Why did the Stamp Act, passed by the British government in 1765 and scheduled to go into effect the next year, raise such a furor in the American colonies? What was different about this act and how did they respond to it? As we continue our examination of American history, I will begin to tackle that question today.

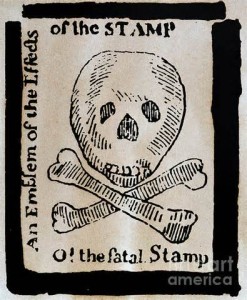

The colonists considered this act poisonous to their liberties. Why?

The colonists considered this act poisonous to their liberties. Why?

The act itself was a tax on all legal documents, newspapers, playing cards, and dice. That, in itself, was bad enough because the tax had to be paid in specie—coins—which was in short supply in the colonies. A lot of commerce was conducted via barter.

Another issue was that enforcement of the act was placed in the hands of special admiralty courts that would have no juries of their peers. This was considered a high-handed action at odds with their rights as British citizens.

But the greatest problem was that this tax had been mandated by Parliament, a novelty in British taxation of the colonies. While the colonists acknowledged the right of Parliament to legislate for the empire overall in matters of international trade, they had their own legislatures to tax them directly. Without any representation in Parliament, they saw this tax as arbitrary, something imposed upon them without their consent, which again was contrary to their rights as citizens of the empire.

The first salvo against the Stamp Act came from Virginia, spurred on by a new member of its House of Burgesses, Patrick Henry.

The first salvo against the Stamp Act came from Virginia, spurred on by a new member of its House of Burgesses, Patrick Henry.

Henry, by the force of his arguments, persuaded a reluctant House to pass a number of resolutions stating opposition to the act. In summary, here is what those resolutions declared:

Colonists have always enjoyed the same liberties as all citizens of the British Empire, as if they were living in Britain itself;

All taxation must be by the people’s own representatives to ensure against burdensome taxes;

Britain has always recognized this right of local lawmaking and taxation.

The final resolution is best put in Henry’s own words:

Resolved, therefore that the General Assembly of this Colony have the only and exclusive Right and Power to lay Taxes and Impositions upon the inhabitants of this Colony and that every Attempt to vest such Power in any person or persons whatsoever other than the General Assembly aforesaid has a manifest Tendency to destroy British as well as American Freedom.

While not fully documented, we are told from some sources that Henry gave a rousing speech at the time that almost led to his censure. He is said to have proclaimed,

While not fully documented, we are told from some sources that Henry gave a rousing speech at the time that almost led to his censure. He is said to have proclaimed,

Caesar had . . . his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third . . .

At this point, there were cries from some of the members that Henry was on the verge of treason because they all knew where he was going with this statement. Caesar had been assassinated in the Roman Senate and Charles I had been beheaded. Henry, reading his audience, finished his statement with the simple warning, “And George the Third may profit by their example.”

After these resolutions passed, Henry wrote down his innermost feelings about the importance of taking this stand:

Whether this will prove a blessing or a curse will depend upon the use our people make of the blessings which a gracious God hath bestowed on us. If they are wise, they will be great and happy. If they are of a contrary character, they will be miserable. Righteousness alone can exalt a nation. Reader! Whoever thou art, remember this; and in thy sphere, practise virtue thyself, and encourage it in others.

Those words are still applicable today.