We’ve had 47 presidencies in our history. Some were exceptional, others impactful one way or another, and a few almost entirely forgettable. The presidents after the Civil War up until Theodore Roosevelt, in the minds of probably most Americans, may fall into the “forgettable” category primarily because we truly have forgotten them. We focus on George Washington (as we should for the precedents he set) and Abraham Lincoln shouldering the burdens of a terrible civil war.

But some of those forgotten presidents deserve more recognition for their positive qualities—Grover Cleveland ranks high, in my opinion, as a president who held a high standard for constitutional fidelity and honesty. I won’t attempt in one short blog post to provide a comprehensive explanation for my opinion, but I will highlight some of those positives as evidence for why I hold that opinion.

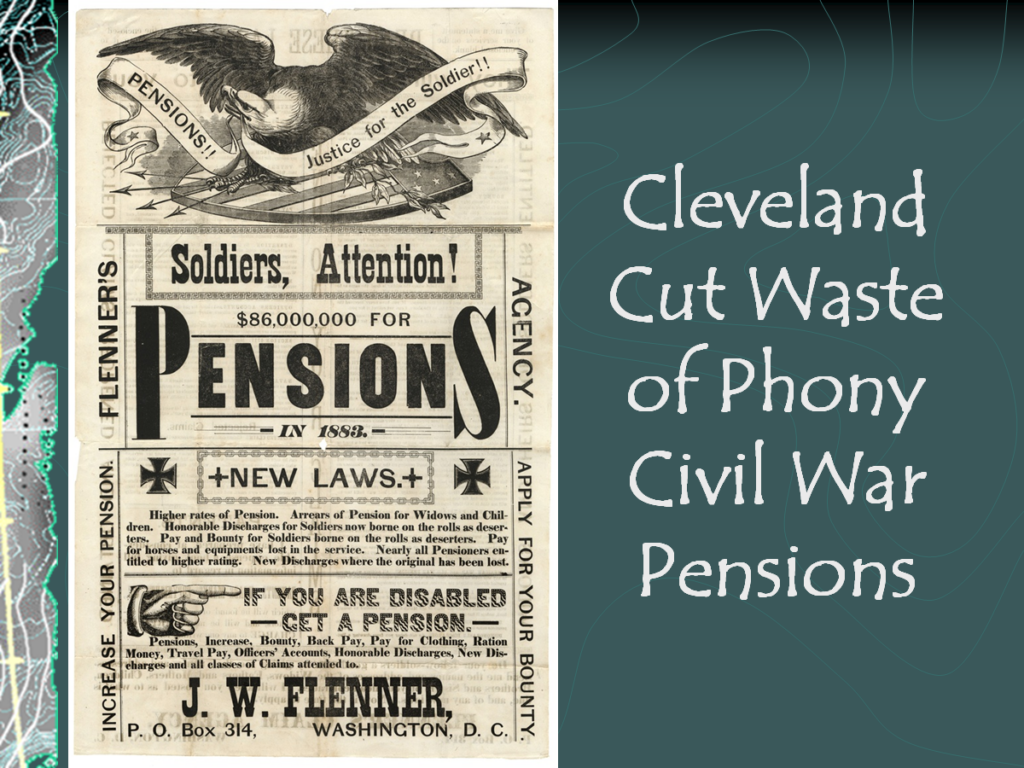

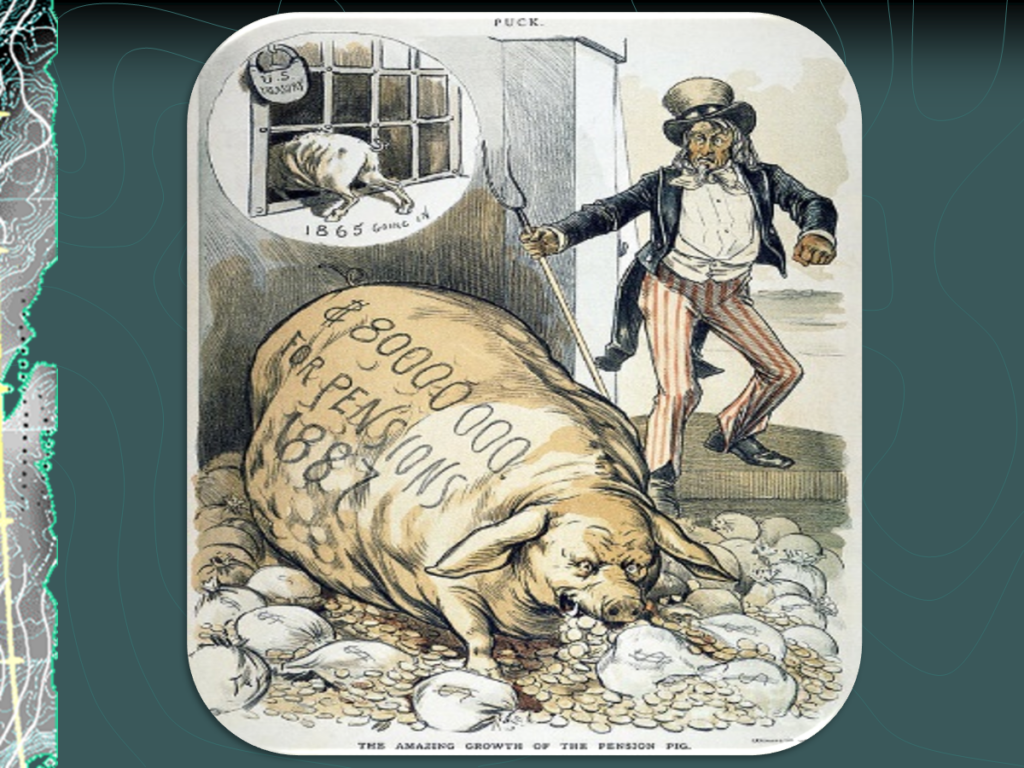

Cleveland was a Democrat, the first one in that party elected president after the Civil War. Upon taking office in 1885, he immediately set into operation a thorough examination of pensions being handed out to veterans from the war. At that time, Congress, controlled by Republicans, had been giving pensions to everyone who asked without really vetting the individuals. After all, what better way to solidify voters behind the party than to give them money? Cleveland decided instead to investigate each pension request and discovered many phony applications.

It’s a combination of sad and amusing to read some of the phony applications that flooded the Congress. One study of Cleveland’s vetoes of pensions notes the case of Cuthbert Stone. Congress had approved his pension for a supposed disability during his “long and faithful service.” But War Department records revealed that Stone enlisted in October 1861 and then was reported as a deserter from December 1861 until November 1864. When he was mustered out in January 1865, there was no record of a disability. Stone finally filed a claim in 1881, saying he had contracted a disability in 1863 “while he was being carried from place to place as a prisoner” due to his desertion. Congress, despite this abysmal record, awarded him a pension in recognition of his “long and faithful service and high character.”

Cleveland, in vetoing this bill for Stone, held that “the allowance of this claim would, in my opinion, be a travesty upon our whole scheme of pensions, and an insult to every decent veteran soldier.”

Then there was William Bishop, who hired himself out as a substitute in March 1865 and was mustered out a little over a month later, having spent half his army career hospitalized with measles. In vetoing Bishop’s pension bill, Cleveland wrote, with characteristic irony, “This is the military record of a man who remained in the army one month and seventeen days, having entered it as a substitute at a time when high bounties were paid. Fifteen years after this brilliant service and this terrific encounter with measles claimant discovered that his attack of the measles had some relation to his army enrollment, and that this disease had ‘settled in his eyes, also affecting his spinal column.’ This claim was rejected by the Pension Bureau, and I have no doubt of the correctness of its determination.”

This attention to false pensions underscores Cleveland’s overall philosophy of politics, as when he stated the following:

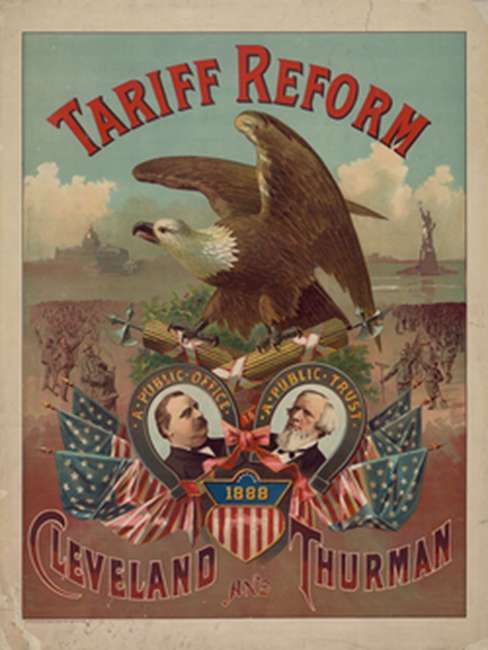

When Cleveland ran for reelection in 1888, one of his key policies was to cut back on tariffs and stand for free trade. He knew that the tariffs had two dismal effects: first, they would enrich only selected industries that didn’t want foreign competition; second, that the costs on foreign goods would only increase the cost of those goods for Americans who wanted to buy them.

His political advisors cautioned him about his stance, pointing to the probability that his views on tariffs would cost him New York, the most electoral rich state in the nation at that time. Cleveland, though, refused to back down on what he believed was right. True to his advisors’ fears, his trade policy was probably the reason he did lose New York and reelection. Yet what was Cleveland’s response?

In other words, principles should be our guide, even if it might cost us short-term gain. I honor Cleveland for his stand. Another interesting fact about this 1888 election is that he won the popular vote nationwide, but lost the electoral vote. He never complained about it because he understood the constitutional framework for a presidential election. Although he could have said the election was unfair, he simply accepted it and stepped down. Another reason for honor.

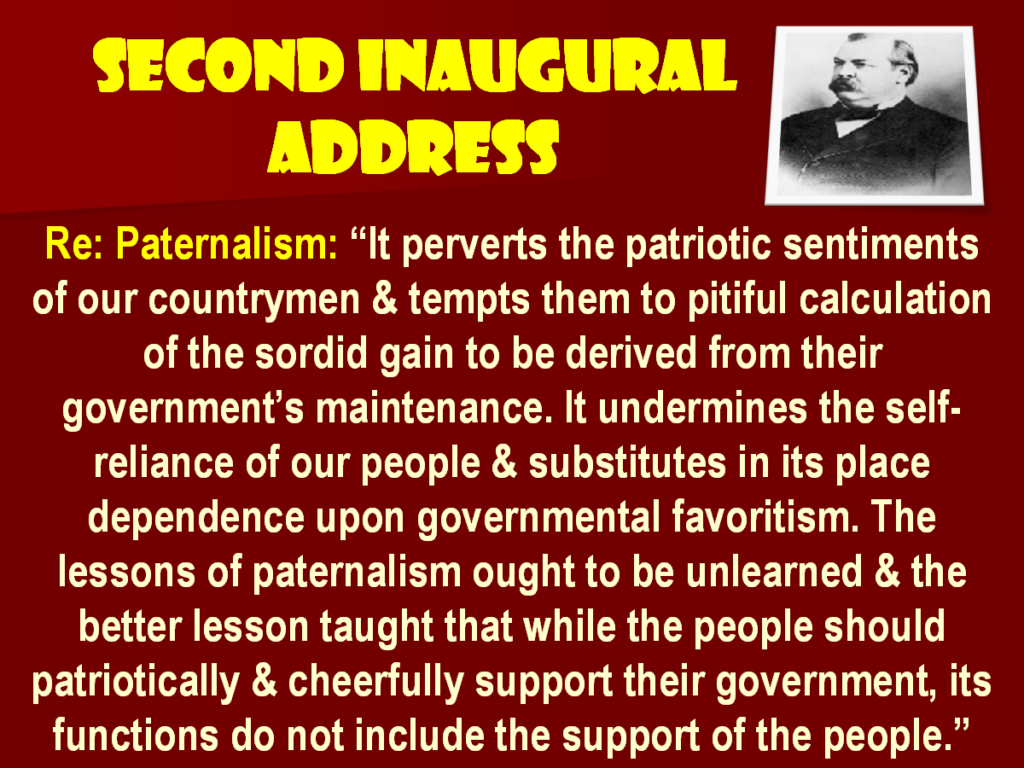

Cleveland ran again in 1892 and was reelected. His commitment to a government that stayed within its constitutional authority is reflected in his second inaugural address.

I have a couple of fine books that analyze the life and times of Grover Cleveland. The one you see here by H. Paul Jeffers is the most comprehensive. I highly recommend it.

My goal in writing about Cleveland is to encourage those who take the time to read this. In an age of cynicism about politics that has gone rampant for the past few decades, there is a need to highlight those in our past who had standards and who took the Constitution and the rule of law seriously.

Grover Cleveland is one of our “forgotten” presidents, but he shouldn’t be. So today, I honor him for his devotion to integrity in government.