In my new position as a salaried teacher at my church, I’ve been able to do what I love best: develop courses and then offer them to a group of Christians who are characterized by an eagerness to learn more. I recently completed “C. S. Lewis on Life, Death, and Eternity” and am now addressing a class of more than 50 each week on the topic of Early Church History.

Throughout my adult life, I’ve always had a deep interest in this time period, as the church began and found its way into the world, eventually eclipsing the old religions of the Roman Empire. It’s a fascinating story, filled with drama, intrigue, hardship, and victories. Last week, I embarked on an explanation of the issue of heresies in the early church and how they were handled. The life of Christ through the Holy Spirit infused this early church, but it did need to come to grips with a settled theology: it needed to figure out what was essential to believe and what had to be avoided in order to carry forth the mission Christ gave to create disciples. Theology—an explanation of what we believe and why—came to the forefront.

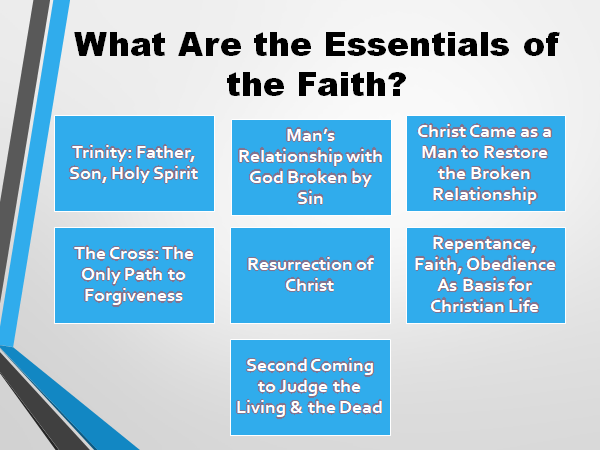

What are the essentials of this theology? With what should we be concerned as committed Christians? I did my best to come up with a list of what I consider the essentials.

While there are a number of attempts to explain how the Trinity functions, it is nevertheless clear that there is a Father, a Son, and a Spirit. The nature of the Godhead is a fundamental starting point in understanding the faith. The problem of sin and the solution through Christ’s suffering on the Cross cannot be removed from the faith without destroying the faith. Again, there are different theological opinions on how the atonement works, but the fact that it is the only way to take care of the sin that separates man from God is not in question for Christian orthodoxy.

As the apostle Paul stated, if Christ was not raised bodily from the dead, our faith is futile and we are of all people the most to be pitied. Only through repentance, faith, and obedience is the Christian life a reality, and we await the Second Coming and the final judgment. These are all essentials.

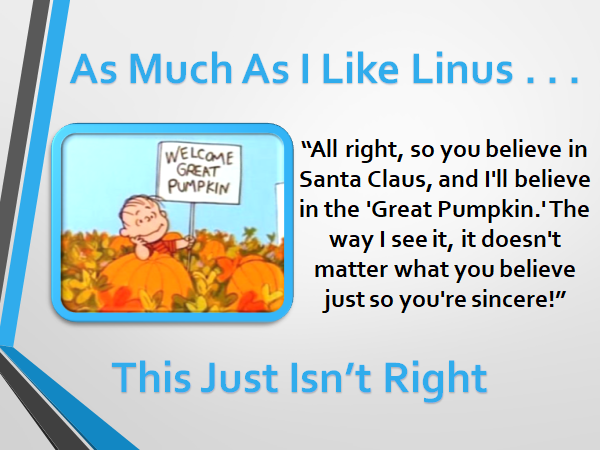

Just being sincere about what one believes is not enough; one can be sincerely wrong.

All of which leads to the matter of what constitutes heresy. Here’s the definition I presented to the class.

Notice that last part highlighted in yellow. I believe it is necessary to make a clear distinction between a genuine heresy and simply a difference of opinion on matters that are not part of the essentials. I’ve already remarked that even with those essentials, people can have varying explanations for how they should be understood. What, then, of other issues like baptism, communion, or, in America, even the drinking of alcohol? If I don’t think baptism is right without immersion, are you a heretic for not immersing? Conversely, as we saw in the Reformation, when the Anabaptists concluded that immersion was the only legitimate way to baptize, both the Catholics and other Protestant reformers disagreed so strongly with them that they even executed them as heretics.

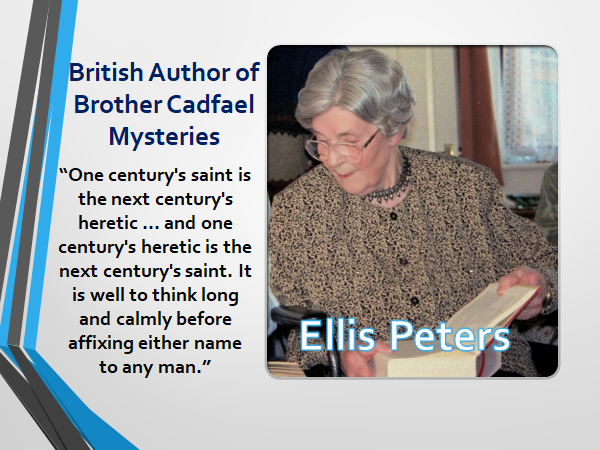

This is where the church through the ages has gone very wrong, failing to make the distinction between heresy and different interpretations of Scripture. I found this quote that I thought was to the point:

This introduction to heresy was foundational going forward. After presenting what you see here, I did go into a discussion of the Gnostic heresy that plagued the early church. What I hope is that this helped my class see the difference more clearly—a heresy rejects an essential of the faith; a difference of opinion on disputable matters does not.

As Paul admonished the Roman Christians in chapter 14 of his letter, “Accept him whose faith is weak, without passing judgment on disputable matters. . . . Who are you to judge someone else’s servant? To his own master he stands or falls. And he will stand, for the Lord is able to make him stand.”

May we be firm in the essentials of the faith, but may we also give latitude in the non-essentials.