Historians have a unique experience when they do research into individuals. Even though I have never met most of the people I’ve researched, I come away with the sensation that I know them anyway.

My master’s thesis was on Yale president (and clergyman) Timothy Dwight and American geographer (and clergyman) Jedidiah Morse, the latter being the father of Samuel F. B. Morse of telegraph fame.

My doctoral dissertation was on Noah Webster, the premier educator of early America and the compiler of America’s first dictionary, which bears his name.

Reading everything I can get my hands on that relates to Whittaker Chambers, Ronald Reagan, and C. S. Lewis has been an ongoing joy.

I can testify the same about Billy Graham, since I’ve not only researched at Wheaton’s Billy Graham Center, but also have looked into his correspondence and relationships with all the post-WWII presidents.

Graham built a reputation as a friend and counselor for many of these presidents, although his first attempt was a little rocky. He received an invitation to speak with Harry Truman in the Oval Office. He prayed with Truman at the end of the meeting. When he and his associates emerged from the White House, reporters wanted him to reenact that prayer. He obliged.

Although Graham was undoubtedly sincere in his action, Truman was incensed that something private would be made into a public spectacle. Graham, young and inexperienced in dealing with the media, learned a valuable lesson that day.

The young evangelist made a connection with a much older man, Dwight Eisenhower, when Truman left office. In one way, it’s rather amazing that Eisenhower, the general who successfully conducted the D-Day invasion, would find a spiritual guide in such a young man. Yet he asked Graham for suggestions of Biblical passages to use in his first inaugural.

As Eisenhower lay in bed at Walter Reed hospital, knowing he was going to die soon, he asked Graham to come see him and tell him one more time how to make sure he was ready to meet the Lord. If not for Graham, Eisenhower might never have made his peace with God.

Graham didn’t know Kennedy that well, but at the latter’s urging, they met after the election and before the inauguration, because Kennedy, as the nation’s first Catholic president, sought to show that the leading evangelical Protestant voice was not opposed to his presidency.

It’s noteworthy that at a time when many Protestants were concerned about having a Catholic for president that Graham accepted the invitation and was willing to stand publicly with Kennedy. He wanted to help heal that division between Christian denominations.

What may not be as well known is that Graham, in November of 1963, had a strong urge to call Kennedy and tell him the Lord had impressed upon him that the upcoming trip to Dallas might be dangerous. He never reached Kennedy; others in the administration put him off. We all know what happened next.

Lyndon Johnson was a profane man with whom one might think Graham would want nothing to do, but that was not the case. The two developed a close friendship, and Graham even got involved to some extent in some of LBJ’s initiatives on racial reconciliation and other policy issues.

Interestingly, LBJ tried to convince Graham to run for president. He demurred, knowing that God had given him a different calling. In my opinion, after reading through quite a bit of material on their relationship, I see LBJ wanting Graham to be close to him because he suffered a deep insecurity about his own spiritual state—an insecurity that he definitely should have had, given his low standard of morality. Perhaps he perceived Graham to be his “security blanket,” spiritually speaking.

In the public mind, Graham is most often associated with Nixon. It’s true that they were very close. It was during Nixon’s presidency that Sunday morning services were arranged at the White House, and Graham spoke at many of them. Although he never officially endorsed any president, there was little doubt that he supported Nixon’s reelection in 1972.

Then came Watergate. When the tapes revealed language from Nixon that Graham had never heard him use in his presence, he was deeply disturbed. On Nixon’s part, because he didn’t want the controversy swirling around him to impugn Graham’s ministry, he conscientiously avoided meeting with Graham once the Watergate investigation went into high gear.

What’s most touching, to me, is that nothing Nixon did pushed Graham away from him. Even in the disgrace of resignation from the presidency, Graham remained his friend and spiritual advisor. He was not seeking power with the high and mighty; he simply wanted to share God’s love with them. He was the friend of presidents even when they were no longer in office and had nothing to offer.

His close brush with a possible taint on his ministry led Graham to rethink his associations with presidents. It’s not that he sought to distance himself spiritually, but he never again wanted to be so public in his relationships with them that the ministry would be discredited.

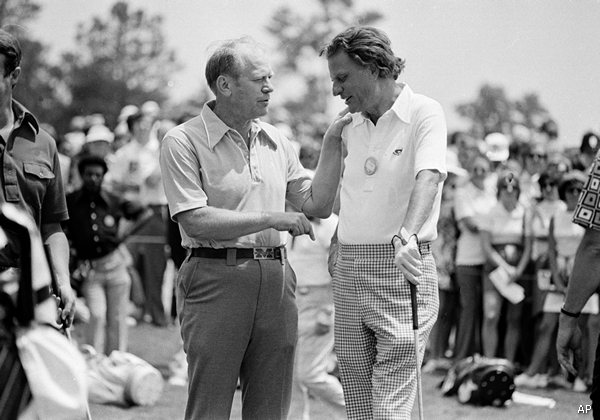

So when Ford took over from Nixon, while he did speak with the new president on occasions, he deliberately took a step back from a too-public connection.

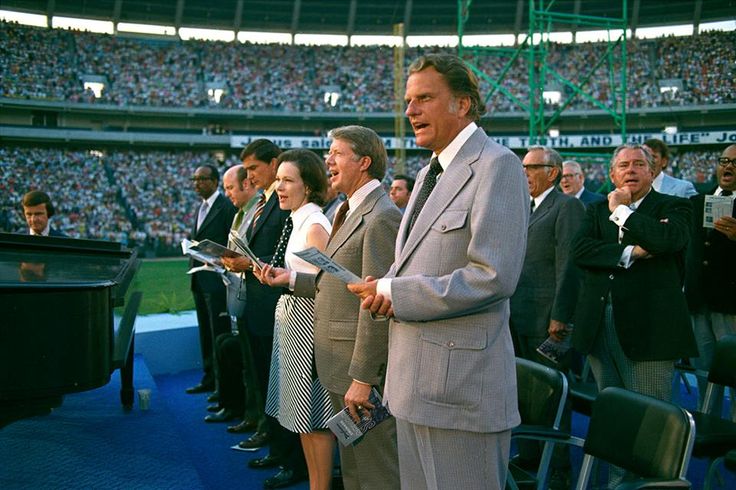

The same is true of his relationship with Carter. Prior to his presidency, Carter had even shared the stage with Graham in Georgia at one of his crusades.

Yet, the relationship was never very close. Carter considered himself his own spiritual advisor, some would say. He didn’t reach out much to Graham during his tenure in office.

Ronald Reagan and Graham had been friends for a couple of decades before Reagan won the presidency, so the link between them already was firmly established. According to some sources, Reagan was the president Graham was closest to, but, in the wake of Watergate, Graham was intent on keeping their communication as private as possible.

That’s kind of a frustration for a historian like me. Whereas I found a lot of correspondence between Graham and LBJ and Nixon, the Reagan Library yielded far less.

Reagan’s esteem for Graham was shown in his decision to award him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

When I interviewed Reagan’s pastor, Donn Moomaw, back in 2014, he lent me this photo that I downloaded into my own files. I’ll always appreciate his willingness to do that.

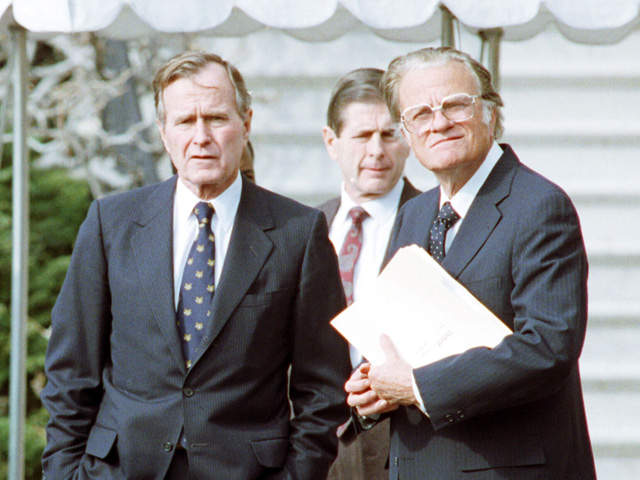

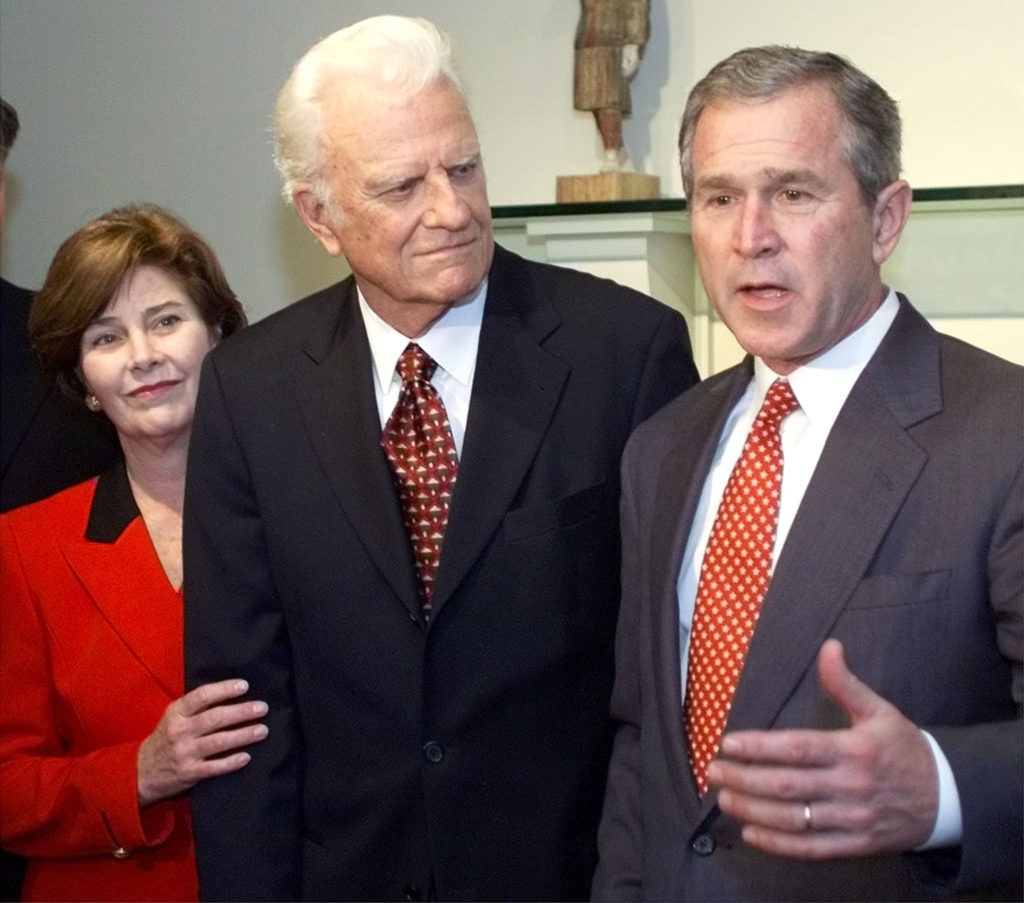

George Bush the elder also had a long-standing friendship with Graham, to the point that he invited him to the Bush compound in Maine annually. He wanted his family to hear from Graham on spiritual matters. His initial idea was to ask Graham to speak to them—like a sermon—but Graham instead just opened it up each year to questions, which was a much more personable approach.

It was on one of those occasions that a walk along the beach with George Bush the younger led to his commitment to follow the Lord.

Have I omitted anyone? Oh, yes, there was another one.

This is further evidence that Graham was willing to be a friend to anyone occupying the highest office in the land.

I hope this travelogue through the history of Billy Graham’s relationships and connections with presidents has been worthwhile for those of you who made it through this entire blog.

I thank God for using this man in our nation’s history. May many more rise up and be His spokesmen for truth.