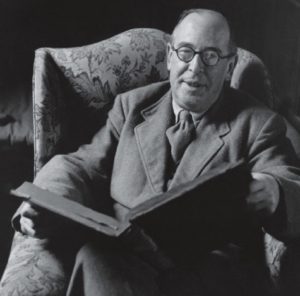

What’s perhaps the biggest deception in our day that keeps people from getting their lives right with God? I want to draw from three C. S. Lewis writings to offer one possibility—a possibility that I think is far closer to a probability.

In Lewis’s classic Mere Christianity, the path to establishing a relationship with God is clearly laid out:

In Lewis’s classic Mere Christianity, the path to establishing a relationship with God is clearly laid out:

Christianity tells people to repent and promises them forgiveness. It therefore has nothing (as far as I know) to say to people who do not know that they need any forgiveness.

It is after you have realised that there is a real Moral Law, and a Power behind the law, and that you have broken that law and put yourself wrong with that Power–it is after all this, and not a moment sooner, that Christianity begins to talk.

When you are sick, you will listen to the doctor.

But not until then. And our age is awash with people who have no sense of estrangement from God because they have been indoctrinated away from the guilt they used to feel.

This makes us different from earlier ages, Lewis posits. He explains this in his “Christian Apologetics” essay in this way:

A sense of sin is almost totally lacking. Our situation is thus very different from that of the Apostles. The Pagans (and still more the metuentes [i.e., the God-fearing Gentiles]) to whom they preached were haunted by a sense of guilt and to them the Gospel was, therefore, “good news.”

What has changed?

We address people who have been trained to believe that whatever goes wrong in the world is someone else’s fault–the Capitalists’, the Government’s, the Nazis’, the Generals’ etc.

They approach God Himself as His judges. They want to know, not whether they can be acquitted for sin, but whether He can be acquitted for creating such a world.

In other words, we have turned the tables on reality. We, in our arrogance and pride, demand that God answer to us. We are not to blame—God is.

Lewis makes the same point in another essay, “God in the Dock,” in which he diagnoses the problem he has faced speaking to certain groups:

The greatest barrier I have met is the almost total absence from the minds of my audience of any sense of sin. This has struck me more forcibly when I spoke to the R.A.F. than when I spoke to students.

Given the state of events on university campuses today, I suspect if Lewis could return to speak in that venue, he might have to revise that statement. He continues:

Whether (as I believe) the Proletariat is more self-righteous than other classes, or whether educated people are cleverer at concealing their pride, this creates for us a new situation. The early Christian preachers could assume in their hearers, whether Jews, Metuentes or Pagans, a sense of guilt. . . .

Thus the Christian message was in those days unmistakably the Evangelium, the Good News. It promised healing to those who knew they were sick.

We have to convince our hearers of the unwelcome diagnosis before we can expect them to welcome the news of the remedy.

We are now in a society where a large portion of the citizenry have consciously pawned off their own personal sin and guilt to anyone or anything else in an effort to ignore what their consciences, prior to their re-education, always told them.

We are not guilty; we are victims. Our parents are to blame; the hypocrisy of the church is to blame; the rich are the oppressors; the government causes all the problems—the list of blameworthy entities is virtually unending.

Yet each individual must come to the place of recognizing one’s own sin and the justification for the guilt that accompanies it. We must stop playing the victim card. We must face the reality of our rebellion against a loving God who is always willing to forgive.

Yet each individual must come to the place of recognizing one’s own sin and the justification for the guilt that accompanies it. We must stop playing the victim card. We must face the reality of our rebellion against a loving God who is always willing to forgive.

But that forgiveness is conditional: sincere repentance, faith in the Son of God who gave Himself for us, and obedience to His commands.