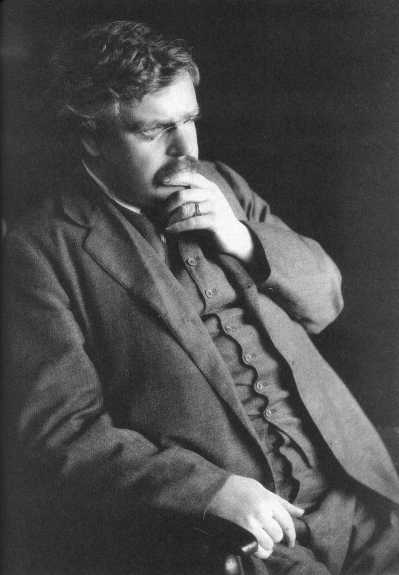

Great Quotes By: G. K. CHESTERTON

From Autobiography:

I was brought up among people who were Unitarians and Universalists, but who were well aware that a great many people around them were becoming agnostics or even atheists.One half [of them] were arguing that, because God was in His heaven, all must be right with the world; with this world or with the next. The other half of them were specially bent on showing that it was very doubtful if there was any God in any heaven, and that it was so certain to the scientific eye that all is not right with the world, that it would be nearer the truth to say that all is wrong with the world.

In Father Brown, it was the chief feature to be featureless. The point of him was to appear pointless; and one might say that his conspicuous quality was not being conspicuous. His commonplace exterior was meant to contrast with his unsuspected vigilance and intelligence; and that being so, I made his appearance shabby and shapeless, his face round and expressionless, his manners clumsy, and so on.

I do not wish my remarks confused with the horrible and degrading heresy that our minds are merely manufactured by accidental conditions, and therefore have no ultimate relation to truth at all. With all possible apologies to the freethinkers, I still propose to hold myself free to think. And anybody who will think for two minutes will see that this thought is the end of all thinking. It is useless to argue at all, if all our conclusions are warped by our conditions. Nobody can correct anybody’s bias if all mind is all bias.

A [man] once remarked to me: “There must be something rottenly wrong with education itself. So many people have wonderful children and all the grown-up people are such duds.” And I know what he meant, though I am in doubt whether my present duddishness is due to education or to some deeper and more mysterious cause.

A defendant does not properly mean a person defending other things. It means a person defending himself; and I should be the last to defend anything so indefensible.

The Intelligentsia of the artistic and vaguely anarchic clubs was indeed a very strange world. And the strangest thing about it, I fancy, was that, while it thought a great deal about thinking, it did not think. A large section of the Intelligentsia seemed wholly devoid of Intelligence. As was perhaps natural, those who pontificated most pompously were often the most windy and hollow.

On the whole, I think I owe my success to having listened respectfully and rather bashfully to the very best advice, given by all the best journalists who had achieved the best sort of success in journalism; and then going away and doing the exact opposite.

The first thing to note, as typical of the modern tone, is a certain effect of toleration which actually results in timidity. Religious liberty might be supposed to mean that everybody is free to discuss religion. In practice it means that hardly anybody is allowed to mention it.

[Re: a friend who collected miniature objects] My wife happens to have the same hobby of collecting tiny things as toys; though some have charged her with inconsistency on the occasion when she collected a husband.

My last American tour consisted of inflicting no less than ninety lectures on people who never did me any harm.

There is a sort of fireside fairytale, more fitted for the hearth than for the altar; and in that what is called Nature can be a sort of fairy godmother. But there can only be fairy godmothers because there are godmothers; and there can only be godmothers because there is God.

From Heretics:

In former days, the heretic was proud of not being a heretic. But a few modern phrases have made him boast of it. He says, with a conscious laugh, “I suppose I am very heretical,” and looks around for applause. The word “heresy” not only means no longer being wrong; it practically means being clear-headed and courageous. The word “orthodoxy” not only no longer means being right; it practically means being wrong.

It is foolish, generally speaking, for a philosopher to set fire to another philosopher … because they do not agree on their theory of the universe. That was done very frequently in the last decadence of the Middle Ages, and it failed altogether in its object. But there is one thing that is infinitely more absurd and unpractical than burning a man for his philosophy. This is the habit of saying that his philosophy does not matter, and this is done universally in the twentieth century, in the decadence of the great revolutionary period.

The theory of the un-morality of art has established itself firmly in the strictly artistic classes. They are free to produce anything they like. They are free to write a Paradise Lost in which Satan shall conquer God. They are free to write a Divine Comedy in which heaven shall be under the floor of hell. But if it was a chief claim of religion that it spoke plainly about evil, it was the chief claim of all that it spoke plainly about good. The thing that is resented in that great modern literature is that, while the eye that can perceive what are the wrong things increases in an uncanny and devouring clarity, the eye that sees what things are right is growing mistier and mistier every moment, till it goes almost blind with doubt.

Every one of the popular modern phrases and ideals is a dodge in order to shirk the problem of what is good. We are fond of talking about “liberty”; that, as we talk of it, is a dodge to avoid discussing what is good. We are fond of talking about “progress”; that is a dodge to avoid discussing what is good. We are fond of talking about “education”; that is a dodge to avoid discussing what is good.

When he drops one doctrine after another in a refined skepticism, when he declines to tie himself to a system, when he says that he has outgrown definitions, when he says that he disbelieves in finality, when, in his own imagination, he sits as God, holding no form of creed but contemplating all then he is by that very process sinking slowly backwards into the vagueness of the vagrant animals and the unconsciousness of the grass. Trees have no dogmas. Turnips are singularly broad-minded.

From Orthodoxy

I freely confess all the idiotic ambitions of the end of the 19th century. I did, like all other solemn little boys, try to be in advance of the age. Like them I tried to be some ten minutes in advance of the truth. And I found that I was eighteen hundred years behind it.

A man was meant to be doubtful about himself, but undoubting about the truth; this has been exactly reversed. Nowadays the part of a man that a man does assert is exactly the part he ought not to assert—himself. The part he doubts is exactly the part he ought not to doubt—the Divine Reason.

That peril is that the human intellect is free to destroy itself. Just as one generation could prevent the very existence of the next generation, by all entering a monastery or jumping into the sea, so one set of thinkers can in some degree prevent further thinking by teaching the next generation that there is no validity in any human thought.

Because children have abounding vitality, because they are in spirit fierce and free, therefore they want things repeated and unchanged. They always say, “Do it again”; and the grown-up person does it again until he is nearly dead. For grown-up people are not strong enough to exult in monotony. But perhaps God is strong enough to exult in monotony. It is possible that God says every morning, “Do it again” to the sun; and every evening, “Do it again” to the moon. It may not be automatic necessity that makes all daisies alike; it may be that God makes every daisy separately, but has never got tired of making them. It may be that He has the eternal appetite of infancy; for we have sinned and grown old, and our Father is younger than we.

According to most philosophers, God in making the world enslaved it. According to Christianity, in making it, He set it free. God had written, not so much a poem, but rather a play; a play he had planned as perfect, but which had necessarily been left to human actors and stage-managers, who had since made a great mess of it.

We have said we must be fond of this world, even in order to change it. We now add that we must be fond of another world (real or imaginary) in order to have something to change it to.

Christendom has excelled in the narrative romance exactly because it has insisted on theological free-will. This is the real objection to that torrent of modern talk about treating crime as disease, about making a prison merely a hygienic environment like a hospital, of healing sin by slow scientific methods. The fallacy of the whole thing is that evil is a matter of choice whereas disease is not.

From The Everlasting Man

It is stark hypocrisy to pretend that nine-tenths of the higher critics and scientific evolutionists and professors of comparative religion are in the least impartial. I do not pretend to be impartial … but I do profess to be a great deal more impartial than they are; in the sense that I can tell the story fairly, with some sort of imaginative justice to all sides; and they cannot.

Today all our novels and newspapers will be found swarming with numberless allusions to a popular character called a Cave-Man. So far as I can understand, his chief occupation in life was knocking his wife about. I have never happened to come upon the evidence for this idea; and I do not know on what primitive diaries or prehistoric divorce-reports it is founded. The cave-man as commonly presented to us is simply a myth or rather a muddle; for a myth has at least an imaginative outline of truth. The whole of the current way of talking is simply a confusion and a misunderstanding, founded on no sort of scientific evidence.

The other day a scientific summary of the state of a prehistoric tribe began confidently with the words “They wore no clothes.” Not one reader in a hundred probably stopped to ask himself how we should come to know whether clothes had once been worn by people of whom everything has perished except a few chips of bone and stone. It was doubtless hoped that we should find a stone hat as well as a stone hatchet. It was evidently anticipated that we might discover an everlasting pair of trousers of the same substance as the everlasting rock.

The dawn of history reveals a humanity already civilized. Perhaps it reveals a civilization already old. And among other more important things, it reveals the folly of most of the generalizations about the previous and unknown period when it was really young. The first two human societies of which we have any reliable and detailed record are Babylon and Egypt. It has appeared to a good many intelligent and well-informed people quite as probable that the experience of the savages has been that of a decline from civilization.

According to the real records available, barbarism and civilization were not successive states in the progress of the world. They were conditions that existed side by side, as they still exist side by side. There were civilizations then as there are civilizations now; there are savages now as there were savages then.

They are obsessed by their evolutionary monomania that every great thing grows from a seed or something smaller than itself. They seem to forget that every seed comes from a tree, or something larger than itself. Now there is very good ground for guessing that religion did not originally come from some detail that was forgotten because it was too small to be traced. Much more probably it was an idea that was abandoned because it was too large to be managed. There is very good reason to suppose that many people did begin with the simple but overwhelming idea of one God who governs all, and afterwards fell away into such things as demon-worship almost as a sort of secret dissipation.

The rivers of mythology and philosophy run parallel and do not mingle till they meet in the sea of Christendom. Simple secularists still talk as if the Church had introduced a sort of schism between reason and religion. The truth is that the Church was actually the first thing that ever tried to combine reason and religion. There had never before been any such union of the priests and the philosophers.

It may be reasonable enough [to] say the Spaniards were sinful, but why in the world say that the South Americans were sinless? Why [suppose] that continent to be exclusively populated by archangels or saints perfect in heaven? There has been a habit of always siding against the Europeans, and representing the rival civilization as sinless, when its sins were obviously crying or rather screaming to heaven. The Christian is only worse because it is his business to be better.

Philosophy began to be a joke; it also began to be a bore. That unnatural simplification of everything into one system or another revealed at once its finality and its futility. Everything was virtue or everything was happiness or everything was fate or everything was good or everything was bad. Anyhow, everything was everything and there was no more to be said. So they said it. Everywhere the sages had degenerated into sophists; that is, into hired rhetoricians or askers of riddles.

Aquinas could understand the most logical parts of Aristotle; it is doubtful if Aristotle could have understood the most mystical parts of Aquinas. Even where we can hardly call the Christian greater, we are forced to call him larger. But it is so to whatever philosophy or heresy or modern movement we may turn.

No other story, no pagan legend or philosophical anecdote or historical event, does in fact affect any of us with that peculiar and even poignant impression produced on us by the word Bethlehem. The truth is that there is a quite peculiar and individual character about the hold of this story on human nature; it is not in its psychological substance at all like a mere legend or the life of a great man.

From first to last the most definite fact is that he is going to die. No two things could possibly be more different than the death of Socrates and the death of Christ. On the third day the friends of Christ coming at daybreak to the place found the grave empty and the stone rolled away. In varying ways they realized the new wonder; but even they hardly realized that the world had died in the night. What they were looking at was the first day of a new creation, with a new heaven and a new earth, and in the semblance of the gardener God walked again in the garden, in the cool not of the evening but the dawn.

It is nonsense to say that the Christian faith appeared in a simple age; in the sense of an unlettered and gullible age. It is equally nonsense to say that the Christian faith was a simple thing; in the sense of a vague or childish or merely instinctive thing. The Church had to be both Roman and Greek and Jewish and African and Asiatic. In the very words of the Apostle of the Gentiles, it was indeed all things to all men.

Other Chesterton Quotes

The terrible danger in the heart of our Society is that the tests are giving way. We are altering, not the evils, but the standards of good by which alone evils can be detected and defined. Men do not differ much about what things they will call evils; they differ enormously about what evils they will call excusable.

Some say religion is the opium of the people. I should say irreligion is the opium of the people. I should say that, in every fact and phase of history, religion had been necessary as the stimulant of the people.

If the novel maxim “religion is a private matter” means that the conviction held in the soul cannot be applied to the society, it means manifest and raving nonsense.

Right is right, even if nobody does it. Wrong is wrong, even if everybody is wrong about it.

A man making experiments in chemistry must expect chemical explosions, and a man making experiments in ethics must expect ethical explosions.

When all are sexless there will be equality. There will be no women and no men. There will be but a fraternity, free and equal. The only consoling thought is that it will endure but for one generation.

Ten million young women rose to their feet with the cry, We will not be dictated to: and proceeded to become stenographers.

We shall soon be in a world in which a man may be howled down for saying that two and two make four, in which people will persecute the heresy of calling a triangle a three-sided figure, and hang a man for maddening a mob with the news that grass is green.

I do believe in Christianity, and my impression is that a system must be divine which has survived so much insane mismanagement.

I am a vegetarian between meals.

Selected by Dr. Alan Snyder