I wrote in a earlier post that I’m preparing to teach C. S. Lewis’s entire Narnia series (in the published order) on Wednesday evenings at my church—the first three in the fall quarter and the last four in the winter (although here in Florida the word “winter” is more like “far less humid and much more comfortable”). My goal is to finish this preparation during the summer, as I will be quite busy when the new semester begins at my university.

What I appreciate the most is how this compels me to go into greater depth for each book, finding other sources that offer insight into what I might miss with just a cursory reading. I use PowerPoint extensively, as well as video for the books that have been turned into films, and I’ve exceeded one hundred PowerPoint slides now for each of the first four books.

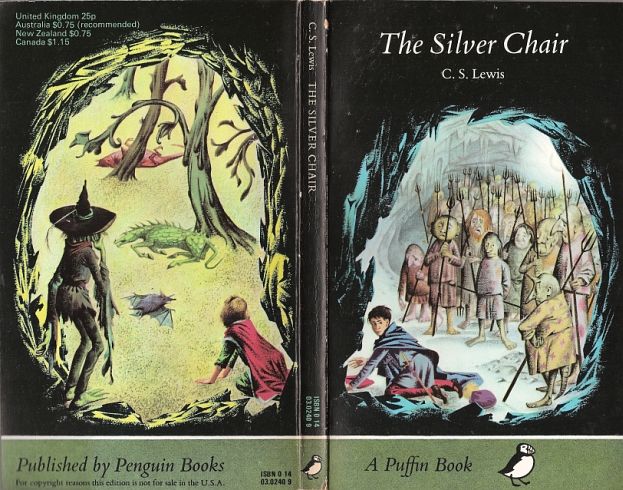

Just yesterday, I put the finishing touches on The Silver Chair. I had forgotten just how much wisdom Lewis packed into this one. Yes, the Narnia series is ostensibly written for children, but there is a depth within that most children will miss on a first reading. That’s why we adults keep coming back to this series—there’s always more to discover.

One of the most quoted passages is found early in the second chapter when Jill, newly transported to Aslan’s country on her way to Narnia, finds herself at a stream and very thirsty. Why doesn’t she immediately drink from the stream? Well, there’s this Lion close by. Naturally, she fears for her life. Will this Lion attack her? Then follows this interchange:

“Do you eat girls?” she said.

“I have swallowed up girls and boys, women and men, kings and emperors, cities and realms,” said the Lion.

“I suppose I must go and look for another stream.”

“There is no other stream,” said the Lion.

Children probably won’t catch the Biblical allusion, but I trust adults do as we contemplate Jesus’s words that He, and He only, gives the eternal water that will make us thirst no more.

Another widely quoted portion of the book comes later when the Queen of Underland smoothly and intoxicatingly attempts to deceive Jill, Eustace, and Puddleglum into believing that there is no world above, that Narnia doesn’t really exist. They almost succumb to her witchcraft until Puddleglum, one of his characters that Lewis most enjoyed creating, takes a stand against the witch’s deceptions:

It’s a moment of pure faith and courage, and it resonates with the reader: no matter what the world says, no matter what deceptions and false arguments are thrown our way, we must not depart from our confidence in the Lord and His character.

When they finally escape Underland and return to the real world of Narnia, there is a moment, captured by Lewis, that is rather sublime and comforting, and which puts the lie to the deception:

Yet it already felt to Jill and Eustace as if all their dangers in the dark and heat and general smotheriness of the earth must have been only a dream. Out here, in the cold, with the moon and the huge stars overhead (Narnian stars are nearer than stars in our world) and with kind, merry faces all round them, one couldn’t quite believe in Underland.

In the final chapter, Aslan returns in the full force of His personality and regal presence:

And when Eustace is confused about how Caspian can still be alive after he has died, Aslan responds, “Yes,” said the Lion in a very quiet voice, almost (Jill thought) as if he were laughing. “He has died. Most people have, you know. Even I have. There are very few who haven’t.”

“Even I have.” In the Narnian world, Aslan laid down His life for Edmund in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. In the world in which we live, Jesus Christ did the same, and not just for one, but for all.

I have no greater prayer than that these books, when I teach them, will draw each person in the class closer to the One for whom Lewis was writing.