Historians must always be careful not to accept too readily what may appear to be fantastical accounts. We are trained to check sources for confirmation of stories that may be more legend than actual history.

Yet sometimes those legends come about because they are based on real events. Such, perhaps, is the legend of St. Brendan. Here’s the story, received today in an e-mail from the Christian History Institute. See what you think about the accuracy of what we consider a legend nowadays.

ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR BOOKS of the Middle Ages recounted the travels of an Irish monk, St. Brendan. Brendan was a missionary who planted monasteries in northwest Europe. Many places are named after him and when he died at ninety-three, he was buried at the town of Clonfert in County Galway. However, we remember him today as possibly the first European to reach America.

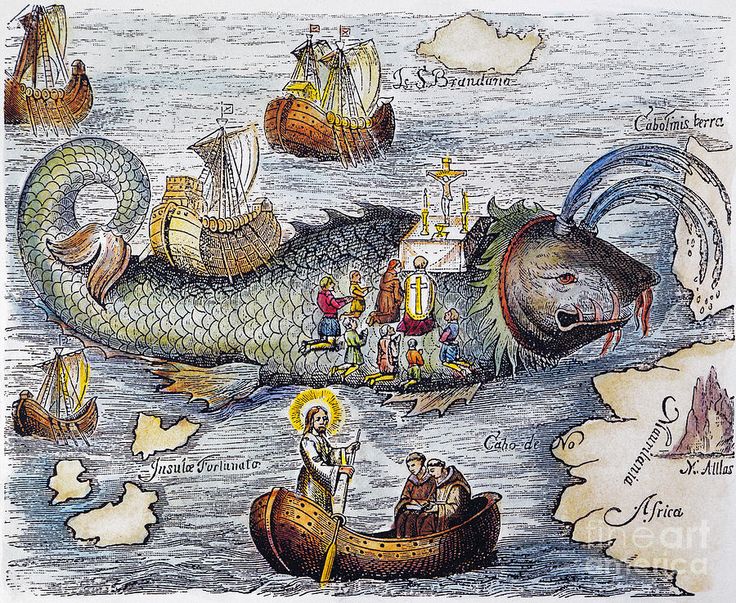

Some of the details of the Brendan legend became incredible over the years—crystals floating in water, islanders bombarding the monk and his crew with flaming rocks, a whale mistaken for an island. Brendan is said to have offered communion each Easter while he was at sea on the back of a friendly whale. On a wet rock, he supposedly found a remorseful Judas chained and suffering. Demons carried off one of his sailors. He and his companions observed sheep as big as stags. Fallen angels in the guise of birds appeared to them. All these cheerful inventions caused scholars to dismiss the whole account as fantasy. Nonetheless, Christopher Columbus—who believed that Brendan followed a southern route—invoked the story to inspire his captains and crews.

Twentieth century historian Tim Severin studied nautical maps and became convinced a northern route fit Brendan’s description better. He and a handful of companions built a hide-covered curragh (a small, round boat with a wickerwork frame) such as Brendan would have sailed, christened it Brendan, and set sail in 1976 to learn whether an Irish craft could have made a voyage to the new world.

Proceeding from Brandon Creek, Ireland, the historian and his small team sailed northward to the Hebrides Islands and on to the Faroes (Brendan’s “Island of Sheep”) from which one can see Brendan’s “Paradise of Birds,” named for the many which nest in the neighborhood. The next stop was Iceland. Along the entire journey, whales sported alongside, even swimming under the curragh as if to vindicate Brendan’s tale.

The curragh weathered frightful storms, leaking very little. Because of bad weather, the Brendan had to winter in Iceland inside an airplane hanger. The volcanic island was quiet at the time, but has been known to fling flaming sulfur and rock into the sky, another indication that parts of the legend had a basis in reality.

is a fascinating look at other prominent Celtic Christians who shaped the world.

In 1977, the five men resumed their voyage. Now they saw icebergs riding like shiny crystals in the sea and eventually entered a fog such as Brendan’s tale described. Soon afterward, they found themselves in pack ice. The curragh proved ideal for creeping through the pack, its hide-covered frame able to flex where the ice would have crushed a wooden or steel hull. About two hundred miles from Newfoundland, ice punctured the skin of the boat. Fortunately the hole was near enough to the surface that the crew could repair it.

On the evening of this day, 26 June 1977 Brendan made landfall in Newfoundland. “And the legend had looked more like the truth with every mile,” as Tim Severin noted. His replication of Brendan’s voyage did not prove it happened, but it did show that fifth-century Irish technology was capable of making the dangerous voyage and reminded us that those Irish monks were men of strength and courage.

I’ve always been fascinated by the Irish monks in the early centuries of Christianity. A book I read many years ago still stays with me: How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe. That story, which is historically accurate, rests on the shoulders of many of those faithful Christians of that early era.

How much of the St. Brendan legend is true? Well, I’ll discount finding Judas on the voyage, but much of the rest does seem to rest on fact, albeit explained in a more fantastical way.