One of the aspects of C. S. Lewis’s writings that I’ve come to see more clearly is that he repeats key concepts regardless of the genre, whether via autobiography, apologetics, or fiction. As I’ve been re-reading the Ransom Trilogy, I’m seeing this better than ever. Let me offer one example that shows up in both Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra.

As Elwin Ransom tries to understand hrossa society on Malacandra, he questions his friend Hyoi about pleasures. In the context of population growth and providing enough food for everyone, Ransom is puzzled by the hrossa‘s willingness to stop sexual relations after having a certain number of children. He asks Hyoi whether the begetting of children is not a pleasure for his species. “A very great one, Hman. This is what we call love,” is the response.

But Ransom, from the particular species called “human,” can’t seem to grasp the logic. He informs Hyoi that “if a thing is a pleasure, a hman wants it again. He might want the pleasure more often than the number of young that could be fed.” Hyoi has to ponder that and then asks, “You mean that he might do it not only in one or two years of his life but again? . . . But why? Would he want his dinner all day or want to sleep after he had slept? I do not understand.”

Ransom doesn’t let this go, as he objects, “But a dinner comes every day. This love, you say, comes only once while the hross lives?” But Hyoi has a different perspective, as he explains, “But it takes his whole life. When he is young he has to look for his mate; and then he has to court her; then he begets young; then he rears them; then he remembers all this, and boils it inside him and makes it into poems and wisdom.”

Even though the hrossa are fictional and God doesn’t expect human marriages to be the same, nevertheless Lewis is stressing a significant point here. Hyoi continues:

A pleasure is full grown only when it is remembered. You are speaking, Hman, as if the pleasure were one thing and the memory another. It is all one thing. … What you call remembering is the last part of the pleasure. … When you and I met, the meeting was over very shortly, it was nothing. Now it is growing something as we remember it. But still we know very little about it. What it will be when I remember it as I lie down to die, what it makes me all my days till then—that is the real meaning. The other is only the beginning of it.

What Lewis is doing is pointing out how we focus so much on the immediate pleasure of an experience at the expense of seeing the bigger picture: each experience adds to the total life of each individual. We should grow in our understanding of the meaning of our experiences rather than just live for an experience in the moment. Then, at the end of our life, we should look back and appreciate how every pleasure and good thing has contributed to an entire life.

Having that perspective lifts us out of the tyranny of the moment and erases the tendency to want to relive those good moments, as though our life isn’t continuing with new experiences to add to the ones that have already passed. Hyoi concludes with this thought:

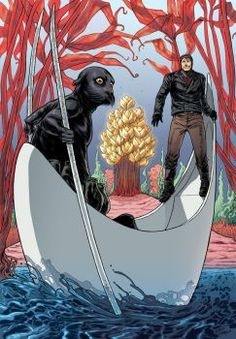

This “pleasure principle” shows up again when Ransom arrives on Perelandra. His first plunge (literally) into the seas of the planet fills him with a deep pleasure that he can barely contain. The entire atmosphere seems to exude pleasure.

When he finally crawls onto one of Perelandra’s floating islands, all of his senses are alive. “The smells in the forest were beyond all that he had ever conceived. To say that they made him feel hungry and thirsty would be misleading; almost, they created a new kind of hunger and thirst, a longing that seemed to flow over from the body into the soul and which was a heaven to feel.” Ransom, like anyone in a new and alien environment, would naturally experience some fear, yet “if he had any fear now, it was a faint apprehension that his reason might be in danger. There was something in Perelandra that might overload a human brain.”

Then he sees trees with great globes of a yellow fruit hanging from them. Are they safe to eat? He takes the chance and has a gastronomic experience unlike any other. He began to simply sip the juice cautiously, “but the first taste put his caution all to flight.” Like everything else in this world, the pleasure was overwhelming.

“It was, of course, a taste, just as his thirst and hunger had been thirst and hunger. But then it was so different from every other taste that it seemed mere pedantry to call it a taste at all.” Expectations were not just met; they were exceeded.

It was like the discovery of a totally new genus of pleasures, something unheard of among men, out of all reckoning, beyond all covenant. For one draught of this on earth wars would be fought and nations betrayed. It could not be classified. He could never tell us, when he came back to the world of men, whether it was sharp or sweet, savoury or voluptuous, creamy or piercing. “Not like that” was all he could ever say to such inquiries.

Ransom considered eating a second one, but he suddenly realized that his hunger and thirst had gone. How could he not experience this pleasure again—right now? Everything in his past urged him to do so; this is what humans do when they find such a pleasure. Yet he held back. Lewis explains,

It is difficult to suppose that this opposition came from desire, for what desire would turn from so much deliciousness? But for whatever reason, it appeared to him better not to taste again. Perhaps the experience had been so complete that repetition would be a vulgarity—like asking to hear the same symphony twice in a day.

Lewis is making the same point here that he did in the previous book. There is a right time for certain pleasures, and to become greedy and try to grasp the full pleasure once again immediately would be, as he put it, “a vulgarity.” It wouldn’t be the same as the initial pleasure. And just the growing remembrance of the pleasure—whether sexual relations as understood on Malacandra or this perfect explosion of taste Ransom discovered on Perelandra—would become part of one’s entire life. We are not to be mastered by anything; all things are to be carried out in God’s way.

I think we can make a connection as well to Lewis’s autobiography, Surprised by Joy, in which he tells of his relentless pursuit to recapture moments of joy, only to realize how elusive that first experience is to repeat. He had to finally realize, as he did after conversion, that the joy he was seeking could only be found in one place, in one Person. I like the way he ends that book.

I now know that the experience [joy], considered as a state of my own mind, had never had the kind of importance I once gave it. It was valuable only as a pointer to something other and outer. While that other was in doubt, the pointer naturally loomed large in my thoughts.

When we are lost in the woods the sight of a signpost is a great matter. He who first sees it cries, “Look!” The whole party gathers round and stares. But when we have found the road and are passing signposts every few miles, we shall not stop and stare. They will encourage us and we shall be grateful to the authority that set them up. But we shall not stop and stare, or not much; not on this road, though their pillars are of silver and their lettering of gold. “We would be at Jerusalem.”

All the pleasures of this life come from the hand of God. But they are merely signposts pointing to Him. When we make those pleasures the goal in life, we are really lost in the woods. When we see them for what they are intended to be, we are grateful for them as we walk the path that the Lord has laid out for us.