I first read The Great Divorce when I was an undergraduate at Purdue University a long time ago. To be honest, that reading occurred less than a decade after C. S. Lewis’s death. I’ve reread it more times than I can recall and have offered it to students in my university course on Lewis.

In that course, though, there are so many Lewis books to read that I cannot give it the time it deserves for discussion. But I’ve been able to rectify that rushed approach in the current class I’m teaching at my church, one that I’ve titled “C. S. Lewis on Life, Death, and Eternity.” Over two weeks, we’ve spent three hours delving into what I consider one of Lewis’s most imaginative works.

For those unfamiliar with Lewis’s approach, the summary is this: What would it be like if the denizens of hell could take a trip to the outskirts of heaven to be given one last chance to repent of their sins and receive God’s mercy? Would anyone take the offer? If not, what would keep them from bending the knee, acknowledging their sins, and receiving forgiveness, thereby entering into eternal life?

In the preface, Lewis makes clear that this is not a book setting forth some kind of special revelation about the nature of either hell or heaven; he writes it simply as a supposal—what if there would be a second chance—how might it play out? The “supposal” perspective is how he describes the Narnia tales—what if Christ were to appear in a different form in a different world? The approach in The Great Divorce is similar.

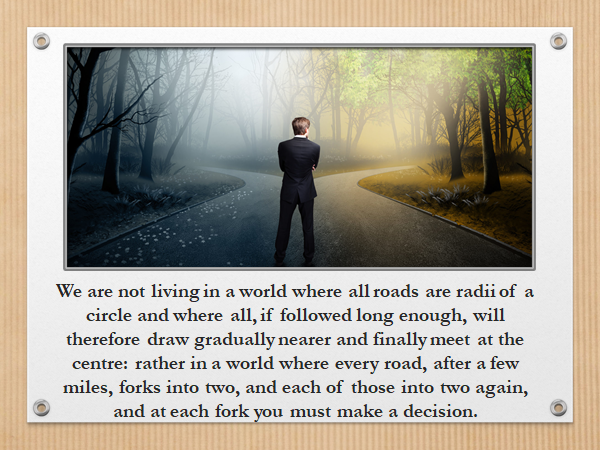

The preface also clearly lays out the worldview behind the fantasy:

In other words, our decisions in life are momentous. And those decisions come at us constantly.

When the damned arrive in heaven, they discover that in that “solid” place, they are little more than ghosts. Each one is met by someone they knew on earth who has come a long way just to talk with them and try to convince them to abandon their depravities. The book is filled with accounts of these interventions.

Lewis depicts the many types of sins that keep us from a relationship with the Lord. Some are heinous sins in the reader’s eyes, while others may seem more respectable. Yet he peels away the outer layers of respectability—love for one’s child, love for one’s art or talent—and reveals the pride or possessiveness at the root of each.

One of the encounters that initially grabbed my attention from my very first reading of the book was with the individual Lewis calls “The Episcopal Ghost.” So taken was I with this encounter that I used it as the basis for my final project in a class on television production. My first degree, years before I turned to history, was in radio, television, and film production, a field I worked in for a few years.

The Episcopal Ghost is met by a fellow religionist who had turned “narrow” in his later years, meaning he had come to the true Christian faith. The heavenly agent attempts to shed light on the ghost’s actual predicament, as he doesn’t seem to understand his fate:

Satan has blinded the minds of the unbelieving, and some of the most blind are those who think they have the truth.

As the Lewis character in the book ponders what he is seeing, Lewis the author introduces George MacDonald, the Christian writer who had baptized his imagination as a young student. MacDonald then becomes the guide to what is happening in these encounters.

MacDonald brings spiritual enlightenment to the Lewis character as he explains the choice each ghost must make. Probably the most-quoted portion of The Great Divorce is this bit of insight from MacDonald:

Hell was created for the devil and the other fallen angels. Man was never meant to go there. Yet the way is wide that leads to hell while the way is narrow to heaven—and few are they who follow that narrow path. This is dismal news, but what comes immediately after this quote is the promise Christ gives to all:

The Great Divorce illuminates that open door. It aids in understanding the varied deceptions of sin, the need for repentance, and the boundless mercy that one of the citizens of heaven refers to as the Bleeding Charity. When we accept the Bleeding Charity of the Cross, the gates of heaven open wide.