“If only life would get back to normal!” Have you ever said that during times of exceptional distress? If you are human, you undoubtedly have expressed that, or something similar, at times.

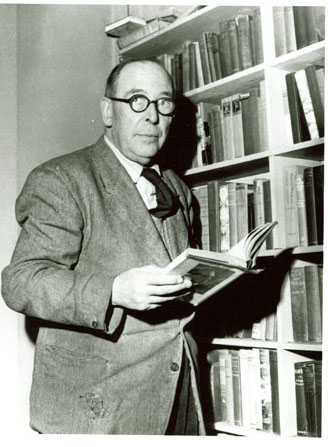

C. S. Lewis, in an essay called “Learning in War-Time,” found in the series of essays collected under the title of The Weight of Glory, helps us to reorient our thinking on this subject. He wrote that essay, obviously, during WWII. If ever anyone might long for a return to the normal, it would be a person caught in the middle of a war that seemed to engulf most of the civilized world. Yet Lewis throws the cold water of reality on those with that longing:

The war creates no absolutely new situation; it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it. Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. . . . We are mistaken when we compare war with “normal life.” Life has never been normal. [emphasis mine]

The duties of everyday life, Lewis contends, must go on even in those times when the temptation is to set them aside because one must give 100% of one’s thoughts and actions to something as all-encompassing as a war. But, Lewis reasons, even our faith, which “must occupy the whole of life,” doesn’t require the cessation of all other activities.

Lewis affirms that “there is no question of a compromise between the claims of God and the claims of culture, or politics, or anything else.” That’s a relevant warning for so many of us today who may put politics or anything else in the place of our obligation to be Christ’s image-bearers. We have a tendency to place politics, especially, almost on a plane with God’s Kingdom, but “God’s claim is infinite and inexorable.” Nothing competes with his Lordship. Yet, Lewis continues, “in spite of this it is clear that Christianity does not exclude any of the ordinary human activities. St. Paul tells people to get on with their jobs.”

The main reason behind Lewis putting these thoughts together in this essay is that some were criticizing universities like Oxford for maintaining their daily academic calendar during the war. So, in one sense, Lewis was offering an apologetic for his own profession. No war—even one with the likes of a Hitler—should consume our entire lives. Learning must go on. “Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason, because bad philosophy needs to be answered.” It was Hitler’s “bad philosophy,” of course, that was responsible for the war in the first place.

Lewis then gladdens the heart of a historian (that would be me) when he gets to the crux of his argument:

Most of all, perhaps, we need intimate knowledge of the past. Not that the past has any magic about it, but because we cannot study the future, and yet need something to set against the present, to remind us that the basic assumptions have been quite different in different periods and that much which seems certain to the uneducated is merely temporary fashion.

A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village; the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.

Have you noticed any “great cataract of nonsense” flowing from the press and social media of our day? If not, you may not be paying attention. Lewis’s goal is to help us focus on what really matters, what really is true. He helps us contemplate the temporariness of this life and the eternity that awaits.

“There is no question of death or life for any of us,” Lewis reminds us, “only a question of this death or of that—of a machine gun bullet now or a cancer forty years later. What does war do to death?” He answers: “It certainly does not make it more frequent; 100 percent of us die, and the percentage cannot be increased.”

We are treated daily, if we pay attention, to glorious visions of the future once we erase all of man’s [take your pick] greed, lack of humanity toward others, income inequality, healthcare issues, etc, etc. We sometimes believe government can answer all of our problems. It’s particularly galling to me when those who call themselves Christians seem to replace the provision of God with the provision of government. Lewis, though, once again comes through with that bracing, cold water of reality:

If we thought we were building up a heaven on earth, if we looked for something that would turn the present world from a place of pilgrimage into a permanent city satisfying the soul of man, we are disillusioned, and not a moment too soon.

Go ahead. Be disillusioned. We need to set aside phony visions and remember that life is a pilgrimage. This world is not our permanent home.