In our era, when the rule of law seems to be weakening, it’s instructive to look back at how our cornerstone document, the Constitution, came into being. The 1780s, under the Articles of Confederation, saw a loose-knit assemblage of states that were in danger of splitting apart permanently. Those with concern for the rule of law and who had a vision for a better system urged a meeting of all the states to address the governmental crisis.

Twelve of the thirteen states responded to that call—tiny Rhode Island excepted due to fear of being overwhelmed by any change in the government—and sent delegates to Philadelphia. They met in this building in the summer of 1787, newly called Independence Hall, the place where they also debated and passed the Declaration of Independence eleven years earlier.

Twelve of the thirteen states responded to that call—tiny Rhode Island excepted due to fear of being overwhelmed by any change in the government—and sent delegates to Philadelphia. They met in this building in the summer of 1787, newly called Independence Hall, the place where they also debated and passed the Declaration of Independence eleven years earlier.

Of the thirty-nine individuals who eventually signed off on the new Constitution, over half had some training in the law. Lawyer jokes aside, that’s rather important, and was doubly so at that time, since all of them perceived of law as emanating from God ultimately, and not man.

They held to the conviction that man’s laws had to be in concert with God’s laws; otherwise, they would be invalid.

Half of the delegates had either attended or graduated from college. While that might seem to be a low percentage from the perspective of the twenty-first century, that was a high percentage in that era.

Further, thirty-three had served in the Continental Congress during the Revolution, a mark of stability and experience in governmental affairs. This was not to be an assembly of radicals who wanted to change everything.

Then, by choosing George Washington to preside over the convention, they provided its deliberations a respectability that all Americans would have to take seriously.

One delegate showed up with a plan: James Madison, probably the best researcher in the nation on the issue of good and effective government, offered his Virginia Plan, which became the basis for the debate as the convention went forward.

One delegate showed up with a plan: James Madison, probably the best researcher in the nation on the issue of good and effective government, offered his Virginia Plan, which became the basis for the debate as the convention went forward.

Madison’s influence was strong throughout that summer. He spoke frequently (second-highest number of speeches) and kept a record of what everyone said. Later, after all the delegates had died, his notes were published, and that book is now considered one of the most valuable of all American historical documents.

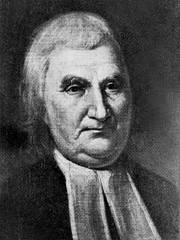

Another man, too infirm to be a delegate at this time, nevertheless made his mark on the Constitution because he was Madison’s mentor. Rev. John Witherspoon, president of the College of New Jersey, guided all of Madison’s intellectual pursuits. They had even worked together in the Continental Congress.

Witherspoon is credited, during his time at the college (later to be renamed Princeton) with graduating, along with the expected ministers, many men who later became governmental leaders. Four others at the convention, besides Madison, had studied under Witherspoon. Overall, the graduates during his tenure account for a future president (Madison), a vice president (Aaron Burr, but don’t hold that against Witherspoon), nine cabinet officers, twenty-one senators, thirty-nine congressmen, three US Supreme Court justices, and twelve state governors.

Witherspoon is credited, during his time at the college (later to be renamed Princeton) with graduating, along with the expected ministers, many men who later became governmental leaders. Four others at the convention, besides Madison, had studied under Witherspoon. Overall, the graduates during his tenure account for a future president (Madison), a vice president (Aaron Burr, but don’t hold that against Witherspoon), nine cabinet officers, twenty-one senators, thirty-nine congressmen, three US Supreme Court justices, and twelve state governors.

There is ample reason to accept the title many have bestowed on Witherspoon as “The Man Who Shaped the Men Who Shaped America.”

Some of what occurred at the Constitutional Convention will be the subject of a future post. Sufficient for today is the result: a system of government that gave precedence to the rule of law for a fledgling nation and that has helped that nation survive many tumultuous episodes. Regardless of our concerns with how our government may be functioning now, we can still feel some measure of confidence in its stability due to the wisdom of those who constructed it.