoln’s personal secretary, recalls hearing these words from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton:

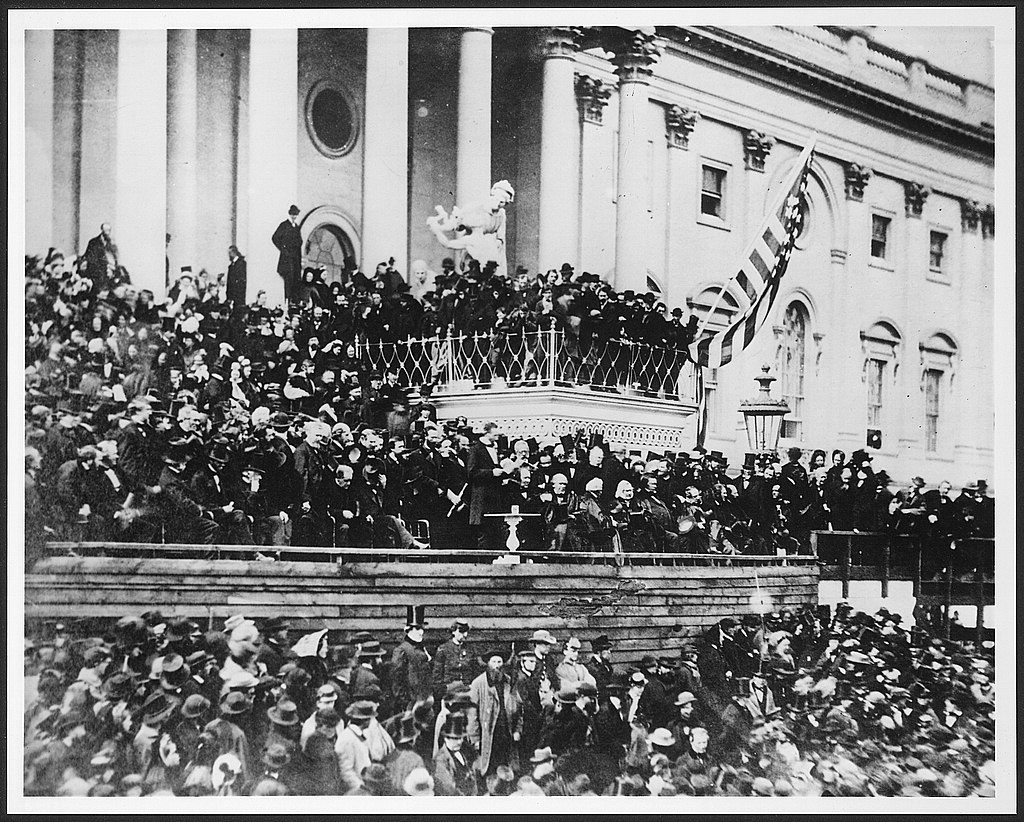

The nation mourned, and it wasn’t just the North that did so. Many in the South knew this was a tragedy for them as well. Lincoln had mapped out a policy of forgiveness and reconciliation with the transgressing states. His main hope was a peaceful reunification without rancor. He stated his position eloquently in his Second Inaugural Address.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

The portrait painted by some today, that Lincoln was a tyrant who trampled on the Constitution and abused his office, is inaccurate. I won’t go into all the details in this post, but suffice to say that I was one who leaned in that direction early in my career. I don’t believe that now. Why the change? Let’s just say that more historical research proved to me the opposite.

Lincoln was a man who was drawn steadily back to the Christian faith after years of agnosticism. The trial of the Civil War deeply affected him and forced him to turn his eyes Heavenward.

His speeches and letters during that awful war reveal a man who is in the throes of a great spiritual introspection—an introspection that exhibited itself in both his Gettysburg Address and in that Second Inaugural.

The heart of the Second Inaugural—and the heart of Lincoln himself—can be found in this short excerpt:

Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other.

It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged.

The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.

“Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.”

If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him?

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

The loss of Lincoln at that critical point in American history was huge. Reconciliation did not prevail at that time; it took far longer to heal the brokenness and the racial attitudes than it should have.

We still bear those scars today.