Monument: “Something venerated for its enduring historic significance or association with a notable past person or thing.” Memorial: “Something, such as a monument or holiday, intended to celebrate or honor the memory of a person or an event.”

As a historian, I’m into monuments and memorials. I want historic events and significant people in history to be remembered. Sometimes, I want them remembered because they deserve honor; other times, they should be remembered as valuable lessons of what can go wrong.

Auschwitz is a memorial to those who lost their lives in Hitler’s Holocaust. No one of sound mind would consider it a veneration or celebration of a historic event. Yet it serves a purpose: a reminder that we should never allow this to happen again.

So even awful things that have occurred in history should be recalled for our benefit. We have to be sure, though, that we have the right reason for the monument or memorial.

Which brings me to the current desire of some to tear down monuments to those who served the Confederacy during America’s Civil War. A lot of heat has been generated on this issue, but a lot less rational thought.

A little personal history here. In my early days studying history, I had sympathy for the Southern position because I believe in our federal system of government that leaves most decisions to the states. My concern for overreaching federal power led me to think that Lincoln and the North should have allowed the Southern states to secede without intervening.

Then something happened: I studied more. I came to realize that the secession was illegitimate constitutionally; I eventually saw that the states’ rights argument, in this particular case, always revolved around defending slavery as a positive good; I saw more clearly the attitude of the South and its aggressiveness in seeking to spread slavery into more areas; and I read a lot of what Lincoln had to say and gained tremendous respect for his constitutional basis and decency as a man.

In short, I changed my mind about the Civil War. Those who took leadership in the South, both in its government and in the military, were in rebellion against the legitimately elected American government.

Now, I may have just lost some readers who continue to believe otherwise, but stay with me.

I don’t paint all Southern leaders with the same broad brush. I know that both Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson didn’t like slavery. I have respect for how Lee conducted himself once he understood the war was lost. He used his reputation to put down the suggestion that the South should continue the conflict through guerrilla warfare. He called for unity.

While I disagree with his decision to join in the rebellion, his personal character can still be admired despite the flaws in his thinking. So I can understand why some want to erect monuments to him. When it comes to character, his is far and above most of those who are now either promoting or protesting any memorial to him.

And the mania for tearing down all monuments relating to the South during the Civil War has gotten out of hand. Protesters in Durham, North Carolina, took matters into their own hands and tore down a statue without any authorization. They constituted a mob, and we don’t have mob rule in America.

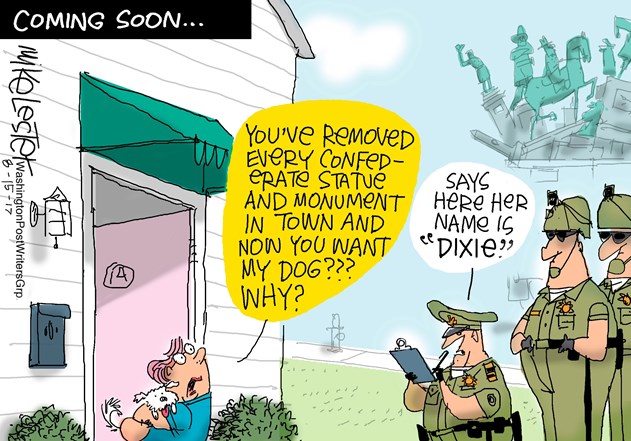

When rational thought is dismissed, where will we end up?

Where do I stand on those Civil War monuments to the South? It depends. If they are simply memorials to those who lost their lives, I have no problem with them. They mark a tragic event in American history. If, however, they are there to celebrate those who openly rebelled against the government, basing their rebellion on how wonderful slavery is and defying the Constitution, I have no problem with their removal, especially due to the horrific memory of slavery and racial prejudice that affects so many today.

It also depends on the location of those monuments. For instance, when I visited the Manassas Battlefield, I took this photo of an iconic statue:

This marks the spot where Thomas Jackson stood like a “stone wall” and rallied his troops in the battle, thereby earning his nickname. It is appropriate to have this statue at this particular spot. It notes a significant historical event. Leave it alone. Learn from it.

So while I’m not a full supporter of keeping all such monuments, neither do I believe it is right to succumb to mobs and allow them to be torn down without regard to the rule of law. Consider each monument and memorial individually and make a decision on each, taking into account whether they advance historical memory in the right manner or if they inflame passions with the wrong emphasis.

There is also the matter of the slippery slope. Some are so exercised against what took place in history that they are beginning to promote the argument that the Founders, because some were slaveholders, ought to have their memory erased from our national consciousness.

Tear down the Jefferson Memorial, some would say. Destroy the Washington Monument. Rub off Mt. Rushmore. It gets silly, but also dangerous to real history. Even though some Founders owned slaves, those who know history also know their consciences bothered them about an institution that existed before they were born and into which they were placed. They thought a lot about how to end that institution because they believed it was detrimental to the nation.

Those who cannot make a distinction between the attitude of the Founders and those who later took up arms to defend slavery are too simplistic in their analysis. In most cases, I fear, analysis is lacking; emotion reigns.

Let’s revisit this issue of which monuments are proper, but do so rationally.