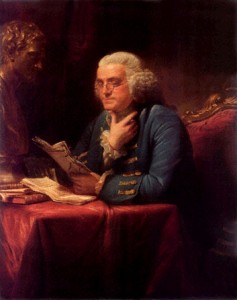

When dealing with the religious beliefs of America’s Founding Generation—those who participated in the Revolution and the creation of the Constitution—one must draw a clear distinction between those who were genuine Christians and those who were merely religious in a general sense. As I tell my students incessantly, early America was a society built on a Biblical framework of thinking, even though some of the prominent individuals may not have been what evangelicals call “born again.” Yesterday’s post dealt with Jefferson. Today I’d like to focus on Benjamin Franklin.

At the Continental Congress, Franklin and Jefferson were placed on a committee to try to come up with an official seal for the new United States. Interestingly, here was their proposal:

For both Jefferson and Franklin, apparently nothing would make the point better than comparing America’s situation with the Israelites fleeing from Pharaoh. The seal shows Pharaoh [read: George III] drowning in the Red Sea by the providential hand of God.

Franklin, at the Constitutional Convention, famously made an appeal to the assembled delegates when they seemed to be at cross purposes and the convention was on the verge of failure. At that crucial point, he reminded them of something:

Franklin, at the Constitutional Convention, famously made an appeal to the assembled delegates when they seemed to be at cross purposes and the convention was on the verge of failure. At that crucial point, he reminded them of something:

The longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth: “that God governs in the affairs of men.”And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid? We have been assured … in the sacred writings that except the Lord build the house, they labor in vain that build it. I firmly believe this.

These two instances—the devising of the seal and the appeal to look to God—show that Franklin operated within the Biblical milieu that dominated the times. But what of his personal faith in Jesus Christ?

On March 9, 1790, Franklin sent a letter to Ezra Stiles, the president of Yale. Stiles had asked about Franklin’s views of Jesus. In his response, the 85-year-old Founder commented,

As to Jesus of Nazareth, my Opinion of whom you particularly desire, I think the System of Morals and his Religion as he left them to us, the best the World ever saw, or is likely to see; but I apprehend it has received various corrupting Changes, and I have with most of the present Dissenters in England, some Doubts as to his Divinity: tho’ it is a Question I do not dogmatise upon, having never studied it, and I think it needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an Opportunity of knowing the Truth with less Trouble.

If you read yesterday’s post on Jefferson, you see a similarity here. Franklin believed that those who wrote the New Testament embellished upon who Jesus was. He mentions dissenters in England, by which he undoubtedly means the Unitarians, who rejected the idea of the Trinity. For me, the saddest part of this letter is that last line. He doesn’t even want to check into the matter further because he expects very soon to know the truth for sure—he knew he was ailing and would not be around much longer. He was right. Franklin died one month after penning this letter.

That’s not the best way to find the truth. By then, it’s too late.