How does one survey the vast number of essays C. S. Lewis wrote and pare them down to the twenty-or-so most essential ones? The problem arose for me as I prepared a course to teach at my church–slated for the January-April Parish Academy session. I earnestly desired to include his excellent thoughts in “Historicism,” but that essay is so prominent in my upcoming book (and the course I will develop based on that book), that I chose to exclude it for the essay course.

One’s subjectivism always will play a role in making the such choices. Which essays speak the most to me? Which ones will be easiest to explain and make application to the students’ personal lives? Ultimately, I decided to divide Lewis’s essays into three major categories: those dealing with the essential doctrines of Christian faith; those focused on education, since that was his career; and finally, essays that show the interaction of Christians with society.

I began with the area of Christian apologetics, which just happens to be the title of the first Lewis essay in my course.

Lewis begins by making it clear to this audience of youth leaders and younger clergy that they must understand their mission correctly. They are not to mix their own personal views with the essentials of the faith when they are explaining and defending it. “We are to defend Christianity itself—the faith preached by the Apostles, attested by the Martyrs, embodied in the Creeds, expounded upon by the Fathers,” he exhorts them. While we may hold opinions that we believe are consistent with the essentials, we must be careful to make this distinction: “When we mention our personal opinions, we must always make quite clear the difference between them and the Faith itself.”

He warns them that their upbringing, as well as the entire atmosphere of society, attempts to push us away from doctrinal truth toward modern trends.

Lewis’s next thought is one that I appreciate very much, and one I don’t hear often. He cautions against making the faith rest on science. Why? Because “science is in continual change.” The science of one hundred years ago is not the current science, and it will continue to change going forward.

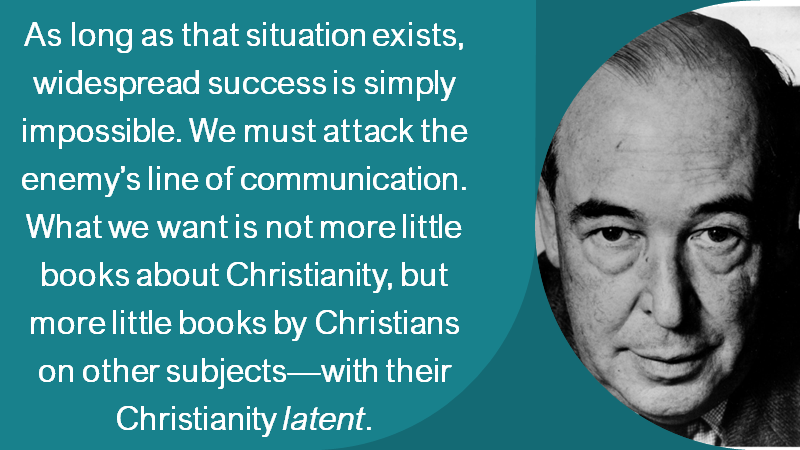

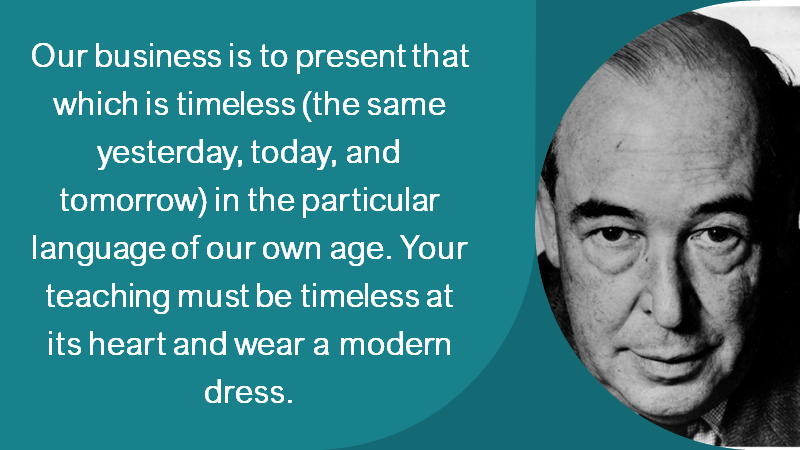

His apologetic then turns to a challenge: one can explain the Christian view to an audience—and perhaps capture their attention for half an hour or so—but then when they leave the church/auditorium/or whatever, they plunge back into a world that sees things differently. How does one deal with that? This is where he offers a solution that many Lewis readers may recall but are not sure where these words are found.

I know that’s a quote I’ve come across in many books about Lewis; it’s always nice to confirm such quotes, knowing their source. He continues,

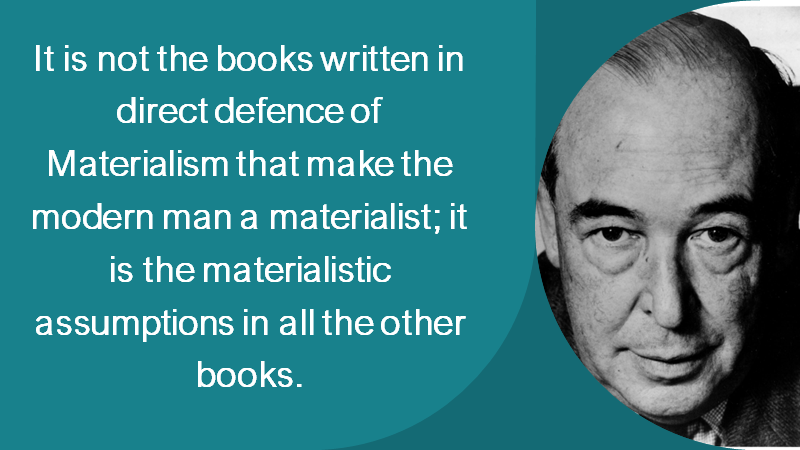

This is an argument in favor of Christians permeating society. I think it’s important to note that Lewis is not urging some kind of political upheaval or promoting a theocracy to “make” society Christian. He is instead encouraging his audience to take their faith into the popular culture and show how Christians can be the best thinkers and influencers for the good of society. This portion of the essay ends with a poignant thought:

The essay does not end there; there is much more of value to follow. I plan to delve further into it in my next post.