Clyde Kilby was the man responsible for bringing the C. S. Lewis Papers to the Wade Center at Wheaton College, where not only Lewis’s papers now reside, but also those of Tolkien and five other British luminaries with ties to Lewis.

Clyde Kilby was the man responsible for bringing the C. S. Lewis Papers to the Wade Center at Wheaton College, where not only Lewis’s papers now reside, but also those of Tolkien and five other British luminaries with ties to Lewis.

Kilby and Lewis met face-to-face only once, back in 1953, but the impression from that visit stayed with Kilby the rest of his life. When Kilby returned from England, he wrote about his experience.

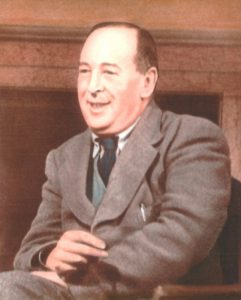

Upon knocking [at Lewis’s Oxford office door], Kilby was greeted warmly by the man who had meant so much to him in writing. First impressions? “He has a pleasant, almost jolly face, full though not fat, with a double chin. He has a high forehead and thinning hair. Actually, he is a much better looking man than the published picture of him.”

Kilby also liked Lewis’s sense of humor, of a type understood best by a fellow academic: “He spoke of the making of a bibliography as just plain labor and laughed about the idea of the scholar’s life as a sedentary one, saying that the physical labor of pulling big folios from the shelves of the Bodleian was all the exercise he needed.”

It was the sharing of minds, though, that stood out to Kilby as he looked back on this meeting. They spoke of the nature of the Renaissance, with Lewis’s comments foreshadowing what he would say the next year in his inaugural lecture at Cambridge. They also talked about Palestine/the new nation of Israel and of Kilby’s recent trip there. Lewis longed for the pleasure of visiting the Holy Land someday, and they speculated about the possible rebuilding of the Jewish temple and the reestablishment of sacrifices on that ancient spot in Jerusalem.

Further, they discussed the relationship between Christian faith and art, as well as all things people consider secular. “He said the same relation existed between Christianity and art as between Christianity and carpentry.” Of course, given Lewis’s penchant for writing novels, they debated the exact nature of that specific species of literature.

Further, they discussed the relationship between Christian faith and art, as well as all things people consider secular. “He said the same relation existed between Christianity and art as between Christianity and carpentry.” Of course, given Lewis’s penchant for writing novels, they debated the exact nature of that specific species of literature.

When Kilby quoted someone who had said a novel is no better than a well-told lie, Lewis objected: “As I expected, he disagreed completely with this claim, saying that one is far more likely to find the truth in a novel than in a newspaper. In fact, he said he had quit reading newspapers because they were so untruthful.”

Kilby also sought to know if Lewis would be lecturing while he was in Oxford. “He said he had no lectures scheduled and bantered me as a college professor wanting to hear a lecture while on vacation. In fact, in all his talk there is an incipient good humor and genuineness that makes a conversation with him a real pleasure.”

The only awkward moment was when Kilby asked him to autograph one of Lewis’s books he had brought with him. Although Lewis agreed to the request, he commented that he saw no sense in doing so. That led Kilby to conclude something about his character: “Both from reading his books and talking with him, I get the impression that he is far more fearful than most of us of the subtle sin of pride and tries in every way to escape it: thus his reticence to give an autograph.”

The only awkward moment was when Kilby asked him to autograph one of Lewis’s books he had brought with him. Although Lewis agreed to the request, he commented that he saw no sense in doing so. That led Kilby to conclude something about his character: “Both from reading his books and talking with him, I get the impression that he is far more fearful than most of us of the subtle sin of pride and tries in every way to escape it: thus his reticence to give an autograph.”

This account of Kilby’s encounter with Lewis is found in my new book on Lewis’s contacts with and influence upon Americans. America Discovers C. S. Lewis: His Profound Impact is currently available at the publisher’s site. It’s coming to Amazon soon. It is replete with such stories, so if you liked this one, I’m sure you’ll like the others also.