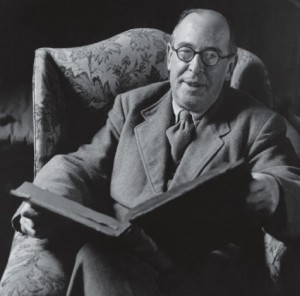

I believe I’ve read most of C. S. Lewis’s essays sometime during my life, but some of them I read so long ago I have forgotten the pearls within. I recently re-read his “Learning in War-Time” reflections as Britain was engaged in WWII and was reminded why others have commented on it so often.

I believe I’ve read most of C. S. Lewis’s essays sometime during my life, but some of them I read so long ago I have forgotten the pearls within. I recently re-read his “Learning in War-Time” reflections as Britain was engaged in WWII and was reminded why others have commented on it so often.

The big question he asks and attempts to answer is why should people continue to be interested in what are considered the normal, routine matters of life when the whole fate of Europe may lie in the balance of the outcome of the war. Why focus on learning, philosophy, history, and similar pursuits when others are sacrificing their lives on the battlefield? “Is it not like fiddling while Rome burns?” he asks.

His response undoubtedly shocked some people when he stated, “The war creates no absolutely new situation; it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it.” Lewis then adds a large dose of common sense:

Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself. If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun.

He doubles down on that premise as he continues:

We are mistaken when we compare war with “normal life.” Life has never been normal. Even those periods which we think most tranquil, like the nineteenth century, turn out, on closer inspection, to be full of crises, alarms, difficulties, emergencies.

As a historian, I can vouch for the accuracy of Lewis’s statement. I’m aware of periods in American history that are usually considered peaceful, but if examined in greater depth, one finds turmoil always bubbling under the surface, if not openly. Lewis further notes,

Plausible reasons have never been lacking for putting off all merely cultural activities until some imminent danger has been averted or some crying injustice put right. But humanity long ago chose to neglect those plausible reasons. They wanted knowledge and beauty now, and would not wait for the suitable moment that never comes.

It is no different for the Christian, Lewis concludes:

An appetite for these things exists in the human mind, and God makes no appetite in vain. We can therefore pursue knowledge as such, and beauty as such, in the sure confidence that by so doing we are either advancing to the vision of God ourselves or indirectly helping others to do so.

I like this splash of reality from Lewis. It’s worth contemplating today.