One of the blessings I’ve received over the past few years is the opportunity to share with my church many of the key writings of C. S. Lewis. I began with The Screwtape Letters, then Mere Christianity, followed by a two-semester in-depth treatment of Narnia. In quick succession after that, I taught the Ransom Trilogy, a course on Lewis’s views on life, death, and eternity, followed by a selection of his best essays, and then a look at writers that Lewis admired: MacDonald, Chesterton, Tolkien, and Sayers. Currently, I am teaching a course on his excellent The Four Loves.

In the same way as Lewis’s WWII BBC broadcasts were transformed later into Mere Christianity, so The Four Loves began as radio broadcasts before he turned them into a full-fledged book. The broadcasts were recorded in London in 1958 and aired in the US on the Episcopal Series of the Protestant Hour radio program, now known as Day1. While the WWII broadcasts were mostly erased, and we have only snippets to hear from them, the series on the four loves is still available online. We get the full Lewis when we listen to them, a rarity to be sure.

In a letter to one of his correspondents in January 1958, Lewis outlined what he hoped to accomplish with the broadcasts.

The subject I want to say something about in the near future in some form or other is the four loves—Storge, Philia, Eros, and Agape. This seems to bring in nearly the whole of Christian ethics.

The book was published in 1960. Reviewers showered praise on this new Lewis offering.

That reviewer emphasized the quality of the writing. Anything by Lewis, he wrote, is a “treat.” Lewis writes with “utter courtesy and clearness.” His writing will “delight us” even if he were to write about such a dreary topic as economics. And I like his addendum: “nay, with golf.” For a review that focused more on the substance of the work, we have this:

That reviewer added:

The reviewer for the New York Times was fulsome with his praise:

Words like “classic,” “insight,” and “profound” stand out to me. Then there is this from Michael Novak that I love:

Novak calls The Four Loves a book that will bring “joy.” His use of the adjective “self-effacing” shows that he has grasped the nature of the man—his humility in what he writes. And calling Lewis’s writing one of the most “congenial pens in the language” is both insightful and amusing. How often would one call a pen congenial? Nowadays, it would be tantamount to referring to one’s laptop as “congenial,” wouldn’t it?

Novak also appreciates the range of Lewis’s mind, which indicates to me that he is quite familiar with the scope of Lewis’s works. The final sentence captures what Lewis truly is seeking to accomplish, helping readers come to the realization that the Christian life is a beautiful thing, not simply a list of rules and judgments. Lewis, he says, is “quietly sketching” that image. Novak himself reveals a congenial pen of his own in his description of what Lewis is achieving.

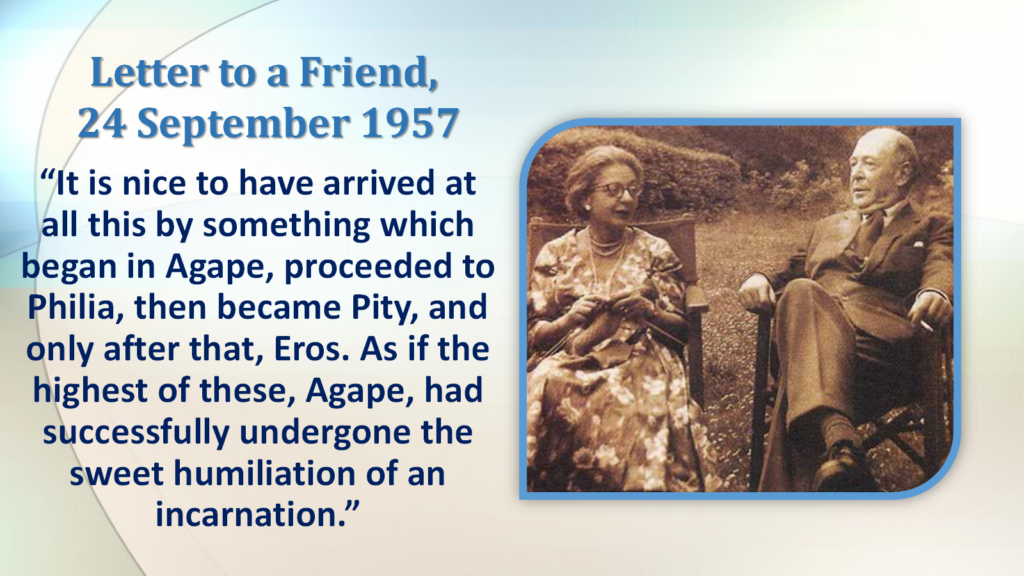

The year of the book’s publication, 1960, was a stressful time for Lewis. That was the same year that his wife, Joy, died. But the three-plus years of their marriage was a blessed time for him and helped, I think, provide an even greater depth of understanding of each of the four loves he writes about.

The year before he recorded the broadcasts, he reflected on what his marriage had brought to him and how it had shaped his knowledge of those four loves.

What we have in The Four Loves is the result of a lifetime of thinking and rethinking those concepts. We have the mature Lewis sharing his perceptions and/or perspectives. It is well worth the read—and well worth teaching it to a class in my church. I plan to continue this series on The Four Loves in this blog. As I teach it, I will share with you the fruit of that teaching.