I’ve been teaching a special class at my church on C. S. Lewis. We meet every Monday evening (both in person and on Zoom) to cover some of Lewis’s most thoughtful discourses on life, death, and eternity. My opening slide for the class revealed what we were going to read.

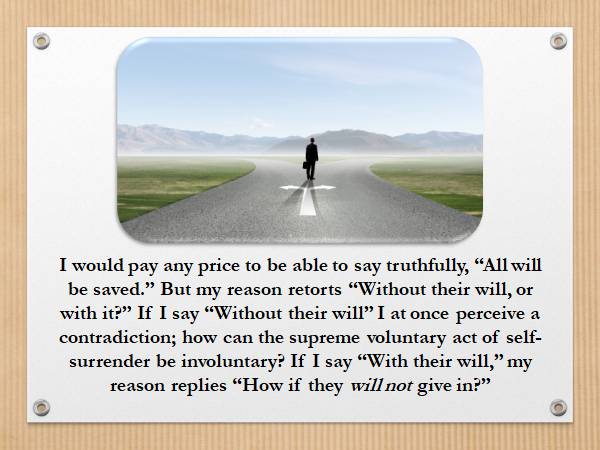

We’ve concluded our discussion of Surprised by Joy and just this past Monday finished key chapters in The Problem of Pain. The most jarring and challenging was the chapter on hell, a subject that the world wants to avoid or mock, depending on one’s perspective, but also one that Christians don’t like to talk about much. Lewis acknowledges that reluctance. After all, why would we who believe it is clearly a Biblical truth, want to fill our thoughts with the awfulness that awaits those who continue in rebellion against a loving God? Yet there’s this thing called choice—free will—that cannot be dismissed. As Lewis notes,

We can say no to the omnipotent Creator. We can say no to His offer of forgiveness and reconciliation. We can continue in stubbornness and excuse-making.

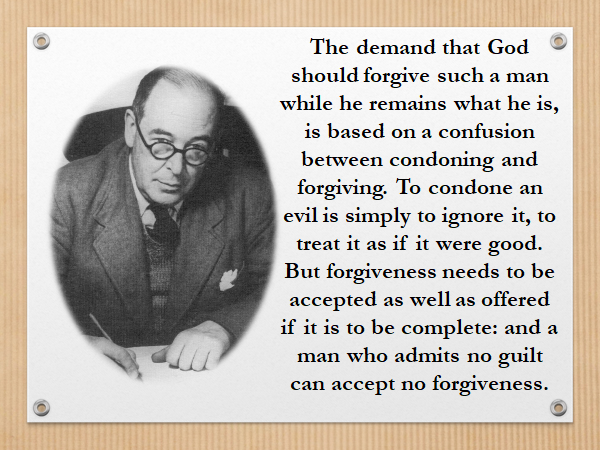

Mankind is adept at denying guilt. In the very same chapter of the Gospel of John where Jesus tells us that God so loved the world that He sent His Son to give us eternal life, and where we are informed that the motive of the Father’s heart is that Jesus was given to us, not to condemn that world but that through Him the world might be saved, we nevertheless are told this:

Mankind doesn’t want its evil deeds to be exposed. Men love the darkness, and they hate the Light/Jesus, because to accept His truth would mean their deeds would become manifest to all. Their pride cannot allow that. They seek to be the masters of their own lives. Lewis, in Surprised by Joy, wrote that before his conversion he considered God to be the great Interferer; he wanted no one to tell him what he had to do. He wanted his life to be wholly his own and not be accountable to another, especially the ultimate Another.

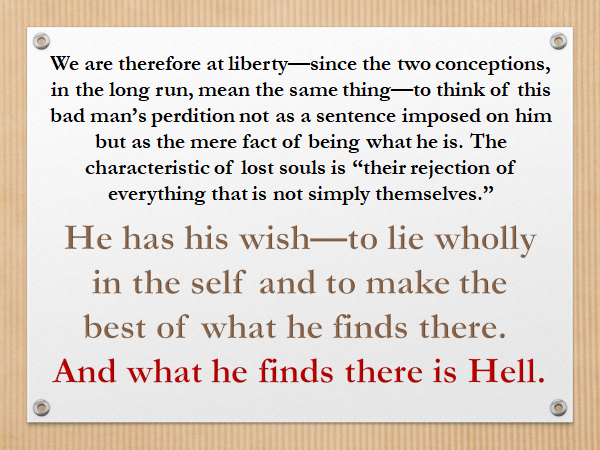

So Lewis understands this attitude of the unrepentant as he comments,

Lewis then shows the contrast between what occurs when a man enters into heaven as opposed to what transpires when he makes hell his eternal choice:

As the chapter comes to its conclusion, Lewis wraps up his argument about the appropriateness of hell by emphasizing what God has done to help steer people away from damnation:

Those final words have the stamp of finality upon them. As the damned obstinately refuse the pathway of grace, the Lord truly has no option but to allow them to go their own way. They want to be left alone. “Alas, I am afraid that is what He does.” But it is their choice.

Next week, we begin The Great Divorce, a book I first read more than forty years ago. It captured my imagination from the start and has continued to be one of my favorite Lewis books. The theme follows quite smoothly from what we discussed in The Problem of Pain as we examine the various reasons why denizens of hell continue to reject the appeals of heaven even when given a second chance.