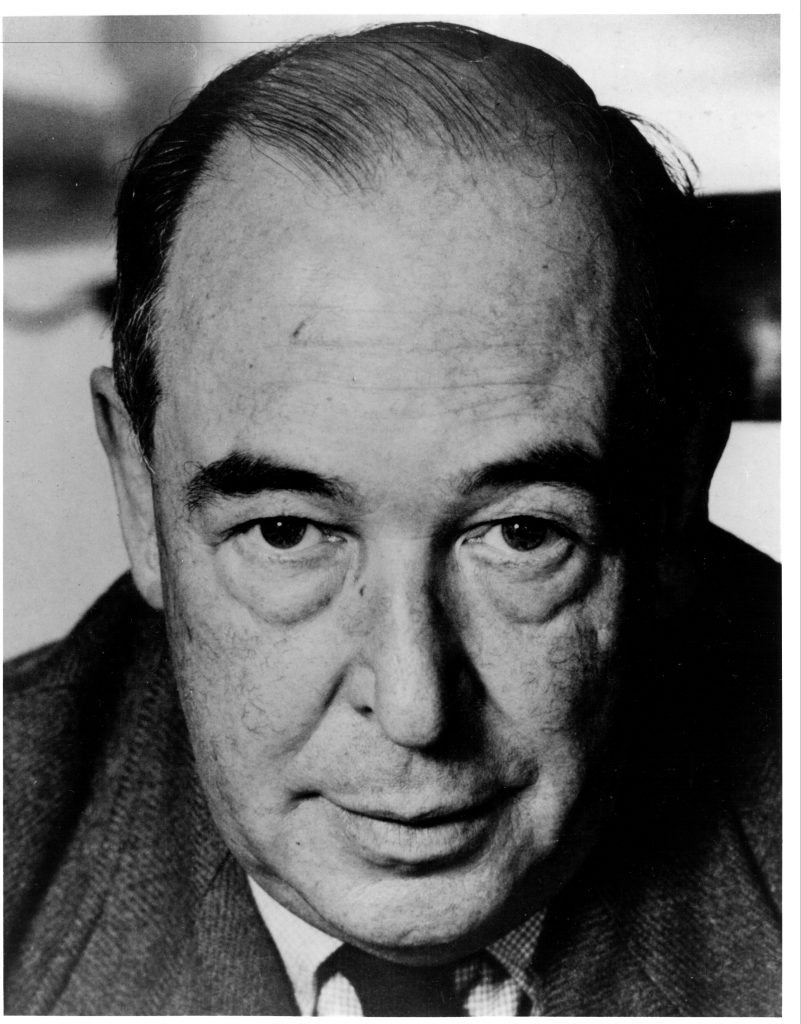

Recently, I was reminded of one of C. S. Lewis’s essays that I hadn’t thought about in quite a while; in fact, I couldn’t recall if I had read it. Yet, as a professor of history, I must have perused his “Is History Bunk?” at some time or other. So I checked into it as if it were a new piece of Lewis’s corpus that I hadn’t seen before.

The essay is found in the collection called Present Concerns, the repository of three of my favorite Lewis essays: “Equality,” “Democratic Education,” and “Modern Man and His Categories of Thought.” Why, I wondered, would I be so attracted to those essays and not remember “Is History Bunk?”

So I decided to give it a fresh look, and I’m glad I did.

It’s an easy read, consisting of only four pages. Lewis’s first contention is one that hit home: the usual reasons for studying history. “History is defended as instructive or exemplary: either ethically (the lasting fame or infamy which historians confer upon the dead will teach us to mind our morals) or politically (by seeing how national disasters were brought on in the past we may learn how to avoid them in the future).”

I admit to using these rationales as I teach students. After all, history seems to need defending nowadays. Students wonder how a history degree will get them a job; we do our best to enlighten them that depth of knowledge, the ability to research, the value of analysis, and training in excellent writing will make them valuable to employers in many fields. And I believe all of that. Lewis himself, in the essay, makes a case for literary history as one example of value. Yet he does so not merely on the basis of practicality for finding a job, but as “seeking knowledge of the past … for its own sake,” thereby “gratifying a ‘liberal’ curiosity.”

Knowledge for its own sake, Lewis says, descends from Aristotle, but the idea of accumulating knowledge for that reason runs counter to our modern sensibilities.

This conception … has always been baffling and repellent to certain minds. There will always be people who think that any more astronomy than a ship’s officer needs for navigation is a waste of time. There will always be those who, on discovering that history cannot really be turned to much practical account, will pronounce history to be Bunk. Aristotle would have called this servile or banausic [i.e., mundane]; we, more civilly, may christen it Fordism.

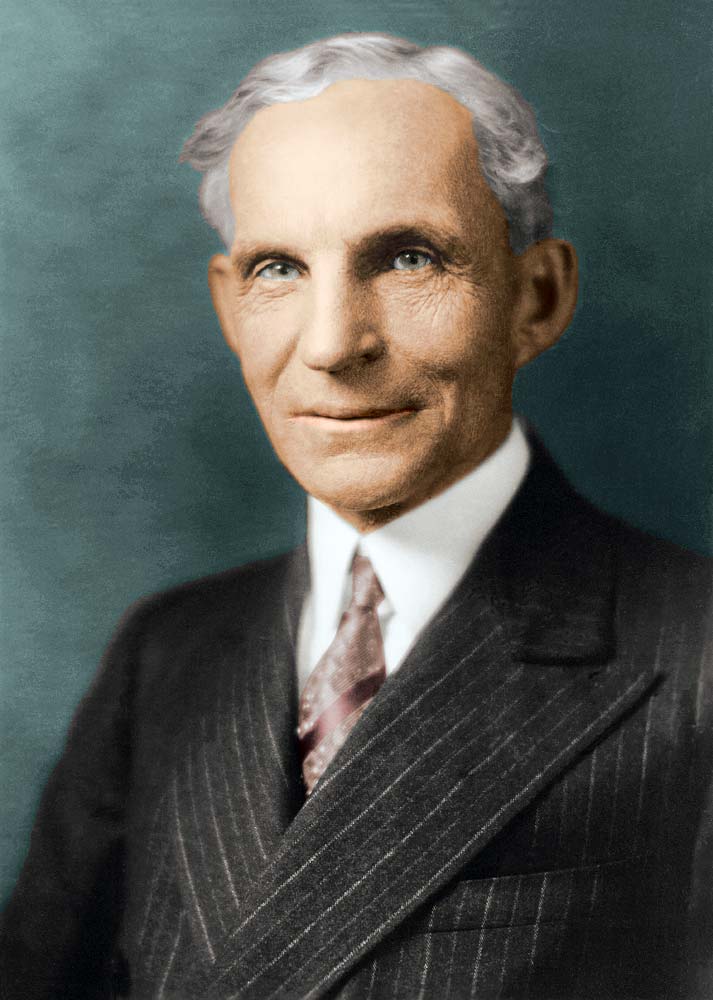

At first, I was puzzled by “Fordism.” Was this some obscure philosophy of Lewis’s age of which I was unaware? Fortunately, I came to my historical senses and recalled the famous/infamous quote from American automaker Henry Ford.

In interviews with newspapers in 1916, Ford did say, in effect, that history is bunk. The interviewer with the New York Times related, “When in our ‘discussion’ of a nation’s need for defensive strength history was appealed to, Mr. Ford replied that he did not believe in history, that history was of the past and had no bearing upon the present and that, there being nothing to be learned from it, history need not be studied nor considered.”

Ten days later, when interviewed by a reporter at the Chicago Tribune, Ford asserted, “History is more or less bunk. It is tradition. We don’t want tradition. We want to live in the present and the only history that is worth a tinker’s dam is the history we make today.” He concluded his remarks with these words: “That’s the trouble with the world. We’re living in books and history and tradition. We want to get away from that and take care of today. We’ve done too much looking back. What we want to do and do it quick is to make just history right now.”

Ford’s views are the essence of a man who can’t see much value in the study of a subject for the sake of learning in itself. Everything, for those of his mindset, must have practical application. Now, there’s nothing wrong with practical application. That’s what I try to convince students of when they question whether a history degree has practicality. But modern society is immersed in the belief that the most important thing when it comes to education is whether one “gets a job.”

I’m convinced that a thorough liberal arts education should be the basis for any specialized field a person chooses to enter. Knowledge for the joy of satisfying curiosity helps create even more curiosity. And the more one knows, the more one can see the true values that a society needs, which, to my way of thinking, is quite practical.

As I said, Lewis wrote this essay in the context of literary history, but his analysis applies to all types of history. History studies mankind. We learn what men did and, if we look closely enough, why they did what they did. If this is not “practical” enough for some people, that’s understandable, coming from their worldview.

Yet that kind of knowledge is significant. Even if it doesn’t reach the Fordism standard, does that mean we shouldn’t learn for the sake of learning? I like how Lewis concludes the essay.

For if one values literary history as history [rather than as literary criticism], it is of course very clear why we study bad work as well as good. To the literary historian a bad, though once popular, poem is a challenge; just as some apparently irrational institution is a challenge to the political historian. We want to know how such stuff came to be written and why it was applauded; we want to understand the whole ethos which made it attractive. We are, you see, interested in men. We do not demand that everyone should share our interests. …

We cannot, pending a real discussion, let pass the assumption that this species of history, any more than others, is to be condemned unless it can deliver some sort of “goods” for present use.

Although I hope and expect that my reading and teaching of history will accomplish some level of ethical/spiritual enlightenment and will help guide our generation into wise decisions, both in the private sphere and in the public, I read and learn because I delight in learning. God has made me this way, and I want to fulfill His purposes in my life.