Thus far, in my examination of the Puritans’ role in American history, I’ve emphasized their original intent—to be a City on a Hill, an example of a Christian community—and their contributions to American government—the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut and the Massachusetts Body of Liberties.

Those are all positive elements of the Puritan heritage. I want to delve now into some of the controversies of the era.

It’s one thing to have a beautiful dream of unity, but reality always intrudes. The Massachusetts authorities soon found themselves faced with threats to their original vision.

The first real threat came from one of their ministers, Roger Williams. Although ostensibly part of the Puritan migration that sought to control the direction of the Anglican church, Williams was more attuned with the separatist movement.

The first real threat came from one of their ministers, Roger Williams. Although ostensibly part of the Puritan migration that sought to control the direction of the Anglican church, Williams was more attuned with the separatist movement.

He took a post as associate minister of the church in Salem. From that position, he began proclaiming certain beliefs that could have undermined the entire Puritan enterprise. Williams taught the following:

- The Puritan churches were being unfaithful to God by not disassociating themselves from the Anglican church.

- It was sinful to take any kind of oath, even in a court of law.

- The land they were on belonged to the natives, so the king had no right to grant it to the Massachusetts Company.

Puritan authorities were stunned by Williams’s claims. First, it never was their intent to break away from the Anglican church, but to change it from within. If word got back to England that there was a movement afoot in this new colony to break away, their charter might be recalled.

Second, Williams’s insistence that no oath be used could seriously damage the administration of justice. They firmly believed it was important to make a witness swear an oath before God. To perjure oneself in court was then tantamount to lying to God, and their society took that sin seriously.

Third, to say they had no right to settle there was to possibly jeopardize the colony’s existence. Not every acre of ground was inhabited by the natives. As far as they knew, they hadn’t driven any tribe off its land.

Under pressure, Williams left Massachusetts for a while and lived among the separatist Pilgrims in Plymouth. But even there, he caused controversy. He concluded they weren’t separatist enough, so he eventually returned to Salem and continued to spread his message.

The authorities felt this could not be tolerated and warned Williams to stop. He refused. They then put him on trial for sedition—speaking with the intent to destroy the government—found him guilty and banished him.

The first thing to note here is that the punishment was simply, “Hey, Roger, you need to go somewhere else, and we’ll help you by forcing you to leave.” He was not tortured to change his views; he was not summarily executed for his controversial beliefs; he was only told he had to find another place to live. And there was an entire continent before him.

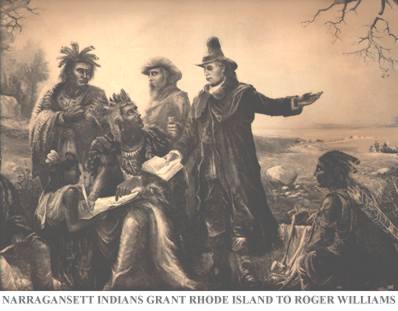

What happened eventually was that Williams moved south and negotiated a purchase of land with the Narragansett tribe, a place he called Providence Plantations, and that we today call Rhode Island.

Williams is normally celebrated in modern histories as a torchbearer of religious liberty, since Rhode Island became a place without an official church and people were allowed to believe according to conscience. Yet it’s kind of ironic that Williams himself was kicked out of Massachusetts for being too dogmatic in his own beliefs. He ultimately came to the conclusion that he couldn’t force anyone to adopt his views, so he allowed complete liberty.

Were the Puritans wrong in their judgment? Well, that’s a judgment call. Williams’s strident beliefs really could have destroyed the colony if the majority had adopted them. They felt they had a solid reason for banishing him.

Roger Williams, though, was only the first test of the Puritans’ City on a Hill. Another one came soon after in the form of a woman named Anne Hutchinson. She will be the topic of my next Puritan post.