I keep writing my C. S. Lewis book. The chapter I’m currently working on highlights some of the regular American correspondents Lewis had for the last decade and half of his life. Warfield M. Firor was one of those. He was fairly famous as a neurosurgeon at Johns Hopkins. A Chair in Surgery has been established there in his name.

I keep writing my C. S. Lewis book. The chapter I’m currently working on highlights some of the regular American correspondents Lewis had for the last decade and half of his life. Warfield M. Firor was one of those. He was fairly famous as a neurosurgeon at Johns Hopkins. A Chair in Surgery has been established there in his name.

Firor, after WWII, was not only an admirer of Lewis’s books, but one of his most faithful contributors during the rationing after the war. He sent a steady stream of packages with a variety of foods that the English had trouble obtaining. Firor was particularly notable for sending over hams, one of Lewis’s favorite meats, but scarce for many years. Those hams started appearing in late 1947. After the arrival of the first one, Lewis replied,

I am completely at a loss when it comes to thanking you for your last parcel: because I rather doubt if you know what you have done. A ham such as you sent lifts me up into our millionaire class. Such a thing couldn’t be got on this side unless one was very deep in the Black Market. . . .

And as for the cheese, I found I’d almost forgotten what real cheese tastes like.

I and all my friends are very deeply grateful; you have given an amount of pleasure which you, in your happier country, cannot realize. . . .

P.S. We’re boiling it tomorrow. Meantime I go and have a look at it every now and then for the mere beauty of it: the finest view in England.

A scant three months later, Lewis had to send another thank-you letter, telling Firor, “No one ever sees a ham these days over here, and even in a good restaurant it is very rarely that you would get a small slice of ham. I shall probably be known in Oxford for months as ‘the man who got the ham from America!’ Believe me, I am heartily thankful to you for your kindness.”

When another one arrived just two months later, Lewis informed Firor, “The arrival of that magnificent ham leaves me just not knowing what to say. If it were known that it was in my house, it would draw every housebreaker in the neighbourhood more surely than would a collection of gold plate! Even in your favoured country its intrinsic value must have been considerable, and over here it is beyond valuing.”

Lewis decided to share this largesse with the Inklings, rather than hoard it all for himself. He described to Firor what transpired at their last meeting:

Lewis decided to share this largesse with the Inklings, rather than hoard it all for himself. He described to Firor what transpired at their last meeting:

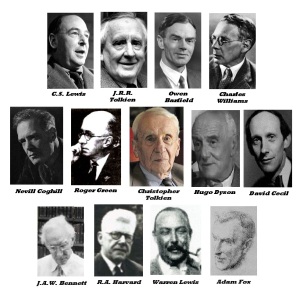

The fate of the ham was this: we have a small informal literary club which meets in my rooms every Thursday for beer and talk, and “in happier times” for an occasional dinner. And last night, having your ham to dine off, we had a meal which eight members attended. By diligent “scraping the bottom of the barrel” in various colleges we got two bottles of burgundy and two of port: the college kitchen supplied soup, fish and a savoury: and we had a delightful evening. This by English standards is a banquet rarely met with, and all agreed that they hadn’t eaten such a dinner for five years or more.

Attached to the letter was a “Ham Testimonial” signed by all the Inklings who were present that evening to enjoy the feast. So Firor had a testimonial signed not only by Lewis but by J. R. R. Tolkien. Imagine what a price that would fetch today.

My study of Lewis has yielded so many fascinating insights. I’m grateful for this sabbatical year when I can devote myself to this.