The Templeton Prize, established in 1972 by philanthropist Sir John Templeton, is awarded each year to a person “who has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension, whether through insight, discovery, or practical works.” The monetary award for this prize is continually revised upward to ensure it exceeds the award given to Nobel winners. Why? It is “to underscore Templeton’s belief that benefits from discoveries that illuminate spiritual questions can be quantifiably more vast than those from other worthy human endeavors.”

I like that.

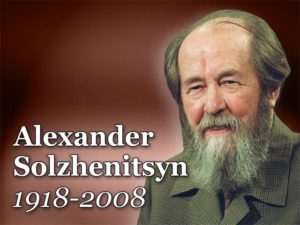

The Templeton Prize, back in 1983, was awarded to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. I like that, too. Yesterday, I highlighted Solzhenitsyn’s challenging Harvard commencement address in 1978, an address that pointedly accused the West of abandoning its spiritual heritage.

The Templeton Prize, back in 1983, was awarded to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. I like that, too. Yesterday, I highlighted Solzhenitsyn’s challenging Harvard commencement address in 1978, an address that pointedly accused the West of abandoning its spiritual heritage.

His Templeton Address, entitled “Men Have Forgotten God,” builds on his comments at Harvard. The first three paragraphs set the tone for this sobering look at the demise of our Christian heritage:

More than half a century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of older people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

Since then I have spent well-nigh fifty years working on the history of our Revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous Revolution that swallowed up some sixty million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

What is more, the events of the Russian Revolution can only be understood now, at the end of the century, against the background of what has since occurred in the rest of the world. What emerges here is a process of universal significance. And if I were called upon to identify briefly the principal trait of the entire twentieth century, here too, I would be unable to find anything more precise and pithy than to repeat once again: Men have forgotten God.

Solzhenitsyn lived under the Communist regime in the USSR; he was persecuted by it and understood its underpinnings:

Within the philosophical system of Marx and Lenin, and at the heart of their psychology, hatred of God is the principal driving force, more fundamental than all their political and economic pretensions. Militant atheism is not merely incidental or marginal to Communist policy; it is not a side effect, but the central pivot.

But this address is not merely a jeremiad, lamenting the sad state of affairs. Solzhenitsyn reveals that beneath all the persecution, all the hatred of Christianity, the Communist state could not wipe it out.

But this address is not merely a jeremiad, lamenting the sad state of affairs. Solzhenitsyn reveals that beneath all the persecution, all the hatred of Christianity, the Communist state could not wipe it out.

But there is something they did not expect: that in a land where churches have been leveled, where a triumphant atheism has rampaged uncontrolled for two-thirds of a century, where the clergy is utterly humiliated and deprived of all independence, where what remains of the Church as an institution is tolerated only for the sake of propaganda directed at the West, where even today people are sent to the labor camps for their faith, and where, within the camps themselves, those who gather to pray at Easter are clapped in punishment cells—they could not suppose that beneath this Communist steamroller the Christian tradition would survive in Russia.

In fact, he declared, “It is here that we see the dawn of hope: for no matter how formidably Communism bristles with tanks and rockets, no matter what successes it attains in seizing the planet, it is doomed never to vanquish Christianity.”

From the depths of his own Christian faith, Solzhenitsyn rightly diagnoses the problem: it’s not some external force that makes evil occur; rather, it comes from within.

All attempts to find a way out of the plight of today’s world are fruitless unless we redirect our consciousness, in repentance, to the Creator of all: without this, no exit will be illumined, and we shall seek it in vain. . . .

We must first recognize the horror perpetrated not by some outside force, not by class or national enemies, but within each of us individually, and within every society. This is especially true of a free and highly developed society, for here in particular we have surely brought everything upon ourselves, of our own free will. We ourselves, in our daily unthinking selfishness, are pulling tight that noose.

Some might wonder why this sudden interest on my part in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, enough to warrant two posts this week. I give credit to a book I’m currently reading by Terry Glaspey, 75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know. Glaspey’s essay on Solzhenitsyn revived my remembrance of how he inspired me during the 1980s when I was reading Whittaker Chambers’s Witness (which conveys the same spirit as Solzhenitsyn’s writings).

Some might wonder why this sudden interest on my part in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, enough to warrant two posts this week. I give credit to a book I’m currently reading by Terry Glaspey, 75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know. Glaspey’s essay on Solzhenitsyn revived my remembrance of how he inspired me during the 1980s when I was reading Whittaker Chambers’s Witness (which conveys the same spirit as Solzhenitsyn’s writings).

I was also quite taken by a quote Glaspey included in his essay. When asked shortly before his death in 2008 what he thought about dying, Solzhenitsyn expressed confidence that it would be “a peaceful transition.” He concluded,

As a Christian, I believe there is life after death, and so I understand that this is not the end of life. The soul has a continuation, the soul lives on. Death is only a stage, some would even say a liberation. In any case, I have no fear of death.

May the writings and the character of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn continue to inspire us to be faithful to the truth.