I’ve never read any of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s novels. His Gulag Archipelago has been sitting on my bookshelf for a couple of decades at least. Yes, I’ve glanced at it a few times, but to my utter shame, I’ve not taken the time to digest it. My only excuse is the volume of other reading that has always been either more enticing or more needed at the time.

I’ve never read any of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s novels. His Gulag Archipelago has been sitting on my bookshelf for a couple of decades at least. Yes, I’ve glanced at it a few times, but to my utter shame, I’ve not taken the time to digest it. My only excuse is the volume of other reading that has always been either more enticing or more needed at the time.

I do plan to read it, fitting it in somewhere between Dante’s Divine Comedy and Plato’s Republic, among others.

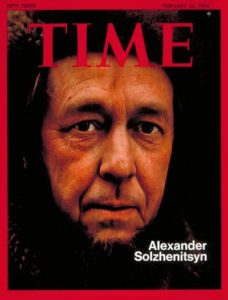

Yet this doesn’t mean I’m not familiar with Solzhenitsyn, the Russian author who suffered in that very gulag he wrote about, who was then internally exiled for a number of years, who had to sneak his writings out of the USSR, and whose brilliance was recognized in the West by the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970, and was then expelled from his native country for “treason” in 1974.

Solzhenitsyn lived in the US for many years during his expulsion, hibernating in small-town Vermont and rarely making public appearances. However, in 1978, he accepted an invitation to speak at Harvard’s commencement. The liberal intelligentsia didn’t know they were going to hear a speech about the spiritual vacuum of the West; they were appalled at his audacity. In fact, he was speaking truth.

I read that speech in the late 1980s and was deeply impressed by his willingness to say that hard things that needed to be said.

I read that speech in the late 1980s and was deeply impressed by his willingness to say that hard things that needed to be said.

His second paragraph offered a preview of what the audience could expect to hear that day:

Harvard’s motto is “VERITAS.” Many of you have already found out and others will find out in the course of their lives that truth eludes us as soon as our concentration begins to flag, all the while leaving the illusion that we are continuing to pursue it. This is the source of much discord. Also, truth seldom is sweet; it is almost invariably bitter. A measure of truth is included in my speech today, but I offer it as a friend, not as an adversary.

When Harvard first came up with that motto, it knew what truth was. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, it had departed from God’s truth. Solzhenitsyn was prescient when he noted that when we leave aside truth, we still have “the illusion that we are continuing to pursue it.” That’s the status of a typical university in our day.

He went on to make a statement that undoubtedly caused his audience to squirm, as it seemed to be aimed right at them:

A decline in courage may be the most striking feature that an outside observer notices in the West today. The Western world has lost its civic courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, in each government, in each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations.

Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling and intellectual elites, causing an impression of a loss of courage by the entire society. There are many courageous individuals, but they have no determining influence on public life.

This was in 1978. The statement rings true still today.

Governments were meant to serve man, Solzhenitsyn noted, and America embedded that concept in its Declaration of Independence, but the pursuit of happiness of the eighteenth century has now resulted in the welfare state and a debased meaning of “happiness.”

If Solzhenitsyn were alive today, he might be amazed how another of his warnings has become the norm for our society:

The defense of individual rights has reached such extremes as to make society as a whole defenseless against certain individuals. It is time, in the West, to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.

On the other hand, destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space. Society has turned out to have scarce defense against the abyss of human decadence, for example against the misuse of liberty for moral violence against young people, such as motion pictures full of pornography, crime, and horror.

This is all considered to be part of freedom and to be counterbalanced, in theory, by the young people’s right not to look and not to accept. Life organized legalistically has thus shown its inability to defend itself against the corrosion of evil.

From his decidedly Christian worldview, he asserted,

This tilt of freedom toward evil has come about gradually, but it evidently stems from a humanistic and benevolent concept according to which man—the master of the world—does not bear any evil within himself, and all the defects of life are caused by misguided social systems, which must therefore be corrected. Yet strangely enough, though the best social conditions have been achieved in the West, there still remains a great deal of crime.

In other words, man is sinful.

Solzhenitsyn wanted to make sure his audience did not misunderstand his critique:

I hope that no one present will suspect me of expressing my partial criticism of the Western system in order to suggest socialism as an alternative. No; with the experience of a country where socialism has been realized, I shall not speak for such an alternative.

What then, is to be done? The rest of his speech is replete with memorable phrases that I will attempt to offer here in a coherent, logical order:

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Delivering His Harvard Commencement Address

The forces of Evil have begun their decisive offensive. You can feel their pressure, yet your screens and publications are full of prescribed smiles and raised glasses. What is the joy about?

How has this unfavorable relation of forces come about? How did the West decline from its triumphal march to its present debility? . . .

In early democracies, as in American democracy at the time of its birth, all individual human rights were granted on the ground that man is God’s creature. That is, freedom was given to the individual conditionally, in the assumption of his constant religious responsibility. . . .

Subsequently, however, all such limitations were eroded everywhere in the West; a total emancipation occurred from the moral heritage of Christian centuries with their great reserves of mercy and sacrifice. . . .

Thus during the past centuries and especially in recent decades, as the process became more acute, the alignment of forces was as follows: Liberalism was inevitably pushed aside by radicalism, radicalism had to surrender to socialism, and socialism could not stand up to communism. . . .

I am not examining the case of a disaster brought on by a world war and the changes which it would produce in society. . . . Yet there is a disaster which is already very much with us. I am referring to the calamity of an autonomous, irreligious humanistic consciousness.

It has made man the measure of all things on earth—imperfect man, who is never free of pride, self-interest, envy, vanity, and dozens of other defects. . . .

We have placed too much hope in politics and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life.

There is so much more, but I will stop there. Read it all for yourself sometime. You can see why it was not enthusiastically received by the liberal elite. Yet it was truth delivered from the depths of personal experience.