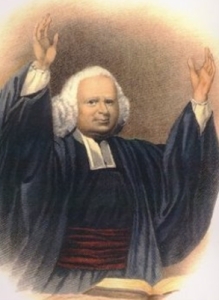

David Garrick, the most popular actor in Britain in the eighteenth century, once remarked, “I would give a hundred guineas if I could say ‘Oh’ like Mr. Whitefield.” He was referring to evangelist George Whitefield, who, at the young age of 25, arrived in the American colonies and became the focal point of the First Great Awakening.

David Garrick, the most popular actor in Britain in the eighteenth century, once remarked, “I would give a hundred guineas if I could say ‘Oh’ like Mr. Whitefield.” He was referring to evangelist George Whitefield, who, at the young age of 25, arrived in the American colonies and became the focal point of the First Great Awakening.

Whitefield was educated at Oxford and became a close friend of John Wesley’s. Together they were part of a student organization called “The Holy Club,” which was dedicated to the disciplines of the Christian life. Converted during his time at Oxford, he was ordained within the Anglican church and spent the rest of his life as an itinerant evangelist, easily, along with Wesley, the most effective voices for the faith in that century.

Whitefield was very dramatic in his preaching, which is why Garrick was so enamored of him. His sermons were like stage plays, entertaining the crowds while communicating the need for spiritual rebirth. The churches were too small to hold the crowds who wanted to hear him, both in England and in America. Sometimes, those outdoor crowds could be raucous and mocking to both Whitefield and Wesley, throwing fruit or whatever was at hand to make fun of them. Yet both continued to preach despite the attempt at persecution. The people’s need for salvation trumped everything.

When Whitefield toured the American colonies throughout 1739-1740, revival followed everywhere in his wake. He struck up a friendship with Benjamin Franklin, who made a number of observations about Whitefield. Amazed at his speaking voice and its projection, Franklin once calculated that, in an open space, 30,000 people would have no trouble hearing him preach. At another time, listening to one of his sermons, Franklin donated some money to the orphanage Whitefield had started in Georgia. As the sermon continued, Franklin felt impressed to donate more. Before it was over, he had emptied his pockets.

After Whitefield left Philadelphia, Franklin remarked that one could not walk down the streets of the city without hearing people singing hymns in their homes. The spiritual tenor of the place had been transformed.

Whitefield and Wesley parted ways theologically, with Wesley a confirmed Arminian and Whitefield a Calvinist, yet they remained friends. Whitefield’s Calvinism, though, took a back seat to the practicality of his preaching. As Jonathan Edwards’s wife Sarah, who heard Whitefield preach when he came to Massachusetts to join with Edwards, remarked, “He makes less of the doctrines than our American preachers generally do and aims more at affecting the heart. He is a born orator. A prejudiced person, I know, might say that this is all theatrical artifice and display, but not so will anyone think who has seen and known him.”

According to historian Paul Johnson, Whitefield, during his lifetime, was conceivably the one man known by nearly everyone in all the colonies. Johnson rates his popularity on a par with George Washington. Yet how many people today know of Whitefield?

He was 55 when he returned to America for the last time in 1770. His health was failing. A friend told him he was more fit to go to bed than to preach. Whitefield agreed, but said emphatically that he would rather wear out than rust out. He was in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and nearly unable to stand, but once he started his sermon, his strength returned. Afterwards, at the pastor’s residence where he was staying, he was going up to bed, only to be asked by a crowd to speak to them again. He obliged, then went to bed. Whitefield died at dawn that next morning.

George Whitefield was a man wholly devoted to carrying out the task God had given him. He deserves to be remembered, and his life should be an inspiration for those of us who seek to do what God has called us to do in our day.