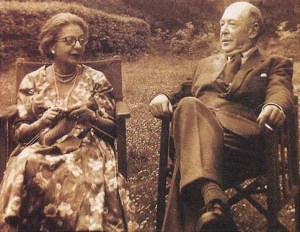

Going through the letters of C. S. Lewis, I reached, this week, the time in 1960 when his wife, Joy, died. After a two-year cancer hiatus, the disease came back in full force throughout her bones. Lewis always knew this could happen. In 1957, after the laying on of hands and prayer, she made a miraculous recovery (even the doctors admitted as much). Yet both she and Lewis knew this might not be a permanent thing, that perhaps God was giving them more time to develop their new marriage.

Going through the letters of C. S. Lewis, I reached, this week, the time in 1960 when his wife, Joy, died. After a two-year cancer hiatus, the disease came back in full force throughout her bones. Lewis always knew this could happen. In 1957, after the laying on of hands and prayer, she made a miraculous recovery (even the doctors admitted as much). Yet both she and Lewis knew this might not be a permanent thing, that perhaps God was giving them more time to develop their new marriage.

In four of his letters from 1960, we see the progression of this thinking and how he tried to work through the bad news of the cancer’s return and, ultimately, Joy’s death.

On April 16, he wrote to one of his former students, Sheldon Vanauken, an American who had studied at Oxford and whom Lewis had helped lead to the faith, and who had suffered the loss of his wife also. Vanauken’s story is found in his autobiographical A Severe Mercy, a book I highly recommend. In this letter, Lewis says,

You must pray for me now. Joy’s cancer has returned and the doctors hold out no hope. Of course this is irrelevant to the question whether the previous recovery was miraculous. There can be miraculous reprieve as well as miraculous pardon, and Lazarus was raised from the dead to die again.

The return of the cancer did not, in Lewis’s mind, negate the wonderful recovery of the previous two years. His use of Lazarus as an example, I think, is quite appropriate. How many of us have every thought about Lazarus’s later life and the fact that he had to go through death once more? All physical healing is temporary anyway. Our true life lies in eternity.

Joy died on July 13. Two days later, Lewis wrote a short note to Vera Gebbert, one of his long-time American correspondents:

Alas, you will never send anything “for the three of us” again, for my dear Joy is dead. Until within ten days of the end we hoped, although noticing her increasing weakness, that she was going to hold her own, but it was not to be. . . .

I could not wish that she had lived, for the cancer had attacked the spine, which might have meant several days of suffering, and that she was mercifully spared. You will understand that I have no heart to write more, but I hope when next I send a letter it will be a less depressing one.

Caught up in the numbness of her recent death, he still can be thankful that she was spared even greater suffering.

Two months later, he tried to describe his journey to Mary Willis Shelburne, another of his American friends:

As to how I take sorrow, the answer is “In nearly all the possible ways.” Because, as you probably know, it isn’t a state but a process. It keeps on changing—like a winding road with quite a new landscape at each bend. Two curious discoveries I have made. The moments at which you call most desperately and clamorously to God for help are precisely those when you seem to get none. And the moments at which I feel nearest to Joy are precisely those when I mourn her least. Very queer. In both cases a clamorous need seems to shut one off from the thing needed. No one ever told me this. It is almost like “Don’t knock and it shall be opened to you.” I must think it over.

He was grappling with the loss, and trying to understand the ways of God in its wake. For a fuller account of how Lewis ultimately came to an understanding, read his poignant and searing little book A Grief Observed.

Three months after losing Joy, he wrote to Chad Walsh and his wife. Walsh was an American professor who had written the first analytical book about Lewis back in the 1940s—C. S. Lewis: Apostle to the Skeptics. Here we see the balance:

I knew without being told how you would both feel about Joy’s death. What I did not know was the touching fact that our joint happiness had added something to your own. It was a wonderful marriage. Even after all hope was gone, even on the last night before her death, there were “patins of bright gold.” Two of the last things she said were “You have made me happy” and “I am at peace with God.”

Wouldn’t we all like to end our lives that way, with two sterling testimonies? To look at a loved one and say “You have made me happy” is a wonderful testimony for this earthly life; to say “I am at peace with God” is the entrance to an eternal joy.