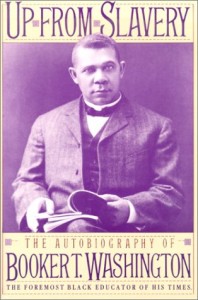

I’ve been reading the autobiography of Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery. The story of his childhood in slavery, the privations he suffered both under slavery and in the years after its abolition, would have made many men bitter. Washington, though, never lost the vision planted in him by God that someday he would be able to rise above it. He learned, along the way, that one’s goal was not to be selfishly motivated but to become the best for the benefit of others.

I’ve been reading the autobiography of Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery. The story of his childhood in slavery, the privations he suffered both under slavery and in the years after its abolition, would have made many men bitter. Washington, though, never lost the vision planted in him by God that someday he would be able to rise above it. He learned, along the way, that one’s goal was not to be selfishly motivated but to become the best for the benefit of others.

Although he experienced racism, he also saw models of true Christian devotion and love in white people who came into the South to help after the Civil War. His time at the Hampton Institute, getting a college education, was the most formative time in his life. The man who established Hampton made a lifelong impression on Washington, as he explains,

I have spoken of the impression that was made upon me by the buildings and general appearance of the Hampton Institute, but I have not spoken of that which made the greatest and most lasting impression on me, and that was a great man—the noblest, rarest human being that it has ever been my privilege to meet. I refer to the late General Samuel C. Armstrong.

It has been my fortune to meet personally many of what are called great characters, both in Europe and America, but I do not hesitate to say that I never met any man who, in my estimation, was the equal of General Armstrong. . . . It was my privilege to know the General personally from the time I entered Hampton till he died, and the more I saw of him the greater he grew in my estimation. One might have removed from Hampton all the buildings, class-rooms, teachers, and industries, and given the men and women there the opportunity of coming into daily contact with General Armstrong, and that alone would have been a liberal education.

Washington learned at Hampton that head knowledge, by itself, was not enough. The emphasis was on character-building and hard work rather than looking to others to provide for oneself. He saw a basic flaw in some of the expectations of his newly freed race:

The ambition to secure an education was most praiseworthy and encouraging. The idea, however, was too prevalent that, as soon as one secured a little education, in some unexplainable way he would be free from most of the hardships of the world, and, at any rate, could live without manual labor. There was a further feeling that a knowledge, however little, of the Greek and Latin languages would make one a very superior human being, something bordering almost on the supernatural.

That’s why, when he started the Tuskegee Institute after he left Hampton, he required all students to take part in manual labor. He was just as concerned for the development of their character as their minds. The two had to go together.

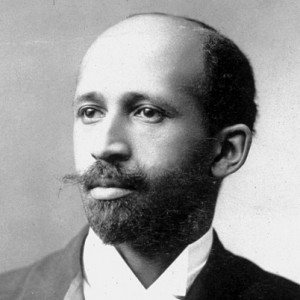

Unfortunately, Washington is not held up today as a role model. Instead, the image of W.E.B. DuBois is the current hero from this era because he stressed the political side. Yet, interestingly, DuBois never had been a slave, had grown up in the northeast where he was largely accepted as part of the community, enjoyed the privilege of a Harvard education and a stint overseas to learn the ways of Europe. He was hardly the typical black man of the period. Despite all these advantages, DuBois became a bitter man, criticizing Washington’s character-centered approach. He instead focused on the top 10% of his race, believing that progress would be made via higher education alone, without the manual labor aspect of Washington’s regimen. DuBois rejected Christian faith, became increasingly bitter over time, and eventually joined the Communist party.

Unfortunately, Washington is not held up today as a role model. Instead, the image of W.E.B. DuBois is the current hero from this era because he stressed the political side. Yet, interestingly, DuBois never had been a slave, had grown up in the northeast where he was largely accepted as part of the community, enjoyed the privilege of a Harvard education and a stint overseas to learn the ways of Europe. He was hardly the typical black man of the period. Despite all these advantages, DuBois became a bitter man, criticizing Washington’s character-centered approach. He instead focused on the top 10% of his race, believing that progress would be made via higher education alone, without the manual labor aspect of Washington’s regimen. DuBois rejected Christian faith, became increasingly bitter over time, and eventually joined the Communist party.

What a shame that DuBois gets more attention nowadays than Booker T. Washington. We need an army of Washingtons in our time, dedicated to humility, gratitude, integrity, and hard work. The victimization mentality must disappear from all races if we are to make genuine progress.