As I noted yesterday, I’m in Virginia, showing students some of the most significant historical sites of early America. On Sunday, we visited one of the hidden treasures of early American history,Berkeley Plantation, located about thirty miles outside Williamsburg. It’s in Charles City County, which has absolutely no real towns or cities within it. That’s on purpose. They’re attempting to keep the rural nature of the area. The county, though, is replete with plantations. None, in my view, is more connected to the entire gamut of American history from the founding of Virginia through the Civil War than Berkeley.

As I noted yesterday, I’m in Virginia, showing students some of the most significant historical sites of early America. On Sunday, we visited one of the hidden treasures of early American history,Berkeley Plantation, located about thirty miles outside Williamsburg. It’s in Charles City County, which has absolutely no real towns or cities within it. That’s on purpose. They’re attempting to keep the rural nature of the area. The county, though, is replete with plantations. None, in my view, is more connected to the entire gamut of American history from the founding of Virginia through the Civil War than Berkeley.

The site’s entrance into the mainstream of colonial history begins prior to the building of the house. It was one of the first settlements outside of Jamestown as colonists began to spread upriver.

Upon arrival at this site, the English adventurers followed their instructions to the letter: they were told to hold a thanksgiving service immediately, which they did. This was in 1619, one year before the Pilgrims arrived in New England. The plantation commemorates that first thanksgiving with a shrine down by the river where it took place.

Upon arrival at this site, the English adventurers followed their instructions to the letter: they were told to hold a thanksgiving service immediately, which they did. This was in 1619, one year before the Pilgrims arrived in New England. The plantation commemorates that first thanksgiving with a shrine down by the river where it took place.

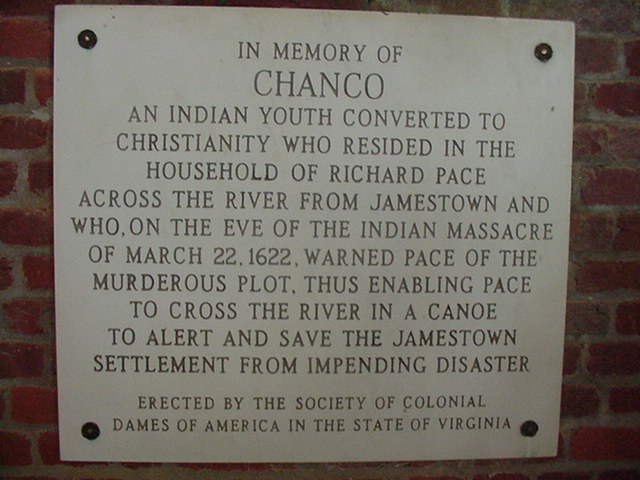

This early settlement was wiped out in the 1622 Massacre when the Powhatan Indians rose up and tried to kill all Englishmen in Virginia. They were unsuccessful, but the damage was great, with nearly one-third of the settlers murdered. Jamestown itself was spared the worst of the attack, having been warned by an Indian who had become a Christian. His name was Chanco, and he is memorialized in the church at Jamestown with the following plaque:

The Harrison family bought the property at Berkeley in the 1690s and constructed the first shipyard in the New World. Later, in the 1720s, Benjamin Harrison IV built the house that stands there still today. If you look at the side of the house, you can see an inscription in the wall:

It is difficult to read from this distance—it’s as close as I could get—but it has an “H” at the top for Harrison, a “B” on the left side for Benjamin, and an “A” on the right side for Anne, his wife. Between the letters is a heart, indicating the love they had for one another. A touch of humanity in the middle of the bricks.

Benjamin Harrison VI was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. His son, William Henry Harrison, was a renowned general who won the Battle of Tippecanoe and served in the War of 1812. He later won the presidency in 1840 and returned to this house to write his inaugural address. Unfortunately, one month after delivering it, he died of pneumonia, making his the shortest presidency in American history.

The plantation came to the forefront again during the Civil War. Gen. George McClellan used it as his headquarters in 1862 in his unsuccessful attempt to take Richmond. While the army camped there, it was reviewed by President Lincoln. Another interesting claim to fame is that “Taps” was composed there at that time and first played to the troops. We now use “Taps” at flag ceremonies and at military funerals.

Although not directly connected to Berkeley, the Harrison family didn’t disappear from influence: William Henry Harrison’s grandson—another Benjamin Harrison, became the 23rd president, elected in 1888.

History comes alive at Berkeley Plantation.